08, 09, 10 - Input/Output, Secondary Storage, File Systems

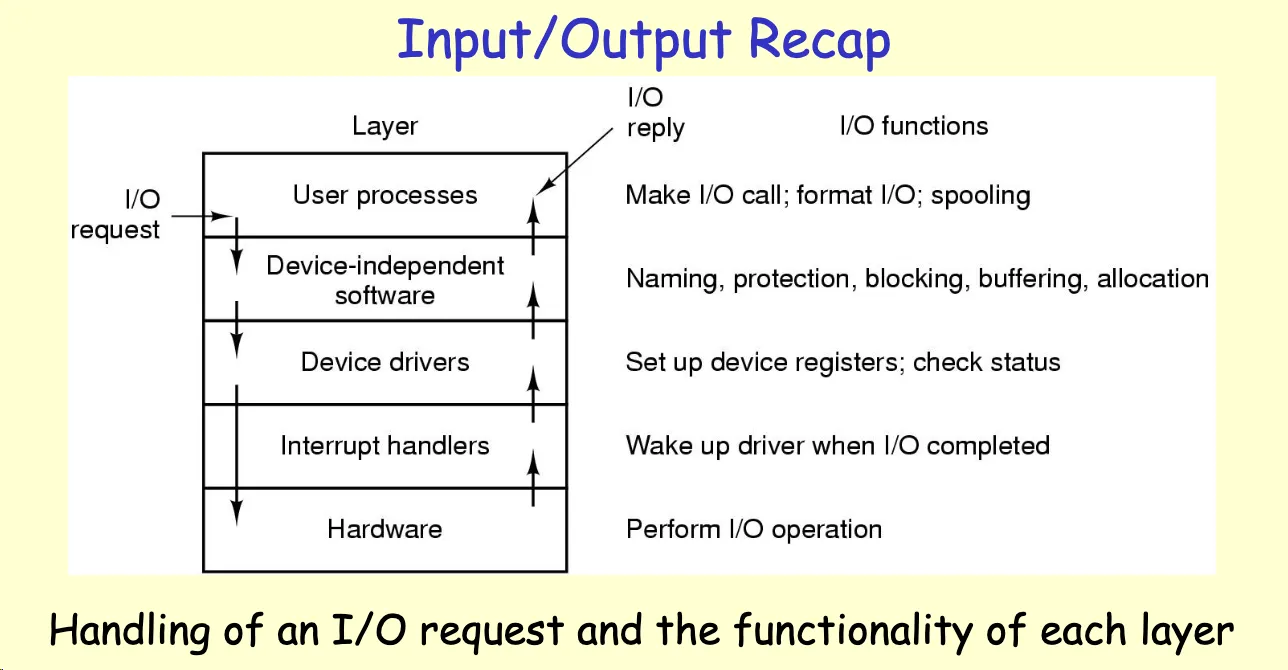

Problem 1: Life Cycle of an I/O Request

Describe in detail the life cycle of an I/O request such as “read”. That is, explain the entire set of steps taken from the time the user app issues the “read” system call until the system call returns with the data from the kernel. Assume that the I/O request completes successfully.

Student Solution

Answer by Lauren:

Problem 2: Device Drivers

What’s a device driver? Why is it necessary to implement a new device driver for each OS?

Student Solution

Answer by Lauren:

A device driver translates between the OS and device hardware. Every OS has its own APIs that drivers must use to interact correctly, so you need a driver to translate to that specific OS’s environment.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Device drivers are the critical bridge between operating systems and hardware. Understanding this relationship helps explain why driver support is often the limiting factor when adopting new operating systems.

What a Device Driver Does:

A device driver is a software module that acts as a translator and controller:

The driver converts:

- High-level OS commands → Device-specific hardware commands

- Hardware interrupts/status → OS-compatible events/callbacks

Example: Printing “Hello”

Application: printf("Hello");

↓

OS write() syscall

↓

Printer Driver receives: write 5 bytes

↓

Driver translates to printer protocol:

- Set paper size register

- Load font table

- Send character codes

- Monitor status registers

- Handle mechanical delays

↓

Physical Printer hardware executes

Why a New Driver Per OS?

Each OS has fundamentally different:

-

Device Access Model:

- Linux:

/dev/lp0(file interface) - Windows:

\\.\LPT1(device interface) - macOS: IOKit framework

- Linux:

-

Interrupt Handling:

- Linux: Uses IRQ numbers, tasklets

- Windows: Uses ISRs, DPCs

- Real-time OS: Preemption models differ

-

Memory Access Patterns:

- Linux: MMU with virtual addressing

- Embedded OS: Direct physical memory access

- NUMA systems: Multi-socket complexities

-

Concurrency Model:

- Single-threaded: Driver can be simpler

- Multi-threaded: Requires locking, atomic operations

- Kernel-level threads vs. user threads

-

API/Calling Conventions:

- Function signatures differ

- Error codes differ (Linux errno vs. Windows NTSTATUS)

- Power management interfaces completely different

Real-World Impact:

| Device | Linux | Windows | macOS |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA GPU | Separate drivers | Separate drivers | Separate drivers |

| WiFi Card | ath10k driver | Qualcomm driver | AppleWifi driver |

| Printer | CUPS + ppd | Windows Print Spooler | Apple Print System |

Each requires independent development, testing, and certification.

API Differences Example:

Linux (interrupt handler):

irqreturn_t handler(int irq, void *dev_id) {

// Hardware communication

return IRQ_HANDLED;

}

Windows (interrupt handler):

BOOLEAN InterruptHandler(PKINTERRUPT Interrupt, PVOID ServiceContext) {

// Hardware communication

return TRUE;

}

Why This Matters:

When a new OS is released or a new device is created:

- Driver source code for one OS cannot be ported directly to another

- Core logic might be 80% the same, but the OS interface layer (20%) is completely different

- Driver development typically takes months per OS

Vendors’ Solution:

- Hardware abstraction layers (HALs) reduce per-OS code

- Open standards (USB, PCIe, SATA) reduce driver complexity

- Driver frameworks (Windows WDF, Linux driver framework) provide templates

- POSIX standards help minimize differences between Unix-like OSes

Key Insight:

Device drivers are why hardware doesn’t automatically “just work” on a new OS. The driver is where hardware meets OS philosophy—and those philosophies are fundamentally different.

Problem 3: Linux I/O Device Classification

Briefly explain how Linux classifies all I/O devices. Give one example of an I/O device under each category.

Student Solution

Answer by Lauren:

Character devices: Anything that’s a bytestream of characters (e.g., printers, keyboards, mice)

Block devices: Disks that store information in fixed-sized addressed blocks

Network devices: NICs like Ethernet and WiFi adapters that can deliver or accept TCP/IP packets

Elaboration (by LLM):

Linux’s device classification is elegant because it maps the fundamental I/O abstraction to different hardware characteristics. Understanding this helps explain why different devices need different system calls and interfaces.

Why This Classification Matters:

The three categories reflect how each device fundamentally differs in how data flows and is accessed.

Character Devices (Stream-Based):

Data flows as an endless sequence of characters with no fixed positions:

Keyboard: a b c a a → [handler] → Application receives: aaaa

Properties:

- No fixed addressing (can’t ask for “byte at position 1000”)

- Sequential access only

- Variable-length transfers

- Often interactive (waiting for human input)

Examples:

/dev/tty*– Terminal/console/dev/lp0– Printer/dev/null– Null device (discards all data)/dev/random– Random number generator/dev/zero– Infinite stream of zeros

Key Characteristic: Once you read a byte, it’s gone.

Block Devices (Position-Based):

Data is organized in fixed-size blocks with specific addresses:

Disk: [Block 0: 512B] [Block 1: 512B] [Block 2: 512B] ...

Request: "Give me block #42"

Properties:

- Random access – can request any block

- Fixed block size – typically 512B, 4KB, or 8KB

- Persistent – read the same block again, get same data

- Seekable – can access blocks in any order

Examples:

/dev/sda,/dev/sdb– Hard drives/dev/nvme0– NVMe SSD/dev/mmcblk0– SD card/dev/loop0– Loopback device

Key Characteristic: Can seek to any position and read/write repeatedly.

Network Devices (Packet-Based):

Data flows as discrete packets over network protocols:

Network: [Packet 1: 1500B] [Packet 2: 1500B] [Packet 3: 512B]

Ethernet frame → IP datagram → TCP segment

Properties:

- Packet-oriented – discrete units, not streams

- Bidirectional – send and receive

- Protocol-driven – follow TCP/IP, UDP, etc.

- Remote – data crosses networks

Examples:

/dev/eth0,/dev/eth1– Ethernet interfaces/dev/wlan0– WiFi interfaces/dev/tun*– VPN tunnels

Key Characteristic: Packets, not bytes; protocol-aware.

How Linux Uses This Classification:

| Aspect | Character | Block | Network |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syscalls | read(), write() | read(), write(), lseek() | send(), recv(), select() |

| Buffering | Unbuffered usually | Heavily buffered | Buffered with TCP windows |

| Addressing | Sequential only | Random access | Address = IP+port |

| Driver API | TTY layer, misc | Block I/O layer | Network stack |

Why This Design?

Instead of “one interface for all devices,” Linux provides specialized interfaces matching each device type:

- No seeking on keyboard? Character interface doesn’t support it

- Packets on network? Use network syscalls optimized for packets

- Random block access? Block interface is optimized for this

Practical Example: Why It Matters

# Character device (sequential)

$ cat /dev/urandom | head -c 10

# Works: reads sequentially until 10 bytes

# Block device (random access)

$ dd if=/dev/sda bs=512 skip=1000 count=1

# Works: seeks to block 1000, reads 1 block

# Can you seek on keyboard?

$ dd if=/dev/stdin bs=1 skip=1000 count=1

# Mostly fails: keyboard is sequentialKey Insight:

This classification isn’t arbitrary—it maps directly to hardware realities. Character devices are serial in nature, block devices support random access, and network devices operate at the protocol level. Knowing which type your device is tells you exactly what operations are possible and efficient.

Problem 4: Device Naming in Linux vs Windows

How does Linux “name” I/O devices? Is it different than Windows? If so, how?

LLM Solution

Linux names I/O devices in the /dev directory using descriptive names based on device type and number. For example: /dev/sda (first disk detected), /dev/sdb (second disk detected), /dev/sdc (third disk detected), etc. Each disk—whether internal, USB drive, or external hard drive—gets the next available device name in sequence based on the order it’s detected by the system. Other examples include: /dev/tty0 (terminal), /dev/eth0 (first network interface), /dev/null (null device), etc.

Windows uses a different approach with drive letters (like C: and D:) for storage devices and UNC paths for network resources, rather than a unified /dev directory structure.

Problem 5: I/O Call Semantics in Linux

Briefly explain the I/O call semantics available in Linux. If you have a single threaded application but multiple file descriptors to read from, which I/O call semantic makes more sense? Would your answer change if you have a multi-threaded application?

LLM Solution

I/O Call Semantics Available in Linux:

Linux provides several I/O semantics:

- Blocking I/O: The call blocks until data is available or the operation completes

- Non-blocking I/O: The call returns immediately even if data is not available

- Multiplexing: Using

select(),poll(), orepoll()to monitor multiple file descriptors simultaneously

For a single-threaded application with multiple file descriptors:

Non-blocking I/O or multiplexing (via select(), poll(), or epoll()) makes more sense. Blocking I/O would cause the thread to get stuck waiting on one descriptor while others have data ready.

For a multi-threaded application:

Blocking I/O would be the simpler option with less overhead. Different threads can block on different file descriptors simultaneously, allowing the application to handle multiple I/O sources concurrently without the complexity of non-blocking calls or multiplexing.

Problem 6: Device Independent Software Layer Functions

List 4 functions of the Device Independent Software layer.

Student Solution

Answer by Lauren:

- Scheduling: I/O request queues

- Buffering: Storing data in memory while transferring between devices

- Caching: Fast memory holding copy of data

- Process I/O state: Kernel keeps state information for processes (open files, network connections, etc.)

Elaboration (by LLM):

The Device Independent Software layer is the OS’s abstraction boundary—it hides hardware complexity while providing unified services to applications. Think of it as “what the OS guarantees” independent of which specific device you’re using.

1. Scheduling: I/O Request Queues

When multiple processes want I/O, requests can’t all happen simultaneously. The OS queues them:

Application 1: read from disk

Application 2: write to disk

Application 3: read from network

↓

[OS Scheduler]

↓

Queue: [App1 read] → [App3 read] → [App2 write]

Order optimized by disk scheduling algorithm (SCAN, LOOK, FCFS)

Why it matters:

- Prevents I/O chaos (all devices screaming at once)

- Optimizes order (can reorder disk requests to minimize head movement)

- Ensures fairness (prevents process starvation)

Example: SCAN algorithm might reorder disk requests to sweep across tracks instead of thrashing back and forth.

2. Buffering: Memory-Based Staging

Data is temporarily held in RAM during transfers:

Slow Disk (ms scale) → [RAM Buffer] → Fast App (ns scale)

(staging area)

Why it matters:

- Speed mismatch: Disk reads in 5-10ms, but app wants data in microseconds

- Decouples producer/consumer: Disk keeps filling buffer while app drains it

- Allows partial transfers: Can read disk sector-by-sector into buffer

Example: Line Buffering

printf("x"); // Writes to 1KB buffer (fast)

printf("y"); // Adds to buffer (fast)

printf("z"); // Adds to buffer (fast)

fflush(); // ONE system call sends all 3 bytes (efficient)Without buffering: 3 system calls. With buffering: 1 system call. 3× improvement!

3. Caching: Smart Memory Reuse

The OS keeps “hot” data in fast RAM instead of re-reading from slow disk:

First access: /home/user/file.txt → [Disk read: 5ms] → RAM cache

Second access: /home/user/file.txt → [Cache hit: 0.1μs] ← 50,000× faster!

Why it matters:

- Most programs reuse recent data (temporal locality)

- Cache hits are nearly free (nanoseconds vs. milliseconds)

- Dramatically improves performance for repeated access

Example:

$ time cat file.txt # First time: 100ms (disk read)

$ time cat file.txt # Second time: 1ms (cache hit)Real-world: OS caches 30-50% of RAM for frequently accessed files.

4. Process I/O State: Bookkeeping

OS maintains state for each process’s I/O:

Process A:

- File descriptor 3 → /home/user/data.txt (opened for reading)

- Current file position: byte 1024

- Outstanding I/O: 1 pending read request

- Buffered data: 256 bytes waiting in buffer

Process B:

- File descriptor 7 → /dev/sda (disk device)

- Current position: sector 50000

- Outstanding I/O: 3 pending requests

- Error state: none

Why it matters:

- Tracks which files processes have open

- Maintains file positions (so each process has independent “file pointer”)

- Remembers pending I/O (what’s in flight)

- Enables proper cleanup (close all files on process exit)

How They Work Together:

Key Insight:

All four functions work together to hide the messy reality of hardware from applications. Without them:

- Apps would deadlock waiting for I/O

- Every duplicate read would hit slow disk

- Files couldn’t have independent positions per process

- System would be chaotic and slow

The Device Independent layer is “what makes the OS an OS”—not just passing requests through, but intelligently managing them.

Problem 7: High-level I/O Libraries vs System Calls

Given that the OS already provides “read” and “write” system calls to read from/write to an I/O device, why do most programmers still prefer using a high-level I/O library to perform I/O? Briefly explain.

Student Solution

Answer by Lauren:

High-level I/O libraries help to format I/O (like printf) and also buffer data before making system calls to improve performance. This reduces the overhead of frequent system calls and provides more convenient functionality.

Elaboration (by LLM):

This gets at a fundamental systems design principle: system calls are expensive, so minimize them. Understanding why requires looking at the cost of crossing the user-kernel boundary.

The Cost of System Calls

System calls switch CPU from user mode to kernel mode—a context switch with significant overhead:

Direct Hardware Access: 1 ns

Read from L1 cache: 0.5 ns

Read from RAM: 100 ns

System call: 1,000-10,000 ns ← Why? See below

Why System Calls Are Expensive (Simplified):

- Context switch (save/restore registers, memory state): ~1,000 ns

- Permission checks (is this process allowed?): ~100 ns

- Mode transition (kernel mode vs. user mode): ~500 ns

- Cache invalidation (security: clear sensitive data): ~500 ns

- Return to user mode (restore state): ~500 ns

Total: ~3,000-5,000 ns per system call

The Problem Without Buffering

// Bad: Direct system calls

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

write(fd, "x", 1); // 1 char = 1 syscall

}

// Cost: 100 syscalls × 5,000 ns = 500,000 ns = 0.5 msThe Solution: Buffering

// Good: Buffered I/O

char buffer[1024];

int pos = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

buffer[pos++] = 'x';

if (pos >= 1024) {

write(fd, buffer, 1024); // 1 syscall for 1024 chars

pos = 0;

}

}

// Cost: 1 syscall × 5,000 ns ≈ 0.005 ms ← 100× faster!Real-World Example: printf

// Without buffering (hypothetical direct syscalls)

printf("a"); // syscall

printf("b"); // syscall

printf("c"); // syscall

// Cost: 3 syscalls

// With standard buffering (typical case)

printf("a"); // buffered

printf("b"); // buffered

printf("c"); // buffered

printf("\n"); // Forces flush, 1 syscall

// Cost: 1 syscall ← 3× improvementFormatting Benefits

Beyond performance, high-level libraries provide convenience:

// What you write:

printf("User %d logged in at %s", user_id, time_str);

// What the system call library does:

// 1. Format the string ("%d" → convert int to string, etc.)

// 2. Build output: "User 42 logged in at 14:30:00"

// 3. Buffer it

// 4. Maybe flush if full or newline encountered

// 5. Call write() syscall once

// Equivalent with raw syscalls would be:

char buffer[256];

sprintf(buffer, "User %d logged in at %s", user_id, time_str);

write(fd, buffer, strlen(buffer));

// Much more tedious!Why Not Just Use System Calls?

| Approach | Performance | Code Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Direct syscalls | Slow (many calls) | Simple but tedious |

| Buffered library | Fast (batched calls) | Convenient, automatic |

| Manual buffering | Fast (batched calls) | Complex, error-prone |

The Buffering Trade-offs

Advantage: 10-100× performance improvement Disadvantage: Data sits in buffer until flushed (latency)

printf("Processing..."); // Buffered, not yet written

// User sees nothing until buffer fills or \n arrives

fflush(stdout); // Force write, user sees text immediatelyWhen Buffering Matters

- Text output: Buffered by default (line buffering)

- Binary files: Often fully buffered (larger buffer)

- Interactive: Line buffering (flush on newline)

- Pipes: Fully buffered (no newlines to trigger flush)

Example: Why Interactive Programs Need Line Buffering

# Line-buffered output (default for terminals)

$ ./program

Please enter name: [user waits here—prompt visible]

# Fully buffered output (if stdout is piped)

$ ./program | cat

[nothing visible until buffer fills, user confused!]Modern Complications

Modern systems add more layers:

- Application buffering (your code)

- libc buffering (C library)

- Kernel buffering (page cache)

- Disk controller buffering (hardware cache)

Each layer trades latency for throughput.

Key Insight:

System calls are the “expensive bridge” between user programs and kernel services. Any chance to cross the bridge fewer times is worth it. This is why buffering is ubiquitous—it’s one of the simplest, most effective performance optimizations in systems.

This principle extends beyond I/O:

- Batching: collect operations, execute once

- Coalescing: combine multiple requests into one

- Queuing: accumulate work, process in bulk

All are variations on “fewer expensive transitions = better performance.”

Problem 8: Cylinder Definition in Disks

What’s is a cylinder (as it applies to disks). Briefly explain.

LLM Solution

Cylinder Definition:

A cylinder in disk terminology is the set of tracks with the same track number on all surfaces (platters) of a multi-platter hard disk.

Physical Structure:

In a hard disk with multiple spinning platters and read/write heads:

- Each platter has concentric circular tracks (like rings on a tree)

- Each head reads/writes from one track on one platter

- When all heads are positioned at the same distance from the center, they form a cylinder

Example with 3 Platters:

Platter 1: Track 100 ←─┐

Platter 2: Track 100 ←─┼─ Cylinder 100

Platter 3: Track 100 ←─┘

Platter 1: Track 101 ←─┐

Platter 2: Track 101 ←─┼─ Cylinder 101

Platter 3: Track 101 ←─┘

Why Cylinders Matter:

- Seek Time Reduction: All heads move together. Once heads reach a cylinder, all tracks in that cylinder can be accessed without additional head movement

- Performance: Accessing all data in a cylinder is fastest since only one seek is needed

- Disk Scheduling: Many scheduling algorithms (SCAN, C-SCAN) minimize head movement by accessing cylinders sequentially

Advantages of Cylinder Access:

- Data layout can take advantage of cylinder structure

- Minimize expensive mechanical head positioning

Problem 9: Rotational Latency

What’s rotational latency (as it applies to disks). Briefly explain.

LLM Solution

Rotational Latency Definition:

Rotational latency (also called rotational delay) is the time it takes for the desired sector of a rotating disk platter to move under the read/write head after the head has been positioned over the correct track.

Components of Disk Access Time:

Total Access Time = Seek Time + Rotational Latency + Transfer Time

Example with 7200 RPM disk:

- Seek time: 5 ms (head movement)

- Rotational latency: 0-4.17 ms (sector positioning)

- Transfer time: 0.1 ms (reading data)

How Rotational Latency Works:

- Head positions at correct track (seek time passes)

- Disk continues rotating

- Desired sector gradually moves under the head

- When sector arrives, reading/writing begins

Average Rotational Latency:

In worst case, need to wait full rotation. Average = half rotation:

For 7200 RPM: Rotation time = 60/7200 = 8.33 ms Average latency = 8.33/2 = 4.17 ms

Key Points:

- Unavoidable for mechanical disks (sectors don’t move instantly)

- Depends on disk rotation speed (RPM)

- Average = 50% of one full rotation

- Faster rotating disks have lower rotational latency

- Cannot be eliminated, only minimized by increasing RPM

Problem 10: Average Rotational Latency at 7200 RPM

What’s the average rotational latency for a disk that rotates at 7200rpm?

LLM Solution

Calculation:

RPM = 7200 revolutions per minute

Step 1: Convert to rotations per second

Rotations per second = 7200 / 60 = 120 revolutions/second

Step 2: Calculate time for one full rotation

Time for one rotation = 1 / 120 = 0.00833 seconds = 8.33 milliseconds

Step 3: Calculate average rotational latency

Average = (1/2) × rotation time = 0.5 × 8.33 ms = 4.17 ms

Explanation:

Average rotational latency is half of one full rotation because:

- Best case: Desired sector is already under the head (0 ms wait)

- Worst case: Desired sector just passed the head (full rotation needed = 8.33 ms)

- Average: Half the disk must rotate on average = 4.17 ms

Answer: 4.17 milliseconds (or approximately 4.2 ms)

Problem 11: Seek Time in Disks

What’s seek time (as it applies to disk)? Briefly explain.

LLM Solution

Seek Time Definition:

Seek time is the time required for the read/write head of a hard disk to move from its current position to a new track where data is located.

Physical Process:

- Current head position: Track X

- Requested data on: Track Y

- Head moves radially inward or outward

- Seeks to correct track Y

- Stabilizes and begins reading/writing

Seek Time Components:

Total Seek Time = Start time + Acceleration + Travel + Deceleration + Settling time

Typical seek time: 2-15 milliseconds (depends on distance)

Average seek time: ~5-7 milliseconds (for random access)

Factors Affecting Seek Time:

- Distance: Longer distance = longer seek time

- Track density: More tightly packed tracks = potentially longer seek

- Head mechanics: Acceleration/deceleration capabilities

- Settling time: Time for head to stabilize on target track

Example with 7200 RPM disk:

Minimum seek (adjacent track): ~0.5 ms

Full seek (track 0 to last track): ~14 ms

Average seek: ~7 ms (for random access across disk)

Why Seek Time Matters:

- Major component of total disk access time

- Total Access = Seek + Rotational Latency + Transfer

- Seeking is the slowest component of disk I/O

- Disk scheduling algorithms focus on minimizing total seek time

Problem 12: SSDs vs Hard Disks

Briefly explain the pros and cons of using Non-Volatile Memory (SSDs) compared to hard disks (HDDs)?

LLM Solution

Solid State Drives (SSDs) vs Hard Disk Drives (HDDs):

| Aspect | SSDs | HDDs |

|---|---|---|

| Speed | ✅ Much faster (100-550 MB/s) | Slower (100-200 MB/s) |

| Seek Time | ✅ Minimal (<1 ms) | Significant (5-10 ms) |

| Power | ✅ Lower power consumption | Higher power (moving parts) |

| Noise | ✅ Silent (no moving parts) | Audible (mechanical) |

| Durability | ✅ No moving parts (more robust) | Mechanical failure risk |

| Cost | ❌ Expensive per GB | ✅ Cheaper per GB |

| Capacity | ❌ Limited (1-8 TB common) | ✅ Larger (2-20+ TB) |

| Lifespan | ❌ Limited write cycles (wear out) | ✅ Longer lifespan (mechanical wear) |

| Write Amplification | ❌ 2-10x overhead | ✅ 1x (direct write) |

| Fragmentation | ✅ No impact on speed | ❌ Degrades performance |

Advantages of SSDs:

- Performance: 10-100x faster than HDDs for random access

- Reliability: No mechanical failure risk from drops/vibration

- Energy: Lower power consumption (mobile devices)

- Noise: Silent operation

- Responsiveness: Superior system responsiveness

Disadvantages of SSDs:

- Cost: 5-10x more expensive per gigabyte

- Capacity: Maximum size smaller than HDDs

- Write Endurance: Limited write cycles (100,000-1,000,000)

- Wear Leveling: Complex firmware needed

- Full Drive: Performance degrades when full

- Write Amplification: Physical writes exceed logical writes (firmware overhead)

Disadvantages of HDDs:

- Speed: Much slower random access

- Mechanical Issues: Moving parts can fail

- Noise: Audible operation

- Power: Higher consumption

- Fragmentation: Impacts performance significantly

Best Use Cases:

SSDs: OS drives, databases, performance-critical applications, laptops, mobile devices

HDDs: Large-capacity storage, archival data, backup systems, cost-sensitive applications

Current Trend: SSDs for primary storage, HDDs for secondary/backup storage (hybrid approach)

Problem 13: SSD Physical Structure

Briefly describe the physical structure of an SSD. That is, what is a page, what is a block as they apply to SSDs. How does an SSD perform the “modify” operation?

LLM Solution

SSD Physical Structure:

Basic Components:

SSDs use NAND flash memory organized in a hierarchical structure:

SSD Memory Hierarchy:

Flash Memory Array

├── Die (4-8 dies per package)

│ ├── Plane (2-4 planes per die)

│ │ ├── Block (128-512 MB per block)

│ │ │ ├── Page (4-16 KB per page)

│ │ │ ├── Page

│ │ │ └── ...

│ │ ├── Block

│ │ └── ...

Page:

- Smallest readable/writable unit (4 KB - 16 KB typical)

- Can be read and written

- Multiple pages per block

- Basic unit for data access

Block:

- Smallest erasable unit (128 KB - 4 MB typical)

- Contains 128-256 pages

- Must erase entire block before rewriting

- This asymmetry causes “write amplification”

The Modify Problem:

Unlike HDDs, SSDs cannot directly overwrite data. Modifying a page requires:

Traditional Approach (Inefficient):

1. Mark old page as invalid

2. Write new page to empty page

3. Erase old block (if empty)

This causes write amplification (writing more than necessary).

SSD Modify Operation:

Original Block:

┌─────────────────────────────────┐

│ Page 0: [Valid data] │

│ Page 1: [Data to modify] │ Read

│ Page 2: [Valid data] │

│ ... │

└─────────────────────────────────┘

↓

Read entire block into buffer

↓

Modify target page in buffer

↓

Write modified block to new location

↓

Mark original block for garbage collection

↓

┌─────────────────────────────────┐

│ Page 0: [Valid data] │

│ Page 1: [Modified data] ← New │ Write

│ Page 2: [Valid data] │

│ Page 3: [Empty] │

│ ... │

└─────────────────────────────────┘

Key Points:

- Read: Entire block must be read from NAND flash

- Modify: Change target page in RAM buffer

- Write: Entire modified block written to new location

- Erase: Old block marked for garbage collection, erased later

- Result: All pages in block rewritten (write amplification)

Write Amplification Factor (WAF):

If modifying 1 page requires rewriting entire block of 256 pages:

- WAF = 256:1 (256 physical writes for 1 logical write)

- Actually: WAF = 2-10 in practice due to optimization

Problem 14: Flash Translation Layer in SSDs

What’s the purpose of the Flash Translation Layer (FTL) in SSDs? How does the SSD update the FTL during garbage collection?

LLM Solution

Flash Translation Layer (FTL) Purpose:

The FTL is firmware that manages the SSD at a low level. It acts as an intermediary between the operating system and raw flash memory.

Key Responsibilities:

-

Logical to Physical Address Mapping

- Maps logical block addresses (LBAs) from OS to physical NAND locations

- OS thinks it’s writing to sequential locations (LBA 0, 1, 2, …)

- FTL translates to actual NAND blocks (scattered locations)

- Hides wear-out patterns from OS

-

Wear Leveling

- Distributes writes evenly across all NAND blocks

- Prevents some blocks from wearing out faster

- Extends SSD lifespan

-

Bad Block Management

- Tracks and avoids defective blocks

- Reallocates to good blocks

-

Garbage Collection

- Reclaims space from invalidated pages

- Erases empty blocks

- Manages invalid page lists

FTL Structure:

┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Mapping Table (FTL) │

├─────────────────┬─────────────────┤

│ Logical Address │ Physical Address│

├─────────────────┼─────────────────┤

│ LBA 0 │ Block 47, Page 3│

│ LBA 1 │ Block 12, Page 8│

│ LBA 2 │ Block 89, Page 0│

│ ... │ ... │

└─────────────────┴─────────────────┘

FTL Update During Garbage Collection:

Scenario: Block 47 has invalid pages, needs garbage collection

Step 1: Identify Block for Garbage Collection

┌─────────────────────────────────┐

│ Block 47 (Candidate) │

├─────────────────────────────────┤

│ Page 0: Invalid ❌ │

│ Page 1: Invalid ❌ │

│ Page 2: Valid (LBA 100) ✅ │

│ Page 3: Valid (LBA 0) ✅ │

│ ... │

└─────────────────────────────────┘

Step 2: Read Valid Pages into Buffer

┌──────────────────┐

│ Buffer │

├──────────────────┤

│ LBA 100 data │

│ LBA 0 data │

└──────────────────┘

Step 3: Write Valid Pages to New Block

┌─────────────────────────────────┐

│ Block 55 (New, Empty) │

├─────────────────────────────────┤

│ Page 0: LBA 100 data │

│ Page 1: LBA 0 data │

│ Page 2-255: Empty │

└─────────────────────────────────┘

Step 4: Update FTL Mapping Table

OLD Mapping:

│ LBA 100 → Block 47, Page 2 │

│ LBA 0 → Block 47, Page 3 │

NEW Mapping:

│ LBA 100 → Block 55, Page 0 │ ← Updated

│ LBA 0 → Block 55, Page 1 │ ← Updated

Step 5: Mark Old Block for Erasure

Block 47: Mark as "Free" (all pages invalid now)

Schedule for erase operation

After erase: Available for new writes

Step 6: Update Valid Page Counts

Block 47: Valid pages: 2 → 0 (mark for erase)

Block 55: Valid pages: 0 → 2 (new data)

FTL Optimization:

- Lazy Erase: Don’t erase immediately; queue for background erase

- Batch Updates: Group FTL updates to reduce overhead

- Incremental GC: Collect one block at a time vs. all blocks

- Hotness Tracking: Separate hot/cold data to reduce GC impact

Implications:

- FTL adds firmware overhead but essential for performance

- Complex mapping table requires significant RAM

- GC can cause write amplification (excessive NAND writes)

- GC operations may cause latency spikes

Problem 15: TRIM Command

Briefly describe the role of the TRIM command sent from the OS to an SSD.

LLM Solution

TRIM Command Purpose:

The TRIM command allows the operating system to inform the SSD which data blocks are no longer needed, enabling the SSD firmware to proactively manage garbage collection and maintain performance.

Why TRIM is Needed:

Without TRIM:

File System Level: SSD FTL Level:

┌──────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────┐

│ File deleted │ │ Pages marked │

│ from directory │ │ "valid" still │

│ (OS think it's │ │ │

│ gone) │ ╳ │ SSD doesn't know │

│ │ │ data is no longer│

│ │ │ needed! │

└──────────────────┘ └──────────────────┘

Result: SSD keeps "invalid" data until overwritten

Wastes space, impacts GC performance

With TRIM:

File System Level: SSD FTL Level:

┌──────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────┐

│ File deleted │ │ Pages marked │

│ from directory │ │ "invalid" │

│ │ │ │

│ TRIM command: │ ✅ │ SSD knows data │

│ "Blocks X-Y │──────────→ │ can be garbage │

│ are no longer │ │ collected! │

│ needed" │ │ │

└──────────────────┘ └──────────────────┘

Result: SSD can immediately reclaim space

Better GC planning

Improved long-term performance

TRIM Operations:

- OS sends TRIM command specifying LBAs (logical block addresses) of deleted data

- SSD FTL marks pages as invalid (not waiting for overwrite)

- Garbage collection can immediately use these blocks

- Performance maintained - avoid write amplification

Performance Impact:

Without TRIM (SSD fills up):

Days 1-5: Fast performance (lots of free space)

Days 10-15: Slower performance (less free space for GC)

Days 20+: Very slow (FTL must work harder)

With TRIM (enabled on Windows/Linux):

Days 1-5: Fast performance

Days 10-15: Fast performance (space maintained)

Days 20+: Fast performance (maintained)

TRIM Support:

- Operating Systems: Windows Vista+, Linux kernel 2.6.33+, macOS 10.6.8+

- File Systems: NTFS, ext4, APFS, HFS+

- SSDs: Most modern SSDs support TRIM

- Command:

fstrim(Linux), automatic (Windows, macOS)

Historical Note:

Before TRIM, SSDs experienced significant performance degradation over time as deleted blocks couldn’t be distinguished from valid data. TRIM was crucial for making SSDs practical for consumer use.

Problem 16: Write Leveling in SSDs

What’s “write leveling” as it applies to SSDs and why is it needed?

LLM Solution

Write Leveling (Wear Leveling) Definition:

Write leveling is a technique used by SSD firmware to distribute write/erase operations evenly across all NAND flash blocks to prevent premature wear-out of specific blocks.

Why Write Leveling is Needed:

NAND flash cells have a finite number of write/erase cycles before they fail:

- Typical endurance: 10,000 - 1,000,000 cycles per cell

- Different blocks wear at different rates if writes are concentrated

Problem Without Wear Leveling:

SSD with Naive Write Strategy:

Block 0: [Written 500,000 times] ← WORN OUT!

Block 1: [Written 500,000 times] ← WORN OUT!

Block 2: [Written 2,000 times] ← Fresh

Block 3: [Written 1,500 times] ← Fresh

Block 4: [Written 2,100 times] ← Fresh

...

Result: Blocks 0-1 fail after 1 year

Blocks 2-4 still have 99% lifespan left

SSD dies prematurely!

Solution With Wear Leveling:

SSD with Write Leveling Enabled:

Block 0: [Written 100,000 times] ← Balanced

Block 1: [Written 101,000 times] ← Balanced

Block 2: [Written 99,500 times] ← Balanced

Block 3: [Written 100,200 times] ← Balanced

Block 4: [Written 100,800 times] ← Balanced

...

Result: All blocks wear evenly

SSD lasts full rated lifespan

How Wear Leveling Works:

-

Track Block Age: FTL maintains counter for write cycles per block

-

Dynamic Data Movement:

- When hot data (frequently written) exists on old block

- Move it to younger block to balance wear

- Update FTL mapping table

-

Static Data Rotation:

- Even static (rarely written) data gets moved periodically

- Prevents some blocks from staying fresh

-

Wear Counter Update:

When writing to Block X: wear_count[X] += 1 If wear_count[X] is significantly higher than average: - Move fresh data to Block X - Move old data to younger blocks

Example:

Block Age: 0-100,000 writes

Initial:

Block 0: [Hot data, 95,000 writes] ← Nearly worn out

Block 1: [Cold data, 5,000 writes] ← Very fresh

After Wear Leveling:

Block 0: [Cold data, 95,000 writes] ← Stop using for writes

Block 1: [Hot data, 5,000 writes] ← Can handle more writes

Result: Extends life of both blocks

Techniques:

-

Dynamic Wear Leveling:

- Only moves hot data when wear discrepancy detected

- Lower overhead, less GC activity

-

Static Wear Leveling:

- Periodically redistributes all data

- More balanced wear, more overhead

-

Hybrid Wear Leveling:

- Dynamic for hot data + periodic static rotations

- Best balance for performance and longevity

Performance Implications:

- Background Operations: GC + wear leveling run during idle time

- Write Amplification: Extra moves increase physical writes

- Lifespan Trade-off: Better longevity requires slightly slower writes

- OS Support: TRIM helps by freeing space, reducing data movement

Example Lifespan Impact:

Without wear leveling: 2-3 years (early failure)

With wear leveling: 5-10 years (rated spec)

Problem 17: Device Independent Layer vs File System

Given that the device independent layer allows a disk to be read in blocks, why is it still necessary to implement a file system?

LLM Solution

What the Device Independent Layer Provides:

The device independent layer (or block I/O layer) allows:

- Reading/writing fixed-size blocks (512B - 4KB)

- Block-level abstraction over raw disk hardware

- Buffering, caching, disk scheduling

Why This Isn’t Enough - File System Necessity:

The device layer only handles where data goes physically; it doesn’t handle how users organize their data.

Problem Without File System:

User wants to:

1. Create a file "document.txt"

2. Store it somewhere on disk

3. Retrieve it later by name

4. Know how much space used

5. Prevent unauthorized access

Device layer can only do:

- Write block 512 to disk ✅

- Read block 512 from disk ✅

- But WHERE is my file? ❌

- WHAT data is mine? ❌

- HOW do I find "document.txt"? ❌

File System Responsibilities (Beyond Block Layer):

| Function | Device Layer | File System |

|---|---|---|

| Read/write blocks | ✅ | (uses device layer) |

| Organize data logically | ❌ | ✅ |

| Name-based access | ❌ | ✅ |

| Directory hierarchy | ❌ | ✅ |

| File metadata (size, permissions) | ❌ | ✅ |

| Space allocation | ❌ | ✅ |

| Access control | ❌ | ✅ |

| Free space management | ❌ | ✅ |

File System Layers:

┌─────────────────────────────────┐

│ User Application │ "Save document.txt"

├─────────────────────────────────┤

│ File System (ext4, NTFS, APFS) │ Maps filename → blocks

├─────────────────────────────────┤

│ Device Independent Layer (VFS) │ Read/write blocks

├─────────────────────────────────┤

│ Device Drivers │ Hardware-specific

├─────────────────────────────────┤

│ Physical Disk Hardware │ Raw NAND/magnetism

└─────────────────────────────────┘

Example: Writing a File

Without File System (raw blocks only):

User: "Save this 5KB file"

System: "I can write blocks to disk, but:

- Which blocks? (1000-1003 available, but what about other files?)

- How to find it later?

- How to prevent accidental overwrite?

→ Chaos!"

With File System:

User: "Save to document.txt"

FS: 1. Allocate blocks (1000-1003) for this file

2. Create inode with metadata

3. Create directory entry mapping "document.txt" → inode

4. Update bitmap of free blocks

5. Write data blocks using device layer

6. Track file size (5KB), permissions, dates

→ Organized and manageable!

Why File System is Essential:

- Naming: Users think in terms of filenames, not block numbers

- Organization: Hierarchical directories organize files logically

- Metadata: Permissions, timestamps, file size

- Allocation: Which blocks belong to which file?

- Sharing: Multiple users, multiple files without conflicts

- Durability: Recovery from crashes

Analogy:

Device Layer: Like storage bins with numbers (Bin 1, Bin 2, ...)

File System: Like a postal delivery system with addresses and names

Maps "123 Main St" → Bin 47

Without postal system, you can store things in bins, but finding them later is impossible.

Problem 18: Shortest Seek Time First Scheduling

Assume that the disk head is currently over cylinder 20 and you have disk requests for the following cylinders: 35, 22, 15, 55, 72, 8. In what order would you serve these requests if you were to employ Shortest Seek Time First (SSTF) scheduling algorithm?

Problem 19: C-SCAN Disk Scheduling

Suppose that a disk drive has 5000 cylinders, numbered 0 to 4999. The drive is currently serving a request at cylinder 143, and the previous request was at cylinder 125. The queue of pending requests, in FIFO order, is 86, 1470, 913, 1774, 948, 1509, 1022, 1750, 130. In what order would you serve these requests if you were to employ C-SCAN scheduling algorithm.

Problem 20: Disk Scheduling Algorithms

Assume that the disk request queue consists of the following disk requests each specified by the cylinder number: 111, 97, 123, 90, 102. Further assume that the disk arm is currently located over cylinder number 100. In what order would the requests be scheduled by this File System if the File System employs:

(a) First Come First Served (FCFS) policy?

(b) Shortest Seek Time First (SSTF) policy?

(c) SCAN policy? Assume the disk head is moving towards increasing cylinder numbers.

(d) C-SCAN policy? Assume the disk head is moving towards increasing cylinder numbers.

Problem 21: SSTF and C-SCAN Scheduling

Consider a disk with the disk head currently located on cylinder number 100 and moving outside (towards bigger numbered cylinder numbers). Assume that the current disk requests are for the following cylinders of the disk: 30, 12, 150, 120, 105, 160, 55, 77, 88. For the following disk scheduling algorithms, show in what order the requests will be served.

(a) Shortest Seek Time First

(b) C-SCAN

Problem 22: Disk Scheduling with Multiple Algorithms

Assume that the disk request queue consists of the following disk requests specified by a cylinder number: 45, 24, 123, 56, 124, 100, 80. Further assume that the disk arm is currently located over the cylinder number 88. In what order would the requests be scheduled by this file system if the file system employs:

(a) First Come First Served (FCFS) policy?

(b) Shortest Seek Time First (SSTF) policy?

(c) SCAN policy? Assume the disk head is moving towards increasing cylinder numbers.

(d) C-SCAN policy? Assume the disk head is moving towards increasing cylinder numbers.

Problem 23: SSD Lifespan Estimation

An SSD has the following characteristics:

(a) Write amplification factor (WAF): 2, i.e., each write causes a total of 2 writes on the SSD

(b) Endurance: 1000 write cycles per block

(c) Total capacity: 500 GB

(d) A workload writes 100 GB of data to the SSD every day.

Estimate the SSD’s lifespan in years, assuming all blocks are written evenly (wear leveling is perfect)

Instructor Solution

Total writes per day: 2x100 GB = 200 GB.

Total endurance: 500GBx1000cycles = 500000 GB

Lifespan: (Total endurance)/(Total writes per day) = 500x 103GB/200GB/day = 2500 days ~ 6.85 years

Elaboration (by LLM):

This problem ties together several SSD concepts: write amplification, endurance ratings, and wear leveling. Let me walk you through the reasoning step-by-step.

Step 1: Understanding Write Amplification

Write amplification factor (WAF) = 2 means:

- Logical write: 100 GB (what the OS thinks it’s writing)

- Physical write: 100 GB × 2 = 200 GB (what actually gets written to NAND flash)

Why? Because SSDs can’t overwrite directly. They must:

- Read entire block into buffer

- Modify data

- Write entire block to new location

- Mark old block for garbage collection

This causes more physical writes than logical writes.

Step 2: Calculate Total Physical Writes Per Day

Step 3: Calculate Total Endurance

The SSD can sustain a total number of writes before wearing out:

Why “cycles per block”? Each block in the SSD can be written to ~1000 times before the NAND flash cells degrade. With wear leveling (perfect distribution), all 500 GB worth of blocks get equal wear, so the total is capacity × endurance.

Step 4: Calculate Lifespan

Convert to Years:

Real-World Context:

This is the theoretical maximum lifespan assuming:

- ✅ Perfect wear leveling (all blocks wear evenly)

- ✅ 100 GB writes every single day (weekends, holidays, too)

- ✅ No blocks fail before endurance limit

- ❌ Reality: Typically 5-7 years for consumer SSDs with similar specs

Why the Real Lifespan is Often Better:

- Not all days have 100 GB writes - average user writes 10-50 GB/day

- NAND flash is conservative - rated 1000 cycles but often lasts longer

- SSD controller has error correction - can extend life beyond minimum

- Thermal factors - cooler operation extends lifespan

Key Insight:

SSD lifespan is fundamentally about total data written divided by per-block endurance. This is why:

- High write workloads (databases, servers) wear out SSDs faster

- Consumer use (mostly reading) extends lifespan

- WAF matters - higher WAF reduces lifespan proportionally

Practical Example Comparisons:

| Workload | Writes/Day | WAF | SSD Lifespan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light (web browsing) | 10 GB | 2 | ~68 years |

| Medium (office work) | 50 GB | 2 | ~14 years |

| Heavy (video editing) | 100 GB | 2 | 6.85 years |

| Extreme (data center) | 500 GB | 3 | 0.68 years |

Another Way to Think About It:

This shows lifespan is:

- ↑ Better with larger capacity (more blocks to distribute wear)

- ↑ Better with higher endurance rating

- ↓ Worse with higher write workload

- ↓ Worse with higher WAF

Problem 24: File System Superblock Contents

List 2 items that are stored in the superblock of a file system.

LLM Solution

Superblock Contents:

The superblock is a special block (usually at block 0 or 1) that stores critical metadata about the entire file system.

Two Key Items Stored:

-

File System Size Information:

- Total number of blocks in the file system

- Number of inodes

- Block size (512B, 1KB, 4KB, etc.)

- Inode size

-

Free Space Information:

- Pointer to free block list (or bitmap of free blocks)

- Pointer to free inode list

- Number of free blocks remaining

- Number of free inodes remaining

Other Important Superblock Contents:

- File System Type: ext4, NTFS, APFS, etc.

- Creation Date/Time: When FS was formatted

- Last Mount Time: When last mounted

- Mount Count: How many times mounted

- Block Group Descriptors: Pointers to block group metadata

- Magic Number: Identifier (0xEF53 for ext4)

- Journal Pointer: For journaling file systems

Problem 25: External Fragmentation in Contiguous Files

What is external fragmentation in a system with contiguous files?

LLM Solution

External Fragmentation in Contiguous File Allocation:

External fragmentation occurs when free space is scattered into many small, non-contiguous fragments, making it difficult to allocate space for new files even though total free space may be sufficient.

Visual Example:

Initial State (empty disk):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ [Free: 1000 KB] │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

After some files:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ File A │ Free:100│ File B │ Free:150│ File C │ Free:120 │

│ 200 KB │ 100 KB │ 300 KB │ 150 KB │ 200 KB │ 120 KB │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Total free: 100 + 150 + 120 = 370 KB (seems OK)

Try to allocate new 200 KB file:

- Fragment 1: Only 100 KB ❌ (too small)

- Fragment 2: Only 150 KB ❌ (too small)

- Fragment 3: Only 120 KB ❌ (too small)

Result: Allocation FAILS even though 370 KB is free!

Cannot allocate 200 KB contiguous space.

Why External Fragmentation Happens:

- Files are created and deleted randomly

- Each deletion leaves a hole (free space)

- If file sizes vary, holes become scattered

- Over time, many small holes accumulate

- Even if total free space is large, no contiguous region is large enough

Impact on Performance:

- Allocation: May require data relocation or rejection

- Access Time: Fragmented files require multiple seeks (for files spanning fragments)

- System Performance: Increased disk I/O, slower access

Comparison with Internal Fragmentation:

| Type | Location | Cause | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| External | Between files | Deletion patterns | File A deleted leaves hole between B and C |

| Internal | Within blocks | Block size | 4KB block holds 3.5KB file, wastes 0.5KB |

Solutions:

- Defragmentation: Rearrange files to consolidate free space

- Paging/Segmentation: Don’t require contiguous allocation

- Best-Fit Allocation: Choose smallest fragment that fits

- Compaction: Periodically reorganize disk

Problem 26: Internal Fragmentation in File Systems

What’s internal fragmentation as it applies to a file system?

LLM Solution

Internal Fragmentation in File Systems:

Internal fragmentation occurs when a file uses less space than the block it’s allocated, wasting the unused portion of the block.

Example:

Block Size: 4 KB (4096 bytes)

File 1: 3.5 KB

Allocated: 4 KB block

Wasted: 0.5 KB (512 bytes) ← Internal fragmentation

File 2: 1 KB

Allocated: 4 KB block

Wasted: 3 KB (3072 bytes) ← Internal fragmentation

File 3: 4.2 KB

Allocated: 8 KB (2 blocks)

Wasted: 3.8 KB ← Internal fragmentation

Total wasted: 0.5 + 3 + 3.8 = 7.3 KB

Total allocated: 12 KB (3 blocks)

Fragmentation ratio: 7.3/12 = 60.8%

Why It Happens:

- Fixed Block Size: File system allocates in fixed-size units (4 KB, etc.)

- File Size Mismatch: Files rarely align perfectly with block boundaries

- Rounding Up: Must allocate entire block even if file doesn’t fill it

Impact:

- Wasted Space: Dead storage capacity

- Not Performance Related: Unlike external fragmentation, doesn’t affect access speed (file still in one block)

- Capacity Related: Affects usable disk space

Internal vs External Fragmentation:

| Aspect | Internal | External |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Within allocated blocks | Between allocated blocks |

| Cause | Block size vs file size | Deletion/allocation patterns |

| Impact | Wasted space | Access time + wasted space |

| Solution | Smaller blocks | Defragmentation/paging |

| Severity | Usually <50% | Can be >50% |

Real-World Impact:

Hard Drive: 1 TB

Block Size: 4 KB

10 million files (average 10 KB)

With 4KB blocks:

Average waste per file: ~2 KB

Total internal fragmentation: ~20 GB (2% loss)

With 64 KB blocks:

Average waste per file: ~32 KB

Total internal fragmentation: ~320 GB (32% loss)

With 512 B blocks:

Average waste per file: ~256 B

Total internal fragmentation: ~2.5 GB (0.25% loss)

BUT: More blocks, more overhead, slower I/O

Block Size Trade-offs:

| Small Blocks | Large Blocks |

|---|---|

| Less internal fragmentation | More internal fragmentation |

| More overhead | Less overhead |

| More seeks | Fewer seeks |

| Slower for large files | Slower for small files |

Problem 27: Contiguous Allocation

What is contiguous allocation? What difficulty occurs with contiguous allocation?

LLM Solution

Contiguous Allocation Definition:

Contiguous allocation is a file storage method where all blocks of a file are stored in consecutive positions on the disk. Files occupy one contiguous region of disk space.

How It Works:

File A: 5 blocks

┌───┬───┬───┬───┬───┐

│ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │ 4 │ 5 │ blocks 100-104

└───┴───┴───┴───┴───┘

Contiguous region

File B: 3 blocks

┌───┬───┬───┐

│ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │ blocks 110-112

└───┴───┴───┘

Contiguous region

Advantages:

- Fast Access: Sequential file access requires minimal seeking

- Simple: Easy to implement, easy to understand

- Low Overhead: Minimal metadata (just start block + length)

Directory Entry Example:

File A: Start block = 100, Length = 5 blocks

File B: Start block = 110, Length = 3 blocks

Difficulties with Contiguous Allocation:

1. External Fragmentation:

Disk layout after some allocations/deletions:

┌──────┬────────────┬──────┬──────┬──────┬──────┐

│ File │ Free │ File │ Free │ File │ Free │

│ A │ (8 blocks) │ B │ 3 │ C │ 10 │

└──────┴────────────┴──────┴──────┴──────┴──────┘

Want to allocate new 6-block file:

- Free space 1: 8 blocks ✅ (fits)

- Free space 2: 3 blocks ❌ (too small)

- Free space 3: 10 blocks ✅ (fits)

Problem: Even with 21 blocks free, allocation difficult

if multiple files require exact sizes.

2. File Growth Problem:

Original:

File A: blocks 100-104 (5 blocks, currently using 4)

Now need to add 2 more blocks:

┌───────────────┬──┬────────┐

│ File A │XX│ File B │

│ 100-104 │105│ 106-110

└───────────────┴──┴────────┘

Cannot grow in-place! Must:

1. Allocate new space (blocks 120-126, 7 blocks)

2. Copy File A data to new location

3. Update directory entry

4. Release old blocks (external fragmentation)

Result: High overhead, slow

3. Allocation Difficulty:

During allocation, must find contiguous free space large enough:

Worst case: Scan entire disk looking for contiguous region

Expensive operation

Pre-allocation required: May allocate more than needed

Wastes space

4. Space Underutilization:

If file grows beyond pre-allocated space:

- Must move entire file to larger contiguous region

- Old space becomes fragmented

- Can’t use partial regions

Solutions (used in practice):

- Extent-Based Allocation: File composed of multiple contiguous extents

- Linked Allocation: Blocks linked via pointers (eliminates fragmentation)

- Indexed Allocation: Index blocks point to file blocks

- Paging: Virtual memory style (modern approach)

Modern File Systems:

Modern systems don’t use pure contiguous allocation because difficulties outweigh benefits. Instead:

- ext4/NTFS: Use extent-based (multiple contiguous regions)

- Benefits: Fewer seeks than fully scattered, easier growth than pure contiguous

Problem 28: Linked Allocation Fragmentation

Can linked allocation in a file system have external fragmentation? Internal fragmentation?

LLM Solution

Analysis of Fragmentation in Linked Allocation:

Linked Allocation Method:

Each block contains:

- Data (512 B - 4 KB)

- Pointer to next block (4-8 B)

Example:

File A: blocks [100→105→110]

↓ ↓ ↓

[Data...→105] [Data...→110] [Data...→-1(end)]

External Fragmentation: NO ❌

Linked allocation does NOT have external fragmentation because:

- Any free block can be used - blocks don’t need to be contiguous

- Scattered allocation is OK - pointers link them together

- No “large enough contiguous region” requirement - allocation always succeeds (until disk full)

Example:

Free blocks: scattered at positions 5, 47, 100, 200, 305, ...

Allocate new 5-block file:

Use any 5 free blocks: [5→47→100→200→305]

Disk layout:

┌────┬───┬─────┬───────┬───┬───┬─────┬────┐

│ FA │ * │ FB │ Free │ FA│ FC│ Free│ FA │

│ 1 │5 │ 2-3 │ 6-46 │100│47 │48-99│200 │

└────┴───┴─────┴───────┴───┴───┴─────┴────┘

*Pointer to next block

No external fragmentation!

Internal Fragmentation: YES ✅

Linked allocation DOES have internal fragmentation because:

- Fixed block size - still allocate in fixed-size blocks

- Last block may not fill completely - partial block waste

Example:

Block size: 4 KB (4096 bytes)

File size: 10.5 KB (10752 bytes)

Allocation:

Block 1: 4 KB (full)

Block 2: 4 KB (full)

Block 3: 2.5 KB (contains 2.5 KB data + 1.5 KB pointer)

But allocated 4 KB → waste 1.5 KB

Internal fragmentation: 1.5 KB per file (on average 2 KB wasted per file)

Summary:

| Type | Linked Allocation | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| External | NO | Any free block can be used; contiguity not required |

| Internal | YES | Fixed block size + last block may be partially full |

Impact:

- Better than contiguous: No external fragmentation (major advantage)

- Still has waste: Internal fragmentation similar to other methods

- Trade-off: Slower access (more seeks) for better allocation flexibility

Performance Comparison:

Contiguous: Fast access, external fragmentation problem

Linked: Slower access (more seeks), no external fragmentation

Indexed: Better access patterns, no external fragmentation

Problem 29: Advantages and Disadvantages of Linked Allocation

List 1 advantage and 1 disadvantage of using linked allocation in a file system?

LLM Solution

Linked Allocation Characteristics:

Advantage:

No External Fragmentation - The biggest advantage.

Files can be stored in any available blocks scattered across the disk. Unlike contiguous allocation, there’s no need for large contiguous regions. Allocation always succeeds as long as free blocks exist. This avoids the fragmentation problems that plague contiguous allocation and eliminates the need for periodic defragmentation.

Disadvantage:

Random Access is Slow - The biggest disadvantage.

To access block N of a file, must follow the chain of pointers:

- Block 0 → Block 1 → Block 2 → … → Block N

For large files, this becomes very slow. Reading block 1000 requires 1000 disk accesses (one per pointer follow). Sequential files are OK (decent caching), but random access patterns kill performance.

Example: Access byte at position 4,000,000 in a 5 MB file

Linked Allocation:

Block 0→Block 1→Block 2→...→Block 976 (1000 seeks!)

Time: ~1000 × 5ms = 5 seconds!

Indexed Allocation:

Look up index → go directly to Block 976 (1 seek)

Time: ~5ms

Problem 30: Single Directory Advantages and Disadvantages

List 1 advantage and 1 disadvantage of using a single directory.

LLM Solution

Single Directory File System:

All files stored in one flat directory (no subdirectories).

Advantage:

Simple Implementation - Easy to design and implement.

Only one directory to manage, linear search for files, minimal metadata overhead. No need for complex tree traversal algorithms or recursive directory operations. Users don’t need to remember complex path hierarchies.

Implementation:

Directory = { (filename, inode) }

Linear search: O(n) time

No need for:

- Path parsing

- Directory traversal

- Recursive operations

Disadvantage:

Naming Conflicts and Poor Organization - Multiple users can’t have files with same name.

With only one directory, all files share the same namespace. Two users can’t both create a file named “data.txt”. Files aren’t organized hierarchically, so thousands of files become unmanageable. Also, different file types (documents, images, programs) are all mixed together.

Single Directory:

data.txt ← User A's data

document.txt ← User B's data (CONFLICT!)

image.jpg ← Image file

program.exe ← Program file

temp.tmp ← Temporary file

(1000 more files) ← Chaos!

vs. Hierarchical:

/users/alice/documents/data.txt

/users/bob/documents/document.txt

/images/photo.jpg

/programs/app.exe

/temp/tempfile.tmp

(organized!)

Problem 31: DAG vs Tree Directory Issues

List two issues that must be addressed to handle Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) directories vs. simple tree directories.

Instructor Solution

(1) Backups need to be carefully written to not backup files with multiple names twice.

(2) Need to maintain reference counts in the i-nodes to know when the underlying file should be deleted.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Let me explain why these two issues are critical when you move from a simple tree directory structure to a DAG (Directed Acyclic Graph) structure.

Background: Tree vs DAG Directory Structure

In a simple tree directory:

- Each file has exactly ONE parent directory

- Each file has exactly ONE path

- Deletion is straightforward: delete the directory entry

Tree Structure:

/

├── alice/

│ └── thesis.pdf

└── bob/

└── project.txt

Each file has ONE parent, ONE path

In a DAG directory structure:

- Each file can have MULTIPLE parents (hard links)

- Each file can be accessed via MULTIPLE paths

- Deletion becomes complicated

DAG Structure:

/

├── alice/

│ └── thesis.pdf ──┐

├── bob/ ├─→ [inode 5000] → actual data

│ └── backup.pdf ──┘

│

Same file, TWO paths:

/alice/thesis.pdf

/bob/backup.pdf

Issue (1): Backup Problem

When you backup a filesystem with hard links (DAG), you must be careful not to backup the same file data twice.

Why this is a problem:

Scenario: Backup /alice/ and /bob/

Naive approach:

1. Backup /alice/thesis.pdf → Save inode 5000 data

2. Backup /bob/backup.pdf → Save inode 5000 data AGAIN!

Result: Backup has duplicate data, wasting backup space!

The solution:

Backup software must track inode numbers and ensure each inode is backed up only once:

Smart backup approach:

1. Encounter /alice/thesis.pdf (inode 5000)

→ Back up data once

→ Record: "inode 5000 backed up"

2. Encounter /bob/backup.pdf (inode 5000)

→ Already in backup set

→ Skip data, just record hard link

Result: Data saved once, backup efficient

Real-world impact:

Without this consideration, a filesystem with many hard links could double or triple backup size. Example:

Filesystem: 1 TB actual data

With many hard links, naive backup: 3 TB (3 copies!)

With smart backup: 1 TB (1 copy, hard link references)

Issue (2): Reference Counting for Deletion

In a DAG structure, you can’t simply delete a file when a user runs rm. You must track how many paths lead to that file.

Why reference counting is necessary:

Scenario: Multiple hard links to same file

/alice/thesis.pdf → [inode 5000] → [data]

/bob/backup.pdf ──→ [inode 5000] → [data]

/charlie/copy.pdf → [inode 5000] → [data]

Reference count: 3

When user deletes files:

Step 1: User deletes /alice/thesis.pdf

→ Remove directory entry

→ Decrement reference count: 3 → 2

→ Inode still exists (other paths depend on it!)

→ Data still on disk

Step 2: User deletes /bob/backup.pdf

→ Remove directory entry

→ Decrement reference count: 2 → 1

→ Inode still exists

→ Data still on disk

Step 3: User deletes /charlie/copy.pdf

→ Remove directory entry

→ Decrement reference count: 1 → 0

→ NOW reference count = 0!

→ Delete inode and data from disk

Without reference counting:

If we deleted data immediately on first `rm`:

User deletes /alice/thesis.pdf

→ File deleted from disk

But /bob/backup.pdf and /charlie/copy.pdf STILL POINT TO DELETED DATA!

→ "Dangling pointers"

→ Reading those paths: CORRUPTION or error

How reference count is stored:

In the inode itself, the OS maintains a link count:

struct inode {

int mode; // File permissions

int uid; // Owner user ID

long size; // File size

int link_count; // ← HOW MANY PATHS POINT HERE

char data_blocks[]; // Actual file data location

}When creating a hard link:

ln /alice/thesis.pdf /bob/backup.pdf

OS Action:

1. Create new directory entry in /bob/: "backup.pdf" → inode 5000

2. Increment link_count in inode 5000: 1 → 2

3. File now has 2 pathsWhen deleting:

rm /alice/thesis.pdf

OS Action:

1. Remove directory entry from /alice/: "thesis.pdf" deleted

2. Decrement link_count in inode 5000: 2 → 1

3. link_count > 0, so keep inode + data

4. /bob/backup.pdf still works!Verification in Unix/Linux:

$ echo "important" > file.txt

$ ls -l file.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 user group 10 Jan 4 12:00 file.txt

↑

link_count = 1

$ ln file.txt link1.txt

$ ln file.txt link2.txt

$ ls -l file.txt link1.txt link2.txt

-rw-r--r-- 3 user group 10 Jan 4 12:00 file.txt

-rw-r--r-- 3 user group 10 Jan 4 12:00 link1.txt

-rw-r--r-- 3 user group 10 Jan 4 12:00 link2.txt

↑

All show link_count = 3

$ rm file.txt

$ rm link1.txt

$ rm link2.txt ← Only NOW is data actually deletedSummary:

| Issue | Tree Directories | DAG Directories |

|---|---|---|

| Backup | Simple: Each file once | Must check inodes to avoid duplicates |

| Deletion | Delete immediately | Must use reference count to track when actual deletion happens |

| Complexity | Low | High - must manage reference counts |

| Benefit | Simple | Allows hard links, shared files, efficient storage |

These constraints are why modern filesystems with DAG support (ext4, NTFS, APFS) must implement reference counting and why backup tools need to be “inode-aware” to avoid data duplication.

Problem 32: Hard Link vs Soft Link

Explain the difference between a hard-link and a soft-link.

LLM Solution

Hard Links vs Soft (Symbolic) Links:

| Aspect | Hard Link | Soft Link |

|---|---|---|

| Points to | Same inode | Filename/path string |

| Type | Directory entry | Special file |

| Link count | Increments inode link count | Doesn’t affect original |

| Survives deletion | YES - inode still exists | NO - dangling link |

| Filesystem | Same filesystem only | Can cross filesystems |

| Circular refs | Can’t create cycle | Can create cycles |

| Overhead | Minimal | Extra inode + file |

Hard Link:

Original File:

/home/alice/data.txt → [inode 5000] → actual data

Hard Link:

/home/alice/backup.txt → [inode 5000] → same data

Link count: 2

Both point to SAME inode!

Deleting one file leaves the other intact

(data only deleted when link count = 0)

Creation:

ln original.txt hardlink.txt

Soft (Symbolic) Link:

Original File:

/home/alice/data.txt → [inode 5000] → actual data

Symbolic Link:

/home/alice/shortcut.txt → [inode 6001] → "/home/alice/data.txt" (path string)

Inode 6001 is a special "symlink" file containing path string

Dereferencing:

1. Read symlink content → get path "/home/alice/data.txt"

2. Look up path in filesystem

3. Access original inode 5000

If original deleted:

Symlink becomes "dangling" (broken)

Creation:

ln -s original.txt symlink.txt

Visual Comparison:

Hard Link Example:

User A's File: /home/alice/thesis.pdf → [Inode 5000] ← /home/alice/backup_thesis.pdf

↓

[PDF Data]

Both paths point to same inode

Delete thesis.pdf: backup_thesis.pdf still works

Soft Link Example:

User A's File: /home/alice/thesis.pdf → [Inode 5000] → [PDF Data]

User B's Link: /home/bob/view_thesis → [Inode 6001] → "/home/alice/thesis.pdf"

(symlink file)

Symlink contains path string, not direct inode reference

Delete thesis.pdf: symlink becomes broken link

Practical Differences:

Hard Links:

- Both names are equally valid

- Can’t tell which is “original”

- Useful for backups (transparent)

- Can’t span filesystems

- Can’t link to directories (filesystem integrity)

Soft Links:

- One is original, one is link

- Can see it’s a link (

ls -l) - Useful for shortcuts

- Can span filesystems

- Can link to directories

Problem 33: Hard Link After File Deletion

Assume that user A owns a file named “file.txt” and user B has a hard link to this file named “file1.txt”. Assume user A removes “file.txt” by issuing the Linux command “rm file.txt”. Now user B tries to access “file1.txt” by executing the command “file1.txt”. Will user B be able to access this file? Why or why not? Briefly explain.

LLM Solution

Answer: YES, user B can still access file1.txt

Explanation:

Hard links point to the same inode, not through filenames. When user A deletes “file.txt”:

- OS removes the directory entry “file.txt”

- Link count decreases from 2 to 1 (file1.txt still references it)

- Inode and data remain because link count > 0

- User B’s “file1.txt” still points to the same inode

- Data is still readable through file1.txt

Mechanism:

Before deletion:

Directory /home/alice/:

"file.txt" → [inode 5000]

Directory /home/bob/:

"file1.txt" → [inode 5000]

Inode 5000:

Link count: 2

Data: [actual file content]

User A: rm file.txt

After deletion:

Directory /home/alice/:

(file.txt entry removed)

Directory /home/bob/:

"file1.txt" → [inode 5000]

Inode 5000:

Link count: 1 ← Decreased by 1

Data: [actual file content] ← Still exists!

User B: access file1.txt

Result: SUCCESS - can read data through inode 5000

Key Point:

Hard links are at the inode level, not the filename level. The data is only deleted when:

- Link count becomes 0 (all directory entries removed)

Since file1.txt still references inode 5000, the data persists.

Contrast with Soft Link:

If file1.txt were a soft link:

Before deletion:

file.txt → [inode 5000] → [data]

file1.txt → [inode 6001] → "/home/alice/file.txt"

After deletion of file.txt:

file1.txt → [inode 6001] → "/home/alice/file.txt" (BROKEN PATH!)

Result: user B gets "file not found" error

Problem 34: Soft Link After File Deletion

Assume that user A owns a file named “file.txt” and user B has a soft link to this file named “file1.txt”. Assume user A removes “file.txt” by issuing the Linux command “rm file.txt”. Now user B tries to access “file1.txt” by executing the command “file1.txt”. Will user B be able to access this file? Why or why not? Briefly explain.

LLM Solution

Answer: NO, user B cannot access file1.txt - it becomes a dangling/broken link

Explanation:

Soft links contain the pathname of the original file, not the inode. When user A deletes “file.txt”, the pathname becomes invalid:

- Soft link file1.txt contains: “/home/alice/file.txt”

- User A removes file.txt → directory entry deleted

- Inode becomes unreachable

- When user B accesses file1.txt:

- OS reads symlink → gets path “/home/alice/file.txt”

- Tries to look up path → “file not found”

- Error: “file1.txt: No such file or directory”

Mechanism:

Before deletion:

/home/alice/file.txt → [inode 5000] → [data]

/home/bob/file1.txt → [inode 6001] → "/home/alice/file.txt" (symlink)

User A: rm file.txt

After deletion:

/home/alice/file.txt (REMOVED)

/home/bob/file1.txt → [inode 6001] → "/home/alice/file.txt" (BROKEN!)

Inode 5000: Unreachable (no directory entry points to it)

Link count: 0 (if no other links)

Data: Deleted

User B: access file1.txt

Step 1: Read symlink content → "/home/alice/file.txt"

Step 2: Try to look up path → Not found!

Step 3: Error! "file1.txt: No such file or directory"

Visual Diagram:

Soft Link (Pathname-based):

Before:

file1.txt ──→ [symlink inode 6001]

↓

"/home/alice/file.txt" ✅ Valid

↓

[inode 5000] ✅

↓

[data]

After rm file.txt:

file1.txt ──→ [symlink inode 6001]

↓

"/home/alice/file.txt" ❌ Invalid!

↓

[doesn't exist]

Result: Dangling link (broken)

Verification in Linux:

# Create original file

$ echo "content" > file.txt

# Create soft link

$ ln -s file.txt link.txt

# Access soft link - works

$ cat link.txt

content

# Delete original

$ rm file.txt

# Try to access soft link - fails!

$ cat link.txt

cat: link.txt: No such file or directory

# But symlink file itself still exists!

$ ls -l link.txt

lrwxrwxrwx 1 user user 8 Jan 4 12:34 link.txt -> file.txt

Notice the arrow still points to deleted fileKey Difference from Hard Links:

| Operation | Hard Link | Soft Link |

|---|---|---|

| Delete original | Still accessible | Broken link |

| Works because | Same inode | Contains path string |

| If inode exists | Data persists | Path invalid |

Problem 35: UNIX File System Protection Bits

What are the 9 protection bits used in a UNIX filesystem?

Instructor Solution

Read, write, and execute for each of user, group, and other/world

Elaboration (by LLM):

Let me break down these 9 protection bits and show you how they work in practice.

The 9 Protection Bits Structure

UNIX file permissions are organized as 3 groups of 3 bits each:

User Group Other

───── ───── ─────

r w x | r w x | r w x

7 5 1 | 7 5 1 | 7 5 1

r = read (4) w = write (2) x = execute (1)

Breaking it down:

-

User (Owner): 3 bits

- r (read): Can owner read the file? (4)

- w (write): Can owner modify the file? (2)

- x (execute): Can owner execute the file? (1)

-

Group: 3 bits

- r (read): Can group members read the file? (4)

- w (write): Can group members modify the file? (2)

- x (execute): Can group members execute the file? (1)

-

Other (World): 3 bits

- r (read): Can everyone else read the file? (4)

- w (write): Can everyone else modify the file? (2)

- x (execute): Can everyone else execute the file? (1)

Practical Examples

$ ls -l

-rw-r--r-- alice staff 1024 Jan 4 thesis.pdf

^ ^^^^^^^ ^^^^^ ^^^^^

| ||||||| ||||| |||||

| ||||||| ||||| └─ Other: r-- (read only)

| ||||||| └──────────── Group: r-- (read only)

| └────────────────────── User: rw- (read+write)

└─ File type: - (regular file)

Permissions: 644 (rw- r-- r--)How to read octal notation (644):

644 = 6 (user) + 4 (group) + 4 (other)

6 = 4 (read) + 2 (write) + 0 (no execute) = rw-

4 = 4 (read) + 0 (no write) + 0 (no execute) = r--

4 = 4 (read) + 0 (no write) + 0 (no execute) = r--

Result: rw- r-- r--

Common Permission Patterns

| Octal | Symbolic | File Type | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 644 | rw-r—r— | Regular file | Owner: read+write, Group: read, Other: read |

| 755 | rwxr-xr-x | Program | Owner: full access, Others: read+execute |

| 700 | rwx------ | Sensitive | Owner only (privacy) |

| 777 | rwxrwxrwx | Script | Everyone: full access |

| 600 | rw------- | Private | Owner reads+writes, nobody else |

Understanding Each Permission

1. Read (r = 4)

On regular file:

-rw-r--r-- file.txt

User can read? YES (r)

Group can read? YES (r)

Other can read? YES (r)