07 - Memory Management

Problem 1: Variable Partitioning in Memory Management

What’s variable partitioning in memory management? Briefly explain.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Variable Partitioning in memory management is when a process arrives you reserve a partition exactly as large as the process’s memory needs. Because the holes can be of any size, you can still suffer external fragmentation.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Variable partitioning is a memory allocation scheme where the OS dynamically allocates and deallocates memory partitions based on actual process requirements, rather than using fixed-size partitions.

How Variable Partitioning Works:

- Allocation: When a process arrives requesting

KB of memory, the OS finds a free hole and allocates exactly KB to it - Deallocation: When a process terminates, the OS reclaims its partition, creating a new hole

- Fragmentation Problem: Over time, free memory becomes scattered in many small holes

Visual Example:

Initial state:

P3 (5KB) arrives - doesn’t fit in any single hole:

Total free memory:

After deallocation of P2, we can fit P3:

But now we have fragmented free space:

Why External Fragmentation is Still a Problem:

Even though variable partitioning is efficient in terms of memory use per process, it leads to external fragmentation: the total free memory may be large enough to fit a process, but it’s fragmented across multiple holes, with no single hole large enough. This is the key disadvantage that motivated the development of paging systems.

Problem 2: Physical Addresses and Their Problems

In early architectures CPUs used to generate physical addresses to access RAM. What kind of problems did physical addresses create and how did memory management mechanisms solve these problems?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Using physical addresses caused a few problems, one of them being that if the process wasn’t loaded at the expected address, the memory references would be incorrect. To fix this, compilers generated relocation records. With this, the OS loader adjusted memory references using the relocation records to ensure correctness.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Early computer systems required programmers and compilers to work directly with physical memory addresses, which created significant challenges.

Problems with Physical Addresses:

- Hardcoded Addresses: A compiled program contained hardcoded references like “load value from physical address 0x1000”. This assumed the program would always be loaded at the same location

- Inflexibility: If two processes needed to run simultaneously, they would conflict at the same physical address

- Memory Fragmentation: The OS couldn’t move processes around to reduce fragmentation because all memory references were hardcoded

- Security Risk: One process could reference another’s physical memory directly

Example Problem:

Program compiled with absolute addresses:

Address 0x1000: load global_var

Address 0x1004: store to 0x2000

If OS loads program at 0x5000 instead:

The references still point to 0x1000 and 0x2000 ❌ WRONG!

Solution: Relocation Records and Base Addresses:

The compiler generated relocation records listing all memory references that needed adjustment:

Compiler output:

Instructions: [...]

Relocation records: [0x1000 is relocatable, 0x2000 is relocatable]

OS Loader:

Load address = 0x5000

For each relocation record:

old_address += load_address

Update instruction at that location

Result: 0x1000 becomes 0x6000, 0x2000 becomes 0x7000 ✅

This approach allowed programs to be loaded at any physical address, but was tedious and error-prone. Modern systems use virtual addressing instead, where the hardware (MMU) handles translation automatically at runtime.

Problem 3: Global Variable Address in Multiple Processes

Assume you have a simple program that declares a global variable and prints its address on the screen. When you run two copies of this program simultaneously, you see that both programs print the same address on the screen. How is this possible? Briefly explain.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

This is possible because what is printed is the virtual address, and the virtual address points to the same location in memory, that being the location of the global variable.

Elaboration (by LLM):

This is a fundamental insight into how virtual addressing works and why two independent processes can have the same virtual address for different data.

Why Both Processes Print the Same Address:

Program source code:

static int global_var = 42;

printf("Address: %p\n", &global_var);

Process A: Process B:

Compiler assigns: Compiler assigns:

global_var → virtual addr 0x1000 global_var → virtual addr 0x1000

Prints: "Address: 0x1000" Prints: "Address: 0x1000"

MMU Translation (invisible to process):

Process A: Virtual 0x1000 → Physical 0x5000

Process B: Virtual 0x1000 → Physical 0x8000

Key Insight: Virtual Address Space is Per-Process

Each process has its own virtual address space of identical layout. Since the compiler generates the same virtual address for global_var in both copies of the program, and the printf statement prints the virtual address (not the physical address), both processes print the same number.

However, the physical addresses are completely different:

- Process A’s global_var is actually stored at some physical location (say, 0x5000)

- Process B’s global_var is stored at a completely different physical location (say, 0x8000)

Practical Implication:

This design allows:

- Multiple independent processes to run the same program

- Each has its own memory isolated from the others

- Processes don’t need to know about physical memory locations

- The OS/MMU transparently maps virtual → physical addresses

If processes could see physical addresses, they would conflict when trying to use the same memory region!

Problem 4: External Fragmentation in Memory Management

What’s external fragmentation in memory management? Is external fragmentation a problem in paging systems? Briefly explain.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

External fragmentation occurs when you use variable partitioning to load processes into memory. It is when the free slots within the memory are not big enough to hold the incoming process consecutively. Even if the TOTAL free memory is big enough to fit a new process, there may be no single contiguous slot large enough!

Elaboration (by LLM):

External fragmentation is a critical problem in memory management systems using variable partitioning. It represents a gap between available memory and usable memory.

The Core Problem - Total ≠ Usable:

Total free memory:

New process arrives:

Can the 6KB process fit? ❌ NO! No single hole is

How External Fragmentation Develops:

- Process arrivals and departures: Processes come and go, leaving gaps

- Variable-sized holes: Each hole size depends on which process was there previously

- Poor allocation choices: Allocating processes suboptimally creates many tiny holes

- Compounding effect: As system runs longer, more holes accumulate

Visualization of Worsening Fragmentation:

Time 0:

Time 1:

Time 2:

Time 3:

System has 17 KB free total, but largest hole is only 7 KB!

Is External Fragmentation a Problem in Paging Systems?

No! Paging completely eliminates external fragmentation because:

- Memory is divided into fixed-size frames

- Processes are divided into fixed-size pages

- A page always fits into a frame, regardless of fragmentation

- Pages don’t need to be contiguous in physical memory

Trade-off Introduced by Paging:

While paging solves external fragmentation, it introduces internal fragmentation (wasted space within an allocated page if the process doesn’t use it fully). However, internal fragmentation is typically smaller than external fragmentation.

Problem 5: Internal Fragmentation

What’s internal fragmentation? In what memory management method does internal fragmentation occur? Briefly explain.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Internal fragmentation is when a process does not use all of the memory allocated to it. This is because when the OS allocated memory in fixed-size chunks, a process may not need the full chunk that has been provided.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Internal fragmentation is the “wasted” memory within an allocated block that a process doesn’t actually use. It’s the opposite of external fragmentation in both cause and location.

Key Difference from External Fragmentation:

| Aspect | Internal Fragmentation | External Fragmentation |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Inside allocated memory | Between allocated blocks |

| Cause | Fixed allocation size | Variable-size holes |

| Memory is fragmented? | Yes, but allocated anyway | No, it’s unused |

| Example | 4KB page with 1KB process (3KB wasted) | 7KB total free split as 2KB+3KB+2KB |

When Internal Fragmentation Occurs:

Internal fragmentation happens in memory management systems that allocate fixed-size blocks, specifically:

- Paging: Pages have fixed size (e.g., 4KB). If a process needs 5KB, it gets 2 pages (8KB), wasting 3KB

- Fixed Partitioning: Partitions have fixed size. If partitions are 16KB and a process needs 15KB, 1KB is wasted

- Slab Allocation: Object caches allocate fixed-size slabs; if not perfectly filled, space is wasted

Concrete Example - Paging with 4KB Pages:

Process A needs 6 KB of memory

Page size = 4 KB (fixed)

Allocation:

Usage:

Waste:

Internal fragmentation ratio

Comparison of Both Fragmentation Types:

External Fragmentation (Variable Partitioning):

Total free: 3 KB, but no usable hole

Internal Fragmentation (Paging):

Waste in Page 1: 1 KB | Waste in Page 2: 2 KB | Total waste: 3 KB (all allocated, some unused)

Why Paging Still Wins Overall:

Although paging introduces internal fragmentation, it’s generally preferable because:

- Internal fragmentation is bounded: max waste = page_size - 1 bytes per process

- External fragmentation is unbounded: can waste huge amounts as system fragments

- Internal fragmentation can be minimized with smaller page sizes (trade-off with page table overhead)

Problem 6: Variable Partitioning with Memory Allocation

Consider a system that uses variable partitioning for memory management. Assume that the system has 32KB total memory and the current snapshot of the memory is as follows:

Assume that the following 2 processes arrive in the given order: P4(4KB), P5(1KB). For each of the following memory management techniques, show the final state of the memory after the processes are allocated memory.

(1) First fit

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

First Fit (P4: 4KB, P5: 1KB):

Initial State:

First fit allocates P4 to the first hole that fits (5KB hole). Then P5 fits in any remaining hole.

Then P5 (1KB) fits in the 1KB hole:

Elaboration (by LLM):

First Fit is the simplest memory allocation algorithm. The OS maintains a list of free holes and allocates to the first hole that is large enough.

Algorithm:

for each hole in order:

if hole.size >= process.size:

allocate process to this hole

break

Advantages and Disadvantages:

Pros:

- Fast: Only scan until first fit is found, no need to check all holes

- Simple to implement: Just iterate through hole list

- Good for quick allocations

Cons:

- May waste memory: First hole might be much larger than needed, creating tiny remaining holes

- Can lead to fragmentation: After many allocations/deallocations, creates many unusable small holes

Analysis of the Example:

P4 (4KB) scans holes in order: 5KB ✅ (first fit found!), allocates here

- Remaining in 5KB hole: 5 - 4 = 1KB

P5 (1KB) scans holes from start: 1KB ✅ (first fit found!), allocates here

- This 1KB hole is completely used

Why First Fit Left the 10KB Hole Untouched:

First Fit doesn’t need to look at the larger 10KB hole because it already found a suitable hole (the 5KB hole). This is efficient for allocation speed but may not be optimal for memory utilization. Notice that the 10KB hole remains completely free—this is common with First Fit.

(2) Best Fit

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Best Fit (P4: 4KB, P5: 1KB):

Initial State:

Best fit allocates P4 to the smallest hole that fits (4KB hole):

Then P5 (1KB) fits in the 5KB hole:

Elaboration (by LLM):

Best Fit is a memory allocation strategy that tries to minimize wasted space by allocating to the smallest hole that still fits the process.

Algorithm:

best_hole = null

for each hole:

if hole.size >= process.size:

if (best_hole == null) or (hole.size < best_hole.size):

best_hole = hole

allocate process to best_hole

Advantages and Disadvantages:

Pros:

- Minimizes waste: Allocates to smallest suitable hole, leaving larger holes for future processes

- Better fragmentation: Tends to reduce external fragmentation compared to First Fit

- Improves allocation success: Larger holes available for larger incoming processes

Cons:

- Slower: Must scan all holes to find the best one (O(n) vs O(1) for First Fit)

- Still creates small holes: The remaining space in the “best” hole becomes a new tiny hole

- Overhead: The cost of scanning all holes may outweigh benefits

Detailed Analysis of the Example:

Available holes: [5KB, 10KB, 4KB]

P4 (4KB) needs best fit:

- 5KB hole: fits, size = 5 (candidate)

- 10KB hole: fits, size = 10 (not better than 5)

- 4KB hole: fits, size = 4 (BEST! smaller than 5)

Allocate P4 to 4KB hole → no waste!

P5 (1KB) needs best fit among remaining: [5KB, 10KB, 4KB]

- 5KB hole: fits, size = 5 (candidate)

- 10KB hole: fits, size = 10 (not better than 5)

- 4KB hole: already used

Allocate P5 to 5KB hole → leaves 4KB hole

Comparison to First Fit Result:

First Fit left: 10KB hole unused (waste) Best Fit left: 10KB hole unused, but better fragmentation overall

Best Fit is theoretically superior but has higher CPU overhead.

(3) Worst fit

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Worst Fit (P4: 4KB, P5: 1KB):

Initial State:

Worst fit allocates P4 to the largest hole (10KB hole):

Then P5 (1KB) fits in the 6KB hole:

Elaboration (by LLM):

Worst Fit is a counterintuitive strategy that allocates to the largest available hole, with the idea that this leaves large holes for future allocations.

Algorithm:

worst_hole = null

for each hole:

if hole.size >= process.size:

if (worst_hole == null) or (hole.size > worst_hole.size):

worst_hole = hole

allocate process to worst_hole

Motivation Behind Worst Fit:

The intuition is: “Allocate to the largest hole so the remaining hole is still reasonably large for future processes.”

Advantages and Disadvantages:

Pros:

- Preserves large holes: After allocation, remaining space is still sizeable

- Allows larger future processes: Future large processes have more options

- Theory: Should reduce external fragmentation

Cons:

- Wastes large holes: Uses large holes even when smaller ones suffice

- Actually performs worse: Empirical studies show Worst Fit performs poorly in practice

- Fragments available space: Creates many medium-sized holes instead of keeping one large hole

- Slower than First Fit: Still O(n) to find maximum

Detailed Analysis of the Example:

Available holes: [5KB, 10KB, 4KB]

P4 (4KB) needs worst fit:

- 5KB hole: fits, size = 5 (candidate)

- 10KB hole: fits, size = 10 (WORST! largest)

- 4KB hole: fits, size = 4 (not worst)

Allocate P4 to 10KB hole → leaves 6KB hole

P5 (1KB) needs worst fit among remaining: [5KB, 6KB, 4KB]

- 5KB hole: fits, size = 5

- 6KB hole: fits, size = 6 (WORST! largest)

- 4KB hole: fits, size = 4

Allocate P5 to 6KB hole → leaves 5KB hole

Why Worst Fit Usually Fails:

Suppose many 2KB processes arrive next:

After P4, P5: [5KB hole] [6KB hole] [4KB hole]

After 2 more 2KB: [1KB] [2KB] [2KB] [2KB]

Now lots of 2KB holes, no 5KB+ hole available!

Comparison:

- Best Fit: Preserves large 10KB hole longer

- Worst Fit: Breaks up the 10KB hole unnecessarily

Empirical Results:

In practice, Best Fit performs best, then First Fit, and Worst Fit performs worst despite its theoretical motivation.

Problem 7: Memory Allocation Algorithms

Given free memory partitions of 100K, 500K, 200K, 300K and 600K (in order) how would each of the Firstfit, Best-fit, and Worst-fit algorithms place processes of 212K, 417K, 112K and 426K (in order)? Which algorithm makes the most efficient use of memory?

LLM Solution

First Fit: Places 212K in 500K, leaving 288K. Places 417K in 600K, leaving 183K. Cannot place 112K (all remaining partitions too small). Cannot place 426K.

Best Fit: Places 212K in 300K, leaving 88K. Places 417K in 600K, leaving 183K. Places 112K in 500K, leaving 388K. Cannot place 426K.

Worst Fit: Places 212K in 600K, leaving 388K. Places 417K in 500K, leaving 83K. Cannot place 112K. Cannot place 426K.

Best-fit makes the most efficient use of memory in this case since it successfully allocates 3 processes compared to the others.

Elaboration:

This problem demonstrates the practical differences between allocation algorithms with realistic workloads.

Initial State:

Available partitions (in order):

Memory Layout (Initial):

First Fit Trace:

Best Fit Trace:

Actually, reviewing: After Step 2, remaining holes are

Let me re-trace:

Key Insight - Algorithm Comparison:

| Algorithm | P1 (212K) | P2 (417K) | P3 (112K) | P4 (426K) | Processes Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Fit | ✅ (500K) | ✅ (600K) | ❌ | ❌ | 2 |

| Best Fit | ✅ (300K) | ✅ (600K) | ✅ (200K) | ❌ | 3 |

| Worst Fit | ✅ (600K) | ✅ (500K) | ❌ | ❌ | 2 |

Why Best Fit Wins:

Best Fit’s strategy of choosing the smallest suitable partition preserves larger partitions:

- Best Fit placed 212K in 300K (not 500K), preserving the 500K for later processes

- First Fit greedily took 500K for 212K, leaving insufficient holes for P3

- This allowed Best Fit to successfully allocate three processes vs. two for the others

Outcome Metric: Best Fit achieved 3/4 allocations (75%) vs. First Fit and Worst Fit with 2/4 (50%)

General Takeaway:

Best Fit is empirically superior because:

- Minimizes waste in each allocation

- Preserves larger holes for larger future processes

- Results in fewer allocation failures

However, Best Fit requires scanning all partitions (slower), making it a CPU-efficiency vs. memory-efficiency trade-off.

Problem 8: Variable Partitioning with Base and Limit Registers

Briefly explain how memory management with variable partitioning and a simple MMU with base and limit registers works. Does this memory management scheme use physical or logical addresses?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

This memory management scheme uses physical addresses! How it works is that a logical address (offset) is fed into a memory management unit (MMU), and the MMU checks if the logical address is valid for the process. The MMU contains 2 registers, base and limit. The base is the base address for the current process, and the limit contains the size of the partition. If the value in the base + offset is out of bounds of the process’s limit, then a page fault is made. If it is within bounds, then the MMU directs to the process’s base address which is in the base register, and adds the offset to grab the requested memory.

Elaboration (by LLM):

This is a transition point between early physical addressing and modern virtual addressing. The scheme uses base and limit registers—a simple but powerful MMU design that enables protection and relocation without full virtual memory.

How Base-Limit MMU Works:

The MMU translates logical addresses to physical addresses using a simple addition formula:

Concrete Example:

Where:

- CPU generates: logical address =

(offset within process) - MMU base register =

(where process is loaded in physical RAM) - MMU limit register =

(process size = 16KB)

Boundary Check:

Before accessing, MMU verifies:

If check fails: Protection violation (trap to OS)

Result: CPU accesses physical RAM location

Key Features:

- Relocation: Process can be loaded at any physical address by just changing the Base register

- Protection: Limit register prevents process from accessing beyond its partition

- Simplicity: Only 2 hardware registers needed

Address Translation Flow:

CPU

|

logical address ($0x2000$)

|

v

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ MMU (Hardware) │

│ │

│ $\text{Base} = 0x5000$ │

│ $\text{Limit} = 0x4000$ │

│ │

│ Check: $\text{addr} < \text{limit}$? │

│ Compute: $\text{addr} + \text{base}$ │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

|

physical address ($0x7000$)

|

v

RAM

Advantages vs Disadvantages:

Pros:

- Simple hardware: Only 2 registers

- Fast translation: Single addition operation

- Protection: Prevents accessing other processes

- Relocation: Solves the physical address problem

Cons:

- Requires contiguous memory: Process must fit in one contiguous block

- External fragmentation: Still suffers from variable partitioning

- No paging: Cannot use pages for more flexible memory management

Comparison to Modern Virtual Addressing:

Base-Limit is essentially “simple virtual addressing”:

- Virtual address ≠ Physical address ✅

- Automatic translation at runtime ✅

- Protection between processes ✅

- But no paging, so external fragmentation remains ❌

Modern systems use page tables instead of base-limit because page tables:

- Allow non-contiguous allocation

- Eliminate external fragmentation

- Enable demand paging (pages in/out to disk)

Problem 9: Virtual vs Physical Addresses

What’s a virtual address? How does it differ from a physical address? Briefly explain.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

A virtual address is the address used by a program to access memory. It’s generated by the CPU during program execution. It does not refer to the physical location in memory, instead it is translated into physical memory by the MMU, which is an actual location in memory

Elaboration (by LLM):

Virtual and physical addresses are fundamental concepts in modern memory management. Understanding their relationship is crucial to understanding how operating systems isolate and protect processes.

Key Definitions:

| Concept | Virtual Address | Physical Address |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Address used by program/CPU | Actual location in RAM hardware |

| Who generates | CPU core (during instruction execution) | MMU during translation |

| Is same across processes? | NO - each process has own space | YES - all processes share RAM |

| Translation | Virtual → Physical via MMU/page tables | Hardware bus to RAM |

| Visibility to program | YES - used by code | NO - transparent to program |

Virtual Address Space (per Process):

Each process has identical virtual address spaces, but they map to different physical locations:

Process A Virtual Space:

- Code segment:

(physical) - Data segment:

(physical) - Stack segment:

(varies)

Process B Virtual Space:

- Code segment:

(physical) ← different physical address! - Data segment:

(physical) ← different physical address! - Stack segment:

(varies)

Key Insight: Same virtual address (

Process A Virtual: 0x08000000 ──MMU──→ Physical: 0x3000

Process B Virtual: 0x08000000 ──MMU──→ Physical: 0xAB00

Why Separate Virtual and Physical Addresses?

- Relocation: Programs always see memory starting at 0x0, regardless of where OS loads them

- Protection: Process A can’t access Process B’s pages (MMU enforces this)

- Multitasking: Multiple processes can run; each thinks it has whole memory

- Paging: Pages can be scattered in RAM or swapped to disk; program doesn’t care

- Abstraction: Hardware details (RAM layout, fragmentation) hidden from programs

Example with C Code:

int x = 42; // Variable stored at virtual address (e.g., 0x1234)

int *p = &x; // p stores virtual address 0x1234

printf("%p", p); // Prints virtual address (e.g., 0x1234)What happens when this code runs:

- Expression

&xevaluates to:(what program sees) - When CPU accesses

*p, MMU translates:(physical) - CPU reads from physical RAM location:

, retrieves value - Translation is automatic; C program never directly sees

Security Without Virtual Addressing:

❌ Without virtual addressing (old systems):

Program A writes to

Program B writes to

✅ With virtual addressing (modern systems):

Program A writes to

Program B writes to

Result: Same virtual address maps to different physical locations ✅ Protected!

This explains why modern multi-process operating systems REQUIRE virtual addressing—it’s the only way to safely run multiple programs simultaneously.

Problem 10: Process Swapping

Briefly explain what process swapping is and what it was used for? In modern paging systems, is process swapping employed? Why or why not?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Process swapping occurs when a high priority process needs to be loaded into memory to be executed but there is not enough space. In this case an entire lower priority process is removed from memory and put into a backing store, and the new process is put into memory to be executed. In modern paging systems, process swapping is NOT employed. This is because paging moves smaller memory units (pages) and not the entire process.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Process swapping is a memory management technique from the era of variable partitioning. It represents a drastic measure to make room for high-priority processes.

When Swapping Occurs:

Memory state:

[P1: 8KB] [P2: 12KB] [P3: 6KB] [Free: 2KB]

High-priority P4 (10KB) arrives and needs to run immediately.

Problem: No contiguous 10KB hole available.

Solution (Swapping):

1. Find lowest-priority process (e.g., P2)

2. Save P2's entire memory (12KB) to disk (backing store/swap disk)

3. Free P2's 12KB partition

4. Load P4 (10KB) into memory

5. Later, restore P2 from disk when more space available

Memory after swap:

[P1: 8KB] [P4: 10KB] [P3: 6KB] [Free: 2KB]

Disk: [P2: 12KB saved]

Characteristics of Swapping:

Granularity: Entire process (all its memory) Frequency: Infrequent (only when necessary) Trigger: High-priority process arrival + insufficient contiguous space Overhead: Very high (I/O cost to disk)

Cost Analysis:

Swapping a 12KB process:

Disk access time:

Seek time: ~5-10 ms

Transfer 12KB: ~0.2 ms

Total: ~10 ms for one process

Context switch time: ~1-2 ms

Swap cost >> context switch cost by 5-10x!

Why Swapping is Expensive:

Disk I/O is the bottleneck in computer systems:

CPU speed: 1-3 GHz (1-3 ns per instruction)

Disk speed: 10-15 ms latency + transfer time

Ratio: 10 million × slower!

Swapping an entire process is catastrophic for performance.

Why Modern Systems Use Paging Instead:

Swapping (Variable Partitioning):

[P1: 8KB] [Hole: 5KB] [P2: 12KB] [Hole: 3KB]

New process (10KB): Must swap entire P2 → disk I/O cost!

Paging (Fixed Pages, e.g., 4KB):

[P1 page 1] [Hole: 4KB] [P2 page 1] [Hole: 4KB] [P2 page 2] [Hole: 4KB]

New process: Can allocate 3 pages (12KB) in non-contiguous holes

→ No need to swap anything!

Paging’s Advantages Over Swapping:

| Feature | Swapping | Paging |

|---|---|---|

| Granularity | Entire process | Individual pages (4KB) |

| Frequency | Infrequent | Very frequent (transparent) |

| Allocation | Requires contiguous space | Works with fragmented space |

| I/O cost | High per operation | Amortized low (many processes) |

| Use case | Rare (priority inversion) | Continuous (demand paging) |

Modern Paging Analogy:

Instead of swapping entire books to storage, paging swaps individual pages:

Have 10 books but shelf space for 8:

- Swapping: Remove entire book B1, store on shelf, later swap it back

Cost: Move whole book multiple times

- Paging: Keep most-used pages of all books on shelf,

swap least-used pages to storage, rotate as needed

Cost: Move small units frequently, but overall efficient

When Swapping Still Happens:

Modern OSs use swapping but at page granularity:

Linux: Memory pressure → pages swapped to swap space on disk

(not entire processes)

Windows: Similar page-based swapping in virtual memory manager

True “process swapping” (entire process) is obsolete in modern systems.

Problem 11: Segmentation for Memory Management

Briefly explain the motivation behind segmentation for memory management and how it works?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

The motivation behind segmentation in memory management was to avoid external fragmentation. Before segmentation, the entire process need to be loaded into main memory in a contiguous memory space, which made it so that large processes could not be loaded when there was not enough contiguous space. Segmentation works to fix this by breaking up a process into parts: Code, Data, Stack. These parts are able to be place any where in the memory space and do not have to be contiguous with each other!

Elaboration (by LLM):

Segmentation was an intermediate memory management approach that addressed one of the key limitations of variable partitioning: external fragmentation.

The Core Problem Segmentation Solves:

Before segmentation, the entire process had to be allocated as a single contiguous block. When you have 3 KB, 2 KB, and 1 KB of holes scattered throughout memory but need 5 KB contiguous space, external fragmentation makes that allocation impossible.

Segmentation divides each process into logical segments (Code, Data, Stack, etc.). Each segment is fixed or grows at its own rate, and they can be placed in different memory locations, not necessarily adjacent to each other.

Key Advantages:

- Non-Contiguous Allocation: Segments can be placed in different memory locations, allowing use of scattered free space

- Logical Protection: Each segment can have different access rights (code=execute only, data=read/write)

- Shared Segments: Code segments of shared libraries can be mapped to multiple processes

- Reduces External Fragmentation: Though not eliminating it entirely

Why It Wasn’t the Final Solution:

While segmentation reduced fragmentation, processes still needed contiguous allocation for each segment. This meant:

- Small gaps still remained between segments

- Segment sizes are variable, making memory management complex

- Programmers must create segments explicitly

Comparison to Paging (What Replaced Segmentation):

Paging takes the concept further by dividing BOTH physical and virtual memory into fixed-size units (pages/frames), completely eliminating external fragmentation. Modern systems use paging because it’s simpler and more effective.

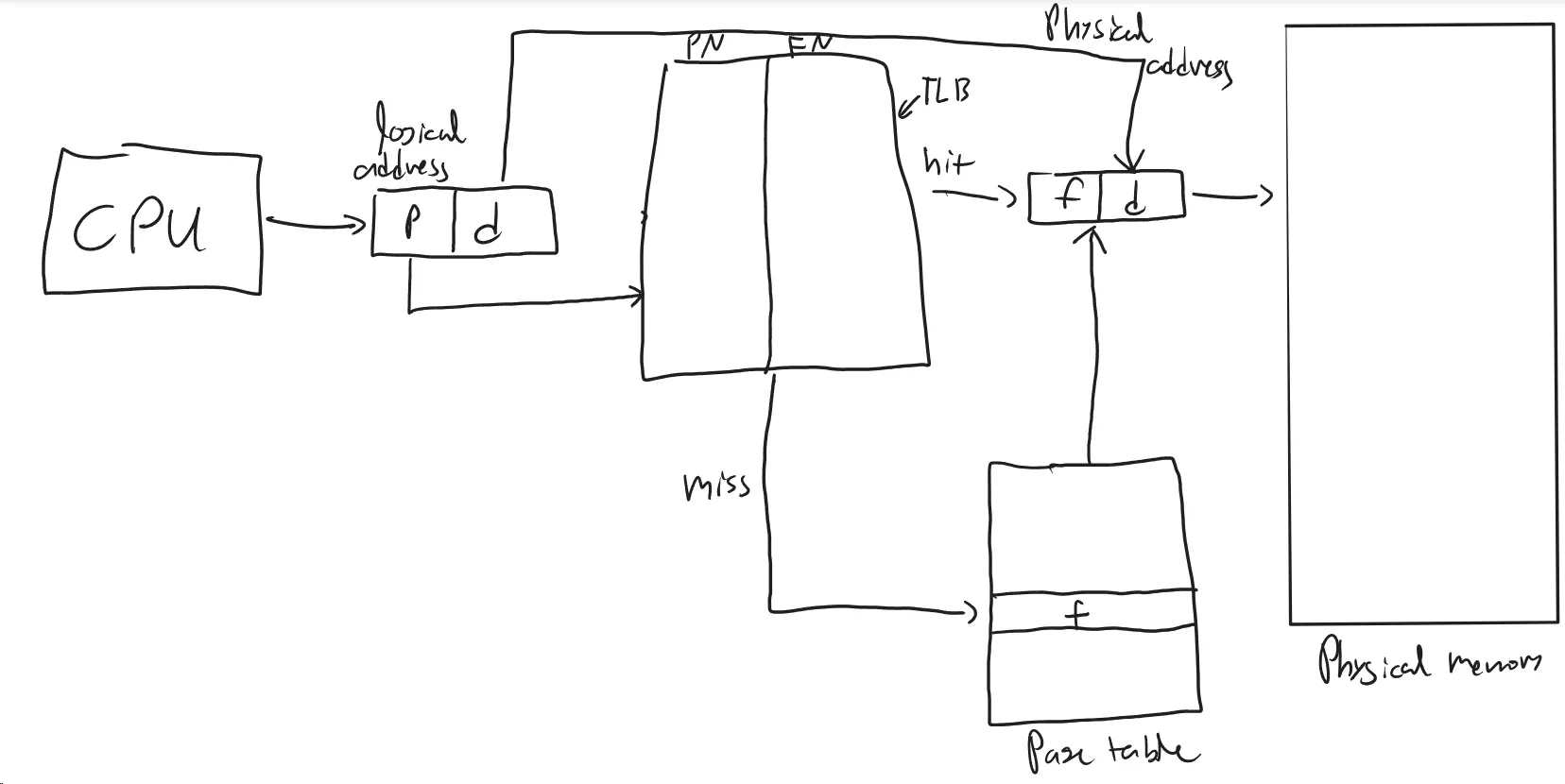

Problem 12: Paging and Hardware Support

All modern memory management schemes use paging. Briefly explain the main motivation behind paging and if paging requires hardware support.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

The main motivation behind paging was to create a solution for external fragmentation. External fragmentation made it so that large processes could not be loaded into memory to be executed if there was not enough contiguous space for it to be held. This problem was solved with paging, by breaking the memory into equal sized slots called frames, and breaking the processes up into pages of the same size, so that they may always fit into non-contiguous frames. Paging does require hardware support, as it requires a MMU.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Paging is the fundamental memory management technique in all modern operating systems. It completely solves the external fragmentation problem by using fixed-size allocation units.

Why External Fragmentation is Eliminated:

The key insight is that all pages and frames are the same size. If a 4 KB page needs to be placed, it can fit into ANY 4 KB frame—there’s no size mismatch. This guarantees complete memory utilization with no wasted gaps.

Without paging (variable-size blocks):

- Holes: 5 KB, 2 KB, 3 KB (scattered)

- Process needs 4 KB → Fits in 5 KB hole, but 1 KB wasted

- Process needs 6 KB → Can’t fit, even though 10 KB total free

With paging (fixed 4 KB blocks):

- Frames available: As many as needed

- Page needs 4 KB → Fits perfectly in exactly one frame

- Multiple pages → Each fits perfectly, no wasted space

Why Hardware Support (MMU) is Essential:

Paging REQUIRES hardware support for three critical reasons:

-

Translation Speed: Every memory access needs virtual→physical translation. Software translation would be too slow (microseconds vs nanoseconds needed).

-

Protection: Hardware must enforce that processes don’t access each other’s pages—this must happen at CPU cycle speed, not software speed.

-

Concurrency: With multiple processes rapidly context switching, hardware must handle translation with zero overhead.

The MMU (Memory Management Unit) contains:

- Page Table Lookup: Translates virtual address to physical address

- TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer): Cache of recent translations

- Permission Checking: Validates access rights on every access

What Makes Paging Superior:

Compared to segmentation, paging:

- Completely eliminates external fragmentation (vs. reducing it)

- Transparent to programmers (no explicit segment creation)

- Enables virtual memory (page swapping to disk)

- Simpler hardware implementation

Problem 13: Page Table Entry Contents

List 3 things that are stored in a Page Table Entry (PTE) and briefly explain what each is used for?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

-

Modify bit: The modify bit signals if the page has been modified (if the page is dirty)

-

Reference bit: The reference bit signals if the page has been read or written to

-

Frame Number: Which frame this page belongs to

Elaboration (by LLM):

A Page Table Entry (PTE) is the metadata structure that controls how the MMU and OS manage that page. Understanding PTE contents is critical to understanding paging systems.

The Three Key Fields in This Answer:

Each PTE contains multiple fields. The three mentioned are among the most important:

1. Frame Number (Mandatory)

This field stores the physical frame address where this page resides. When a page is loaded into memory, the OS updates this field with the frame number. This is how the MMU translates virtual page numbers to physical frame numbers.

Example: If virtual page 5 is in physical frame 203, PTE[5] contains 203.

2. Dirty Bit (Modified Bit)

This 1-bit flag indicates whether the page has been written to since it was loaded from disk.

- Dirty = 0: Page hasn’t been modified → when evicted, just free the frame (fast)

- Dirty = 1: Page modified → must write back to disk before freeing frame (slow, ~10-100ms)

The OS uses this for page replacement optimization: prefer evicting clean pages to avoid expensive disk writes.

3. Reference Bit (Accessed Bit)

This 1-bit flag indicates whether the page has been accessed (read OR written) recently. The MMU sets this to 1 whenever the page is accessed. The OS periodically clears it to 0.

Usage: Page replacement algorithms like LRU (Least Recently Used) examine this bit. Pages with reference = 0 are candidates for eviction because they haven’t been used recently.

Other Important PTE Fields Not Mentioned:

While the solution lists three, complete PTEs typically include:

- Valid Bit: Is this page in memory (1) or on disk/swap (0)?

- Protection Bits: What operations are allowed (read, write, execute)?

- Cache Disable: Should this page be cached (important for I/O memory)?

Example: How These Fields Are Used

When a process tries to access memory address 0x5234 (page 5, offset 0x234):

- MMU looks up PTE[5]

- Checks Valid bit = 1 (page is in memory)

- If valid = 0 → Page Fault (page is on disk, must load)

- If valid = 1 → Extract Frame Number (e.g., 203)

- Set Reference bit = 1 (mark as accessed)

- Form physical address: (203 << 12) | 0x234

- Access memory location

If code later writes to this page: 8. CPU sets Dirty bit = 1 (mark as modified)

When page replacement needed: 9. OS examines Dirty bit → if 1, must write to disk first 10. OS examines Reference bit → if 0, this is a good candidate to evict

Problem 14: Advantages and Disadvantages of Paging

List 1 advantage and 1 disadvantage of paging.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

One advantage of paging is that it eliminates external fragmentation One disadvantage is that it is memory reference intensive. By that I mean when accessing memory you had to make 2 references rather than one (page table, then memory)

Elaboration (by LLM):

This answer correctly identifies the fundamental trade-off in paging: it solves fragmentation at the cost of additional memory references.

Advantage: Eliminating External Fragmentation

This is paging’s primary benefit. External fragmentation was the chronic problem with variable partitioning and segmentation—wasted space accumulating over time, preventing allocation of new processes.

With paging’s fixed-size units, this is completely eliminated:

- 4 KB page always fits in any 4 KB frame

- No holes, no wasted gaps between allocations

- System remains usable indefinitely without defragmentation

Disadvantage: Memory Reference Overhead (Mitigated by TLB)

The student correctly identifies that accessing memory now requires two references:

- First reference: Look up page table to get frame number (~100 ns)

- Second reference: Access actual memory at that frame (~100 ns)

This doubles access time compared to direct memory systems!

However, the Solution: TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer)

Modern systems solve this with a TLB—a hardware cache of recent virtual→physical translations:

- TLB hit (90% of time): Single lookup + memory access = ~110 ns (only 10% slower)

- TLB miss (10% of time): Two lookups + memory access = ~200 ns (double speed)

Weighted average: 0.9 × 110 + 0.1 × 200 = 119 ns (~19% slowdown)

So while the trade-off is real, TLB hardware makes it negligible in practice.

Other Disadvantages of Paging:

-

Page Table Memory Overhead:

- 32-bit system: ~4 MB per process just for page tables

- Solution: Multi-level page tables save 95%+ of this

-

Internal Fragmentation:

- Last page of process may not be fully used

- Bounded: maximum waste = (page_size - 1) bytes

- Negligible (~0.2% of memory)

-

TLB Flush on Context Switch:

- When switching processes, TLB becomes invalid

- Solution: Process ID tagging in TLB

The Big Picture:

| Aspect | Before Paging | With Paging | With Paging+TLB |

|---|---|---|---|

| External Fragmentation | 30-50% | 0% | 0% |

| Memory Overhead | Minimal | 4 MB per process | 4 MB per process |

| Access Time | 100 ns | 200 ns (2x) | 119 ns (1.2x) |

This comparison shows why paging dominates: the trade-offs are manageable, while the benefits are transformative.

Problem 15: Multi-level Page Tables

What’s the motivation behind multi-level page tables? Briefly explain.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

The motivation behind multi-level page tables is to save memory used by page tables in systems with large virtual address spaces. This is because single-level page tables must have one page table entry (PTE) for every page, even if the pages are not in use. To combat this, page tables are broken up into multiple levels, and only the parts of the page table needed for currently used addresses are kept in memory. This decreases memory use, but increases memory reference overhead.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Multi-level page tables are a crucial innovation that made paging practical for modern systems with large address spaces.

The Problem: Single-Level Page Table Overhead

For a 32-bit system with 4 KB pages:

Each PTE = 4 bytes, so each process needs:

The Waste: Even with 100 processes, that’s 400 MB just for page tables—and most processes don’t use their entire virtual address space!

Typical process:

- Virtual address space allocated: 4 GB (all 32 bits)

- Actually used: ~100 MB (code, data, stack, heap)

- Wasted page table: ~4 MB (entries for unused 3.9 GB)

Solution: Multi-Level Page Tables

Instead of one flat table, create a hierarchy. Only allocate lower-level tables as needed.

Two-Level Example:

Single-level: One 1M-entry table (4 MB)

Two-level: One 1K-entry directory (4 KB)

+ 50 1K-entry tables (200 KB for used regions)

Total: ~204 KB (saved 3.8 MB!)

How Two-Level Page Tables Work:

- Page Directory: 1024 entries (4 KB)

- Each entry points to a page table (or NULL if unused)

- Page Tables: Multiple tables, allocated on-demand

- Each table is 1024 entries (4 KB)

- Only allocated for used regions of virtual space

Memory Savings:

| Address Space | Single-Level | Two-Level | Savings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-4 MB (code/data) | 1 MB | 8 KB | 99.2% |

| Used heap | (included in above) | 4 KB | 99.6% |

| Stack region | (included in above) | 4 KB | 99.6% |

| Unused (3.9 GB) | 3.9 GB | 0 KB | 100% |

| Total per process | 4 MB | ~20 KB | 99.5% |

Trade-off: Memory References

Multi-level tables require more lookups:

- Single-level: 1 page table access + 1 memory access = 2 accesses

- Two-level: 1 directory + 1 table + 1 memory = 3 accesses

- Three-level: 1 directory + 2 table lookups + 1 memory = 4 accesses

However, TLB masks this overhead:

- TLB caches the final translation (virtual page → physical frame)

- With TLB hit (~95%), all intermediate lookups are skipped

- Net result: ~1.2× slowdown instead of 2-4×

Three-Level Page Tables (64-bit Systems)

Modern 64-bit systems use 3-4 level hierarchies:

Linux x86-64:

PML4 (1024 entries)

├─ PDP (1024 entries)

├─ Page Directory (1024 entries)

└─ Page Table (1024 entries)

This handles 48-bit virtual address spaces efficiently:

- One 4 KB directory per process

- Only allocates deeper tables as needed

- Scales elegantly to massive address spaces

Real-World Impact:

Multi-level page tables enabled:

- Virtual memory systems (swapping pages to disk)

- Large address spaces (64-bit computing)

- Sparse allocation (only allocate what’s used)

- Process isolation (complete virtual address separation)

Without this optimization, page table overhead would consume significant physical memory, defeating the purpose of virtual memory.

Problem 16: 48-bit Virtual Addresses with 32-bit Physical Addresses

A machine has 48-bit virtual addresses and 32-bit physical addresses with a page size of 8KB.

(1) How many entries are needed for the page table?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

1 KB = 1024 =

48-bit address space →

Entries for page table → Address space size / size of pages =

Elaboration (by LLM):

This calculation reveals how virtual address space size determines page table complexity—a critical consideration for architecture design.

Understanding the Calculation:

The number of page table entries (PTEs) must equal the number of pages in the virtual address space.

Step 1: Convert Page Size to Bits

Given: Page size = 8 KB

Step 2: Calculate Number of Pages

Virtual address space:

This is a massive number:

Step 3: Page Table Entries

Each page needs exactly one PTE in the page table:

Why This Matters:

With

This is completely impractical! One process’s page table alone would consume more memory than typical servers have.

The Solution: Multi-Level Page Tables

This is precisely why multi-level page tables are essential for 48-bit address spaces:

- Single-level (flattened): 256 TB per process (impossible)

- Two-level: ~4 GB per process (still too large)

- Three-level (Intel x86-64): ~2 MB per process (practical!)

- Four-level (Linux): ~4 MB per process (with sparse allocation)

Virtual vs. Physical Address Spaces:

Important distinction this problem illustrates:

| Metric | Virtual | Physical |

|---|---|---|

| Address bits | 48 | 32 |

| Page size | 8 KB | 8 KB |

| Pages/Frames | ||

| PTE entries | 0 (not used for physical) | |

| Frame table | 0 (not used) |

The page table maps virtual pages to physical frames. So the table has one entry per virtual page, but only physical frames are limited by physical memory size.

Practical Example:

For this 48-bit virtual / 32-bit physical system:

- Process can address: 256 TB of virtual memory

- System has: 4 GB of physical memory

- Page table entries needed: 34 billion

- Pages actually in memory at any time: ≤ 1 million

The page table is sparse—most entries are for pages currently on disk or never allocated.

(2) How many frames are there in the physical memory?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

- Frames need to be same size as pages → frame size = 8 KB =

- 32-bit address space =

- Number of frames = Address space size / size of frames =

Elaboration (by LLM):

This calculation demonstrates the relationship between physical memory capacity and the number of frames—a key constraint on system capacity.

Physical Memory Constraints:

Unlike virtual address space (which can be arbitrary), the number of frames is determined by actual physical RAM installed.

For this system:

- Physical memory:

- Frame size (must equal page size): 8 KB =

Number of Frames:

What This Means:

This system has exactly 524,288 physical frames available. This is the absolute upper bound on how many pages can be resident (in physical memory) at any moment.

Comparison: Virtual vs. Physical Limitations

| Aspect | Virtual (from Part 1) | Physical (from Part 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Address bits | 48 | 32 |

| Address space size | ||

| Pages/Frames | ||

| Page table size | 256 TB (why multi-level tables exist) | 4 MB frame table |

| Pages in memory | Limited to | 524,288 frames available |

Physical Address Format:

With

Example physical address:

- Frame 0x5A2 (19 bits)

- Offset 0x345 (13 bits)

- Physical address: 0x5A2345

Key Insight: Virtual vs. Physical Page Table Entries

This problem distinguishes two concepts:

- Part (1): Virtual page table has

- Part (2): Physical system has

A mismatch:

Solution: Virtual memory + paging to disk

- All

- Only

- OS swaps pages to disk as needed

- Page faults trigger disk I/O to load pages into free frames

Frame Table (OS Data Structure):

The OS maintains a frame table with

Frame Table (524,288 entries, ~2-4 MB)

Entry 0: [Process A, Page 5, Dirty=1, Pinned=0]

Entry 1: [Process B, Page 23, Dirty=0, Pinned=0]

Entry 2: [Kernel, Page 0, Dirty=0, Pinned=1]

...

Entry 524287: [Free]

Each entry tracks:

- Which process owns the frame

- Which virtual page it contains

- Dirty flag (write-back needed?)

- Pinned flag (cannot evict?)

Why Frame Count Matters:

System capacity fundamentally limited by physical frames:

- 524,288 frames with 8 KB pages = 4 GB memory (expected!)

- Each process competes for frames

- When all frames full + page fault occurs → page replacement needed

- Limited frames is why TLB and cache efficiency matter

Real-World Comparison:

| System | Physical Memory | Frame Size | Frames | Virtual Space |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32-bit (4 KB pages) | 4 GB | 4 KB | 1M | 4 GB |

| 64-bit server | 256 GB | 4 KB | 64M | 256 TB |

| This problem | 4 GB | 8 KB | 524K | 256 TB |

Modern servers have millions of frames; small embedded systems might have thousands.

Problem 17: Shared Page Frames

What is the effect of allowing two entries in a page table to point to the same page frame in memory? Explain how this effect can be used to decrease the amount of time and memory needed to copy a large amount of memory from one place to another. What would the effect of updating some byte in one page be on the other page? How would you make sure that updating a byte in one page does not change the same byte in the other page?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

If two entries in a page table point to the same page frame in memory, both pages refer to the same physical memory. That means any read from either page returns the same data, and any write to one page affects the other page. This decreases the amount of time and memory needed to copy a large amount of memory from one place to another because instead of actually moving the memory you can just have a new page point to the same physical address.

Problem 18: Logical Address Space with 8 Pages

Consider a logical address space of 8 pages of 1024 bytes each, mapped onto a physical memory of 32 frames.

(a) How many bits are there in the logical address?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

8 pages each 1 KB →

(b) How many bits are there in the physical address?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Frames space = 32 frames each frame 1 KB →

(c) If the OS requires all pages of process to be in memory for it to run, how many processes can the OS load to memory at the same time?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Problem 19: 32-bit Computer with Single-level Paging

Consider a 32-bit computer that has 1GB of physical memory. This machine employs single-level paging with 8192 byte (8 KB) frames.

(a) Show the parts of a virtual address, i.e., how many bits are used for offset, how many bits for indexing the page table?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

- Since page size =

- For indexing, virtual address is 32 bits, offset is 13, so

(b) How many physical frames does the machine have? How many virtual pages does the machine have? How many bytes does a process page table occupy in memory?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

- Physical frames → 1 GB =

- Virtual → 32-bit computer =

- Page table occupy size → # pages

(c) A user process generates the virtual address 0x345672F3. Compute the page number and offset from the virtual address and explain how the system establishes the corresponding physical location.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Virtual Address → 0x345672F3

- Page Number:

0x34567 - Offset:

0x2F3

To get the corresponding physical location, the system goes to the page that corresponds to the page number which will provide the frame number. Then the system will concatenate the offset to the frame number to get the physical location. For example if 0x34567 contained 0x12345 then the physical address is 0x123452F3.

(d) Assume that memory access takes 100 microseconds (100,000 nanoseconds). This machine uses TLB and TLB access takes 100 nano seconds. Assume a 90% TLB hit ration, compute the effective memory access time.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Where:

Problem 20: 16-bit Architecture with Single-level Paging

Consider a 16-bit architecture that uses single-level paging. Assume the frame size is 256 bytes, and the total physical memory size is 16KB.

(a) What’s the total virtual memory size? How many frames does the physical memory have?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

256 bytes →

Virtual memory size →

Frame # →

Elaboration (by LLM):

This problem illustrates the fundamental components of a paging system on a small 16-bit architecture.

Virtual Memory Size:

With a 16-bit architecture, each process can address:

This is the upper bound of addressable memory per process. All virtual addresses are 16 bits.

Physical Memory Constraint:

Total physical RAM installed: 16 KB =

This is quite small—modern systems have GB or TB, but this problem models a small embedded or historical system.

Frame Calculation:

Page size = 256 bytes =

Number of physical frames:

The system has exactly 64 frame slots to hold pages from any process.

System Capacity:

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Virtual address space | 64 KB per process |

| Physical memory | 16 KB total |

| Page size | 256 bytes |

| Frame size | 256 bytes |

| Total pages possible | 64 KB / 256 B = 256 pages |

| Total frames | 16 KB / 256 B = 64 frames |

Key Insight: Only 64 out of 256 possible pages can be in memory simultaneously. The rest must reside on disk.

Memory Layout Example:

Process A (address space: 0x0000 to 0xFFFF):

- Pages 0-9: Loaded in frames 5, 23, 12, 8, 3, 45, 18, 1, 52, 61

- Pages 10-255: On disk or unallocated

When Process A needs page 100 (currently on disk) and all 64 frames are full:

- OS uses page replacement algorithm (LRU, etc.)

- Evicts an existing page from memory

- Reads page 100 from disk into the freed frame

Process Page Table Structure:

Each process has its own page table with 256 entries:

Each entry is a PTE (typically 2-4 bytes for a 16-bit system).

Multi-process Example:

With 64 total frames and multiple processes:

- Process A: 20 pages in memory

- Process B: 30 pages in memory

- Process C: 10 pages in memory

- Process D: 4 pages in memory

- Total: 64 frames (fully utilized)

If Process E arrives wanting 10 pages, page replacement must happen (evicting pages from A-D).

(b) Draw the virtual address and show how many bits are used for offset and how many bits are used for page number.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Since page size is

Virtual address format:

Elaboration (by LLM):

This problem demonstrates address decomposition—how a virtual address is split into page number and offset, a critical concept for understanding address translation.

Why Offset Bits Equal Log₂(Page Size):

The offset must be able to address every byte within a page.

Given: Page size = 256 bytes =

Need

Why Remaining Bits Are Page Number:

Total address bits: 16 (for 16-bit architecture)

Bits used for offset: 8

Bits left for page number:

Address Format:

The solution shows offset first (bit positions 0-7, lowest order bits) and page number second (bit positions 8-15, highest order bits).

Or written left-to-right as the solution shows:

Example Address Decomposition:

Virtual address: 0xA5C2 (binary: 1010 0101 1100 0010)

- Offset (lower 8 bits): 0xC2 = 194 bytes

- Page number (upper 8 bits): 0xA5 = 165

This means: “In page 165, at byte offset 194 within that page”

How MMU Uses This Decomposition:

- Extract page number from upper 8 bits: 0xA5 = 165

- Look up page table entry: PT[165]

- Get frame number (e.g., 23)

- Extract offset from lower 8 bits: 0xC2 = 194

- Form physical address: (23 << 8) | 194 = 0x17C2

- Access RAM at location 0x17C2

Comparison Across Different Page Sizes:

| Page Size | Offset Bits | Page # Bits (16-bit) |

|---|---|---|

| 256 B ( | 8 | 8 |

| 128 B ( | 7 | 9 |

| 512 B ( | 9 | 7 |

For Larger Architectures:

32-bit system with 4 KB pages:

- Page size: 4 KB =

- Offset bits: 12

- Page number bits: 32 - 12 = 20

- Total pages:

64-bit system with 4 KB pages:

- Page size: 4 KB =

- Offset bits: 12

- Page number bits: 64 - 12 = 52

- Total pages:

Key Principle:

This address decomposition is hardware-encoded:

- The MMU physically separates the address bits

- Lower N bits automatically go to offset hardware

- Upper bits automatically go to page table lookup

The split is determined by page size and cannot be changed without hardware redesign.

(c) How many entries does a process’s page table have? What’s the size of a process’s page table?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

A process’s page table is

Elaboration (by LLM):

This solution clarifies the relationship between virtual address space size and page table dimensionality. (Note: The wording is slightly confusing—what’s really meant is “the process’s virtual address space is

Page Table Entries Calculation:

The number of page table entries equals the number of possible pages in the virtual address space.

Given:

- Virtual address space:

- Page size: 256 bytes =

Number of pages:

Therefore, the page table must have 256 entries.

Page Table Size in Memory:

Assuming each PTE is 2 bytes (for this 16-bit system):

Key Insight:

Each process must have a page table capable of mapping all 256 possible pages in its virtual address space. This is true regardless of how many pages are actually in memory.

Page Table Layout:

Process A's Page Table (256 entries, 512 bytes)

Entry 0: Frame 5 (page 0 is in frame 5)

Entry 1: Frame 23 (page 1 is in frame 23)

Entry 2: Invalid (page 2 not in memory)

Entry 3: Frame 8 (page 3 is in frame 8)

...

Entry 255: Invalid (page 255 not in memory)

Total size: 512 bytes in physical RAM

Resident vs. Non-Resident Pages:

The page table has 256 entries, but processes use far fewer frames:

| Aspect | Value |

|---|---|

| Possible pages | 256 (all entries in page table) |

| Pages in memory | Limited by 64 total frames |

| Example process | 20 pages in memory, 236 on disk |

When page 150 is accessed but not in memory:

- Page fault occurs

- OS finds page 150 on disk

- Page fault handler evicts a page using page replacement algorithm

- Loads page 150 into freed frame

- Updates PTE[150] with new frame number

Memory Usage Across Multiple Processes:

With N concurrent processes:

Examples:

- 5 processes: 2.5 KB for all page tables

- 10 processes: 5 KB for all page tables

- 32 processes: 16 KB for all page tables

This is quite small relative to the 16 KB physical memory!

Page Table Entry Details:

For this 16-bit system with 64 frames, each PTE likely contains:

| Field | Bits | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Frame number | 6 | (since |

| Valid bit | 1 | Is page in memory? |

| Dirty bit | 1 | Has page been modified? |

| Reference bit | 1 | Has page been accessed? |

| Protection bits | 2 | Read/write/execute |

| Other | 5 | Unused/reserved |

| Total | 16 bits = 2 bytes |

Comparison Across Architectures:

| System | Virtual Space | Page Size | Entries | Bytes/Entry | PT Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This problem | 64 KB | 256 B | 256 | 2 | 512 B |

| 32-bit system | 4 GB | 4 KB | 1M | 4 | 4 MB |

| 64-bit system | 256 TB | 4 KB | 64G | 8 | 512 GB |

Notice how page table size grows dramatically with address space! This is why multi-level page tables are essential.

Where Page Tables Live:

Page tables reside in physical memory:

- This 512-byte table occupies 2 of the 64 frames

- Multiple processes share the 64 frames: page tables + process data

- In page replacement, page tables themselves can be paged to disk (though OS typically pins them in memory)

Trade-off: Table Size vs. Flexibility

- Larger page tables consume more memory

- But smaller pages means more table entries (trade-off)

- This system chose 256-byte pages (compromise between overhead and internal fragmentation)

(d) Show a diagram that shows how address translation occurs. Draw TLB, page table and physical memory. Assume all pages of a process are in the memory for the process to run.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

(e) Assume TLB search takes 1ns and memory access takes 100ns. For a TLB hit rate of 90%, compute the effective memory access time.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Where:

Elaboration (by LLM):

Effective Memory Access Time (EMA) calculation is fundamental to understanding paging system performance. This problem shows how TLB hit rate dramatically affects overall memory performance.

Understanding the Two Scenarios:

Memory accesses fall into two categories based on TLB status:

Scenario 1: TLB Hit (probability = a = 0.90)

When the virtual→physical translation is cached in the TLB:

- TLB lookup: 1 ns (fast cache hit)

- Memory access: 100 ns

- Total: (1 + 100) = 101 ns

Scenario 2: TLB Miss (probability = 1 - a = 0.10)

When the translation is NOT in TLB (must consult page table):

- TLB lookup: 1 ns (search and fail)

- Page table access: 100 ns (first memory reference to get frame number)

- Memory access: 100 ns (second memory reference for actual data)

- Total: (1 + 100 + 100) = 201 ns

Formula Breakdown:

Where:

Calculation:

Performance Analysis:

System performance with 90% TLB hit rate:

- Ideal (direct memory, no paging): 100 ns

- With paging: 111 ns

- Overhead: 11%

Despite doubling memory accesses on TLB misses, the system is only 11% slower because TLB hits dominate (90% of accesses).

Impact of Changing TLB Hit Rate:

Varying the hit rate shows its dramatic effect on EMA:

| Hit Ratio (a) | Hit Cost | Miss Cost | EMA | Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% | 101 ns | 201 ns | 151 ns | 51% |

| 75% | 101 ns | 201 ns | 131 ns | 31% |

| 80% | 101 ns | 201 ns | 121 ns | 21% |

| 85% | 101 ns | 201 ns | 116 ns | 16% |

| 90% | 101 ns | 201 ns | 111 ns | 11% |

| 95% | 101 ns | 201 ns | 106 ns | 6% |

| 99% | 101 ns | 201 ns | 102 ns | 2% |

| 100% | 101 ns | - | 101 ns | 0% |

Sensitivity Analysis:

How much does each percentage point of hit rate matter?

Each 1% increase in TLB hit rate saves 1 ns of EMA:

- Improving from 80%→90%: saves 10 ns

- Improving from 90%→99%: saves 9 ns

This shows why TLB design is critical—small hit rate improvements yield significant system performance gains.

Why Real Systems Achieve High TLB Hit Rates:

Despite the threat of TLB misses, real systems consistently achieve 95%+ hit rates:

| Workload | Typical Hit Rate | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Sequential code | 99%+ | Instructions march through memory sequentially |

| Standard applications | 95-98% | Locality of reference (programs reuse memory) |

| Memory-intensive | 85-95% | Still good due to working set principle |

| Pathological (worst) | <50% | Random access patterns (rare in practice) |

Working Set Principle:

At any moment, a program actively uses only ~10-50 virtual pages. With a modern TLB having 100-1024 entries, the working set fits entirely in TLB, achieving near-perfect hit rates.

Real-World Comparison:

| System | TLB Entries | Typical WS | Hit Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Historical (Intel 386) | 4-8 | 20 pages | ~50% |

| Pentium IV | 64-128 | 30 pages | ~95% |

| Modern server | 512-1024 | 50 pages | ~99% |

Implication for System Design:

This analysis justifies why systems invest heavily in TLB:

- Large TLBs (1000+ entries): Small hardware cost for huge performance gain

- TLB prefetching: Predict future translations and load proactively

- Shared TLBs: Multiple cores share single large TLB

An additional 512 TLB entries might cost ~1% silicon but improve performance by 5-10%—an excellent trade-off.

Historical Context:

Early paging systems (1970s-1980s) with small TLBs (4-8 entries) saw 30-40% slowdowns. Modern systems with large TLBs achieve near-native performance, making paging practical for general-purpose computing.

Problem 21: Avoiding TLB Flush on Context Switch

We discussed in class that typically OSs keep a separate page table for each process. Since the logical address space of all processes are the same, the TLB must be flushed during a context switch. Suggest a fix that would NOT require the TLB to be flushed during a context switch. What are the implications of your suggestion?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

A fix that makes it so that the TLB does not have to be flushed during a context switch is using Context Identifiers! This makes it so that you can take TLB entries with which process they belong to. With this, translations from other processes can remain in the TLB but are ignored!

Elaboration (by LLM):

This solution identifies a critical performance problem in paging systems and its elegant hardware solution.

The Problem: TLB Invalidation on Context Switch

Without special handling, when the OS switches from Process A to Process B:

- Both processes have separate page tables (different virtual→physical mappings)

- Process A’s TLB entries are now invalid for Process B

- Example: Process A’s page 100 might be in frame 5, but Process B’s page 100 might be in frame 200

- If TLB still contains Process A’s translation and Process B accesses page 100, it gets wrong frame!

Why Flush Is Expensive:

- Clearing 100-1000 TLB entries: ~1000 CPU cycles

- Repopulating TLB: ~100 cycles per TLB miss

- Context switches happen 10,000+ times per second on busy systems

- Total overhead: 1-5% of CPU time wasted on TLB management

The Solution: Process ID (Context ID) Tagging

Instead of flushing, tag each TLB entry with the process ID:

TLB Entry Format (without ASID):

[Virtual Page] → [Physical Frame]

TLB Entry Format (with ASID/Context ID):

[ASID: 12 bits] [Virtual Page] → [Physical Frame]

How It Works:

- Storage: Each TLB entry also stores the process’s Address Space Identifier (ASID)

- On context switch: CPU register contains current ASID

- TLB lookup: Compare both virtual page AND ASID

- Match found → Translation valid, use it

- ASID mismatch → Entry ignored (belongs to different process)

Example:

Process A (ASID=1):

- Page 100 → Frame 5 (stored as [ASID=1, Page=100] → Frame 5)

Process B (ASID=2):

- Page 100 → Frame 200 (stored as [ASID=2, Page=100] → Frame 200)

Context Switch: CPU.ASID_register = 2

Process B accesses page 100:

- MMU checks TLB with [ASID=2, Page=100]

- Finds match [ASID=2, Page=100] → Frame 200

- Uses Frame 200 (correct!)

- Ignores [ASID=1, Page=100] entry (different ASID)

Performance Improvement:

| Approach | TLB Flush Cost | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Without Context ID | 1000 cycles per switch | None |

| With Context ID | 0 cycles (no flush needed) | 1-5% system performance gain |

Implications of This Solution:

-

Hardware Cost:

- Slightly larger TLB entries (12-16 bits for ASID)

- Comparator must match both ASID and page number

- Negligible cost (~1% more silicon)

-

Software Cost:

- OS assigns unique ASID to each process

- ASID pool limited (e.g., 4096 on ARM, 256 on older systems)

- ASID reuse after process exits

-

Effectiveness:

- Excellent for multi-process systems: Eliminates expensive TLB flushes

- Reduces latency: Context switches faster

- Improves throughput: CPU spends more time on useful work

-

Trade-offs:

- Requires OS to manage ASID allocation

- ASID exhaustion requires careful process lifecycle management

- Not beneficial for single-process systems

Real-World Adoption:

- ARM: ASID feature (ASID tagging)

- MIPS: ASID support in TLB

- x86: No native ASID; uses process ID in CR3 register (different approach)

- Modern systems: Virtually universal in multi-core CPUs

Why This Matters:

Context ID tagging is a perfect example of hardware-software co-design:

- Simple hardware change (tag each entry)

- Massive software benefit (eliminate expensive flushes)

- Enables efficient process-switching in modern OSs

Problem 22: TLB Hit Ratio and Effective Memory Access Time

The percentage of time that any page number is found in the TLB is called the hit ratio. Assume a TLB hit ratio of 90% and a single-level page table. If it takes 10 nanoseconds to lookup the TLB, and 100 nanoseconds to access memory, calculate the effective memory-access time.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Where:

Elaboration (by LLM):

This problem extends the earlier EMAT calculation by using different TLB parameters and explicitly showing the three-reference cost of a TLB miss with single-level page tables.

Key Difference from Problem 20(e):

Problem 20 had:

- TLB access: 1 ns (faster cache)

- Memory access: 100 ns

- Formula:

Problem 22 has:

- TLB access: 10 ns (slower cache)

- Memory access: 100 ns

- Formula:

Why Three References on Miss?

With single-level page tables:

TLB HIT Path (1 reference):

1. TLB lookup: 10 ns (hit!) → get frame number

2. Memory access: 100 ns → get data

Total: 110 ns

TLB MISS Path (3 references):

1. TLB lookup: 10 ns (search, fail)

2. Page table access: 100 ns → read PTE to get frame number

3. Memory access: 100 ns → read actual data

4. Cache in TLB: (hardware automatic)

Total: 210 ns

The extra 10 ns for TLB lookup vs. the earlier 1 ns reflects different hardware implementations (larger, slower TLB vs. fast L1 cache).

Formula Breakdown:

Note: The first

Calculation Details:

Performance Analysis:

Compare to direct memory (no paging):

- Direct: 100 ns (baseline)

- With paging: 130 ns

- Overhead: 30%

This is higher than Problem 20(e)‘s 11% overhead due to:

- Slower TLB: 10 ns vs. 1 ns (10× slower)

- Single-level page tables: 3 refs vs. 2 refs on miss

TLB Efficiency Analysis:

With slower TLB (10 ns), the hit rate becomes more critical:

| Hit Ratio | EMAT | Overhead |

|---|---|---|

| 75% | 60% | |

| 80% | 50% | |

| 85% | 40% | |

| 90% | 30% | |

| 95% | 20% | |

| 99% | 12% |

Key Insight:

With a slower TLB (10 ns), reaching 99% hit rate is essential to keep overhead reasonable. This explains why modern systems invest heavily in:

- Large TLBs (1000+ entries)

- TLB prefetching

- Fast TLB access (priority over page table performance)

Comparison: Multi-level vs. Single-level Page Tables

With 2-level page tables on miss, we’d add another memory reference:

The extra level adds 10 ns to miss case (41 vs. 31), demonstrating the trade-off between page table memory efficiency and access time.

Real-World Implication:

This problem highlights why designers must balance:

- TLB size: Larger TLBs → higher hit rates but slower access

- Page table levels: More levels → save memory but slower on miss

- System performance: Must achieve 90%+ TLB hit rates to remain practical

Problem 23: 32-bit Virtual Addresses with 2-level Page Table

Suppose your machine has 32 bit virtual addresses and uses a 2-level page table. Virtual addresses are split into a 9 bit top-level page table field, an 11 bit second level page table field, and an offset. How large are the pages? How many pages are there in the virtual address space? If the machine has 1GB physical memory, how many frames does the memory have?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Page size:

- 32 bits total = 9 bits + 11 bits + offset → offset = 12 bits

- Page size =

Number of pages:

- Top-level bits + second-level bits = 9 + 11 = 20 bits

- Number of pages =

Number of frames:

- Physical memory = 1 GB =

- Frame size =

- Number of frames =

Elaboration (by LLM):

This problem demonstrates how address bits are distributed in 2-level page table systems—a key concept for understanding modern virtual memory architectures.

Address Decomposition Logic:

The 32-bit virtual address must be split into three components:

Why Offset = 12 Bits:

The offset is determined by page size, not architectural design:

- Given: Page size = 4 KB =

- Need to address

- Therefore: offset bits = 12

This is fixed. The remaining bits (32 - 12 = 20) are split between the two page table levels.

Why 9 + 11 Split:

The designers chose an asymmetric split (9 + 11) rather than symmetric (10 + 10):

Design Options:

- Symmetric: 10 + 10 (cleaner, more common)

- Asymmetric: 9 + 11 (this problem's choice)

Both are valid; split depends on system characteristics.

2-Level Page Table Structure:

Directory and Table Sizes:

Top-level (Page Directory):

- Entries:

- Size:

- Always resident in memory

Second-level (Page Tables):

- Per table entries:

- Per table size:

- Multiple tables (up to 512, one per directory entry)

- Total possible:

- Actually allocated: only for used regions

Total Virtual Pages:

Each process needs 1 million page table entries spread across the 2-level hierarchy.

Memory Savings Comparison:

| Approach | Size per Process |

|---|---|

| Single-level | |

| 2-level | 4 KB (directory) + used tables (typical: 20 KB) = 24 KB |

| Savings | 99.7% memory saved! |

Address Translation Example:

Virtual address: 0x12345678

Binary: 0001 0010 0011 0100 0101 0110 0111 1000

Split:

- Top-level index (bits 31-23): 000 0100 10 = 0x12 (entry 18 in directory)

- Second-level index (bits 22-12): 011 0100 0101 = 0x345 (entry 837 in table)

- Offset (bits 11-0): 0110 0111 1000 = 0x678 (offset 1656 in page)

Translation Hardware (2-level):

Virtual Address: 0x12345678

↓

1. Extract top-level index: 0x12 (9 bits)

Access Page Directory[0x12] → Frame F1

↓

2. Extract second-level index: 0x345 (11 bits)

Access Page Table (in frame F1) at entry 0x345 → Frame F2

↓

3. Extract offset: 0x678 (12 bits)

Physical address = (F2 << 12) | 0x678

↓

4. Access physical memory at computed address

Physical Memory Calculations:

Physical memory: 1 GB =

With 4 KB pages, number of frames:

Frame numbers are 18 bits (different from page numbers!):

Virtual vs. Physical Address Spaces:

| Aspect | Virtual | Physical |

|---|---|---|

| Address bits | 32 | ~18 (varies by memory size) |

| Page numbers | 20 bits ( | - |

| Frame numbers | - | 18 bits ( |

| Address space | 4 GB | 1 GB |

Real-World Significance:

This 2-level scheme is very close to real x86-32:

- x86-32: 10 + 10 split (symmetric)

- Both provide massive memory savings for sparse address spaces

- Enables 32-bit computing with efficient page tables

Key Insight:

With 2-level page tables:

- Only allocate second-level tables as needed

- Most of the 4 GB virtual space has no second-level table (doesn’t consume memory)

- Process typically uses 20 KB of page tables (vs. 8 MB if single-level)

- This made 32-bit virtual memory practical in the 1990s-2000s

Problem 24: 32-bit Computer with Single-level Paging and 8KB Frames

Consider a 32-bit computer that has 1GB of physical memory. This machine employs single-level paging with 8KB frames.

(a) Show the parts of a virtual address, i.e., how many bits are used for offset, how many bits for indexing the page table?

LLM Solution

Virtual Address Breakdown:

Since the frame/page size is 8KB =

For a 32-bit architecture, the page number uses

Virtual Address Format:

The 19-bit page number is used to index into the page table, which contains

(b) How many physical frames does the machine have? How many bytes does a process page table occupy in memory?

LLM Solution

Number of Physical Frames: