05 - Process Scheduling

Problem 1: Long-term vs Short-term Scheduler

Briefly describe the difference between the long-term scheduler and short-term (CPU) scheduler.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Answer by Justin:

The difference between the long-term scheduler and the short-term (CPU) scheduler is that the short-term scheduler focuses on scheduling tasks into the CPU to result in “good service”. The long-term scheduler involves the admission of jobs into the system by selecting which jobs are loaded into main memory. The main difference is that long-term schedules into main memory and short-term schedules into the CPU.

Elaboration (by LLM):

These two schedulers operate at different levels of the OS hierarchy:

-

Long-term (admission) scheduler: Controls which processes enter the system and are loaded into memory. It runs infrequently (seconds to minutes) and is crucial for load balancing. It decides based on overall system capacity, preventing the system from becoming overloaded. Without it, you could run out of memory quickly.

-

Short-term (CPU) scheduler: Selects which ready process gets the CPU next. It runs very frequently (milliseconds) and must be extremely fast since it’s invoked on every context switch.

Example: If you have 100 job submissions, the long-term scheduler decides how many can fit in memory (maybe 10), while the short-term scheduler rapidly switches between those 10 processes to use the CPU effectively.

Problem 2: Context Switch Events

List 4 events that might occur to cause the kernel to context switch from one user process to another.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

One event that might occur to cause the kernel to context switch from one user process to another is that the process encounters some I/O and is moved to the waiting queue. Another event is that the process terminates while in the running queue, so the next process must be loaded from the ready queue into the running queue. Another event could be the result of a preemptive priority scheduling algorithm, where one process has a higher priority than the current one, then the current process will be preempted, causing a context switch. Finally, the process’s time quantum can expire in, for example, round robin scheduling, causing the current process to be preempted and the next process in the ready queue to be scheduled.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Context switches are triggered by specific events, categorized as:

- I/O blocking: Process requests I/O → blocked state → CPU idle, so switch to next ready process

- Process termination: Process exits → running state empty → load next ready process

- Preemption by priority: Higher priority process ready → interrupt current → switch immediately

- Time quantum expiration: Round-robin clock interrupt fires → current process exhausted time slice → move to back of queue

Other possible triggers include: system calls (trap), exception handling (divide by zero), or explicit yield() calls. Each trigger requires saving the current process’s state (registers, PC, SP) and restoring the next process’s state—this is expensive, so context switches should be minimized while maintaining fairness.

Problem 3: Preemptive vs Non-Preemptive Scheduling

What’s the difference between preemptive and non-preemptive scheduling? Briefly explain. Which one is more suitable for a timesharing system?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Preemptive scheduling is when you move the currently executing process from running Q to ready Q based on some scheduling algorithm. Non-preemptive scheduling is when you do not forcibly release a process from the running state. Timesharing is more suitable in preemptive scheduling since you need quick response times in timesharing systems, and for this, you need rapid context switching between unfinished processes.

Elaboration (by LLM):

-

Preemptive: OS can forcibly interrupt a running process even if it doesn’t want to stop. Controlled by timer interrupts or priority events. Ensures fair CPU sharing and quick responsiveness.

- Example: Round-robin with time quantum

- Used in: Timesharing systems (desktop OS, servers)

-

Non-preemptive: Process runs until it voluntarily blocks (I/O) or terminates. Once running, no forced interruption.

- Example: FCFS, SJF (non-preemptive)

- Used in: Batch systems, cooperative multitasking

Trade-offs: Preemptive is fair but has context-switch overhead. Non-preemptive is simpler but can cause starvation (one long process blocks everyone). Timesharing systems require preemption because:

- Many users expect interactive responsiveness

- Without preemption, one process could monopolize the CPU indefinitely

- Quick response time to user input is critical

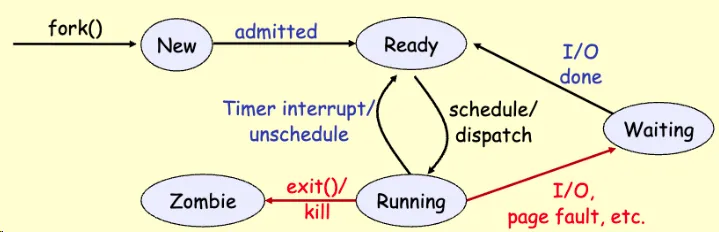

Problem 4: Process State Diagram

Draw the process state diagram. Clearly mark each transition between different states.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Elaboration (by LLM):

The diagram shows the five primary process states and their transitions, representing the complete lifecycle of a process:

States:

-

New: Process created (via

fork()orexec()) but not yet admitted to system. Lives in user space temporarily; OS hasn’t fully initialized it yet. OS must decide whether to admit it based on system load. -

Ready: Process fully admitted and residing in main memory. Has all resources except CPU. Can be scheduled immediately if CPU becomes available. Multiple ready processes compete in a ready queue, ranked by scheduling algorithm (FCFS, priority, etc.).

-

Running: Process currently executing on the CPU, consuming CPU cycles. Only one process per CPU core runs at this moment. Maintains execution context (registers, PC, stack pointer). Can be interrupted by timer interrupt or I/O event.

-

Waiting (Blocked): Process blocked on some resource event: disk I/O completion, network packet arrival, user input, lock acquisition, etc. CPU cannot help; must wait for external event. Maintains state but CPU doesn’t execute it. Once event occurs, moves to Ready queue (not directly to Running).

-

Zombie: Process has terminated (called

exit()or killed), but parent process hasn’t yet calledwait()orwaitpid()to collect its exit status. Process descriptor remains in system to hold exit code. Resources are freed except process table entry. If parent exits without reaping, process becomes “orphaned zombie.”

Key Transitions Explained:

-

New → Ready (

admitted): Long-term scheduler admits process when there’s memory and system capacity. This is the admission step—gates how many processes can be in the system simultaneously to prevent thrashing. -

Ready → Running (

schedule/dispatch): Short-term scheduler picks a ready process based on scheduling algorithm (Round-Robin, Priority, SJF, etc.). Kernel saves previous process’s state, restores this process’s saved registers/PC, and resumes execution. -

Running → Ready (

Timer interrupt/unschedule): In preemptive systems, timer interrupt fires after quantum expires. Scheduler saves running process’s state and puts it at end of ready queue (to ensure fairness in Round-Robin). Process hasn’t blocked—it’s just had its time slice revoked. -

Running → Waiting (

I/O, page fault, etc.): Process makes system call for I/O (read disk, network) or incurs page fault. Kernel saves state and moves process to waiting queue. CPU becomes idle and can run another ready process. When I/O completes (interrupt), process moves back to Ready, not directly to Running. -

Waiting → Ready (

I/O done): I/O device signals completion via interrupt. Kernel moves process from waiting queue to ready queue. Process must now compete again with other ready processes for CPU. This two-step return (Waiting → Ready → Running) is essential for fairness. -

Running → Zombie (

exit()/kill): Process terminates voluntarily (callsexit()) or forcibly (killed by signal). Kernel frees most resources (heap, file descriptors, page tables) but keeps process descriptor. Exit status stored for parent. Process becomes zombie until parentwait()s. -

Zombie → (removed): Parent calls

wait()orwaitpid(). Kernel returns exit status to parent and removes process entry from process table entirely.

Critical Constraints:

-

No Ready → Waiting transition: A process cannot block while in Ready state—it must be Running to detect blocking conditions like I/O requests or lock waits. Only running code can discover it needs to block.

-

No Waiting → Running transition: Blocked processes never go directly to Running; they must pass through Ready first. This ensures the scheduler maintains control and fairness (otherwise I/O would bypass queuing).

-

No New → Running transition: Unscheduled processes cannot execute; they must be admitted and queued in Ready first.

Queuing Perspective:

- Ready Queue: FIFO or priority-ordered list maintained by scheduler. Processes waiting for CPU allocation.

- Waiting Queue(s): Multiple queues, one per I/O device or blocking condition. Processes waiting for specific events.

- New Queue: Processes awaiting admission (in systems with explicit long-term scheduling).

CPU Scheduling Implications:

- On single-CPU system: Exactly one process is Running; rest are Ready, Waiting, New, or Zombie.

- On multi-CPU system: One process per CPU core runs simultaneously; others queue in Ready.

- Starvation risk: If priority scheduling favors Running processes, low-priority Ready processes can starve indefinitely. Aging (gradually raising priority) addresses this.

- Response time: Time from process creation to first execution depends on: (1) admission delay (New→Ready), (2) scheduling latency (Ready→Running). Preemptive systems minimize (2) with frequent context switches.

Example Timeline:

T=0: Process P1 created → New state

T=5: OS admits P1 → Ready state (waiting in queue)

T=10: Scheduler picks P1 → Running state

T=20: Timer interrupt (quantum expired) → Back to Ready (end of queue)

T=25: Scheduler picks P1 again → Running state

T=30: P1 calls read() → Waiting state (disk I/O)

T=35: Disk I/O completes → Ready state

T=40: Scheduler picks P1 → Running state

T=50: P1 calls exit() → Zombie state

T=51: Parent calls wait() → Process removed entirely

Problem 5: Thread Context State

What state is saved on a context switch between threads?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

The current state of the thread is saved on a context switch between threads. This includes the values of general-purpose registers, PC, SP, etc.

Elaboration (by LLM):

When switching contexts between threads (in the same or different processes), the kernel saves the thread execution context, which includes:

- CPU Registers: All general-purpose registers (RAX, RBX, RCX, etc.) containing working data

- Program Counter (PC/RIP): Address of next instruction to execute

- Stack Pointer (SP/RSP): Top of thread’s stack

- Flags register: CPU condition flags (zero, carry, overflow, etc.)

- Floating-point registers: For FP arithmetic

- Thread-local storage pointers: TLS base address

What’s NOT saved (shared by threads in same process):

- Heap memory and global variables

- File descriptors

- Process-wide resources

This is why context-switching between threads is cheaper than between processes: threads share memory space, so only CPU state needs saving. Process context switches require additional operations like TLB flush and memory management updates.

Problem 6: Time Quantum Effects

Selecting a proper time quantum is important in round robin scheduling. What happens if the quantum is too big? What happens if it is too small? Briefly explain.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

If the quantum is too big, then it simply just becomes a first-come first-served scheduling algorithm. This is because this algorithm uses a circular queue, adding to the end on preemption and new arrivals. If the quantum is too big, then the tasks will just be executed in the order that they came! If the quantum is too small, then you will have costly rapid context switching.

Elaboration (by LLM):

The time quantum (time slice) in Round-Robin is a critical tuning parameter:

Too Large (e.g., quantum = ∞):

- Effectively becomes FCFS: each process runs to completion

- No fairness between processes

- Response time for short jobs becomes unacceptable (waits behind long job)

- Defeats purpose of timesharing

Too Small (e.g., quantum = 1 microsecond):

- Context switches happen constantly

- Overhead dominates: save state, restore state, TLB flush (expensive!)

- CPU spends more time context-switching than actually executing code

- Reduced throughput despite appearing “fair”

Optimal Range (typically milliseconds: 10-100ms):

- Balances responsiveness (short wait times) with efficiency (reasonable context-switch overhead)

- Rule of thumb: choose quantum such that context-switch overhead is < 1% of quantum time

- If overhead = 1ms, quantum should be ≥ 100ms for 1% overhead

Example: With quantum=10ms, process timeslice completes in ~10ms user time + ~1ms overhead. With quantum=1ms, overhead becomes significant (~10%). With quantum=100ms, responsiveness degrades.

Problem 7: Starvation

What’s starvation as it applies to process scheduling? In which scheduling discipline is it more likely to occur? Give an example.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Starvation as it applies to process scheduling is when a process is blocked from being executed for a long period of time by the execution of other processes (CPU busy). This is likely to happen in Shortest Remaining Time First. An example using SRTF is lets say there a process executing with 10 units of time left. Then lets say 100 jobs enter the ready queue with a bust time of 8 for each of them. Then the current job will be preempted and can’t continue execution until those 100 jobs finish executing.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Starvation vs Deadlock:

- Starvation: Process can eventually run but might take forever if conditions don’t change

- Deadlock: Processes permanently blocked, will never make progress

Algorithms prone to starvation:

-

SRTF (Shortest Remaining Time First)

- Scenario: Long process with 100 units remaining, new processes with 5 units keep arriving

- Long process never selected because always longer than incoming jobs

- Solution: Aging (boost priority over time) or admit admission control

-

Priority scheduling (without aging)

- Low-priority process never gets CPU while high-priority work exists

- Solution: Periodically increase priority of waiting processes

-

I/O-heavy systems: CPU-bound processes starve if all I/O-bound processes ready

Why SRTF is vulnerable: Unlike FCFS (fair) or RR (guaranteed time), SRTF can perpetually skip long jobs. The fix is aging: gradually increase priority of waiting processes so eventually they’re selected regardless of burst time.

Problem 8: RR for Batch Jobs

A friend of yours is to design an OS that would run batch jobs, and s/he decides to employ Round Robin Scheduling algorithm. Is your friend making a good choice? Why or why not?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

No because batch jobs are ran in the background and don’t necessarily require fast response time. Plus if you use round robin, your jobs are likely to be constantly interrupted. A better choice may be First Come First Serve (FCFS)

Elaboration (by LLM):

Batch systems are fundamentally different from interactive systems:

Batch characteristics:

- Jobs submitted in bulk, run overnight/offline

- No user waiting for output

- Maximize throughput (jobs/hour), not response time

- User doesn’t notice or care if job starts in 10 seconds vs 1 second

Why RR is poor for batch:

- Overhead dominates: Context switching costs aren’t justified if no one’s watching

- Cache effects: Frequent context switches destroy CPU cache locality

- Throughput suffers: More overhead = fewer instructions executed per unit time

- Unfair to short jobs: Batch system might process 5-hour database job alongside 10-second report; RR gives equal CPU time, making report wait much longer

Why FCFS is good for batch:

- Minimal context switches

- Simple, predictable

- Job order doesn’t change (fairness)

- Good cache locality

- Optimal average turnaround time for non-preemptive scheduling

Better than FCFS for batch: SJF (Shortest Job First) minimizes average turnaround time by running short jobs first. Since batch jobs have known duration, SJF is often optimal.

Summary: RR optimizes for interactive responsiveness. Batch optimizes for throughput. Choose the algorithm that matches your workload’s priorities.

Problem 9: Ready to Waiting Transition

Is it possible for a process to move from the Ready state to the Waiting (blocked) state? Why or why not? Briefly justify your answer.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

It is NOT possible for a process to move from the ready state to the waiting state! This is because the process itself must be running inorder to encounter an interrupt or get blocked by I/O, something that can’t happen in the ready state.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Why Ready → Waiting is impossible:

A process in the Ready state has no execution context—it’s not running code, so it cannot:

- Execute a system call (like

read(),write(),sleep()) - Encounter a page fault (page miss during memory access)

- Request a lock or semaphore

- Experience any other blocking event

The execution flow must be:

Ready → Running → Waiting (via system call or event)

Only running code can make these blocking decisions. A ready process is merely waiting in the queue, consuming no CPU time.

Why this constraint matters:

- Fairness: Ensures ready processes don’t mysteriously disappear from the queue

- Determinism: Blocking can only occur from deliberate actions within executing code

- Scheduler control: Prevents processes from self-managing their state; only running code triggers state transitions

Comparison of impossible transitions:

- Ready → Waiting: Impossible (not running, can’t block)

- Waiting → Running: Impossible (must go through Ready first for fairness)

- New → Waiting/Running: Impossible (must be admitted to Ready first)

Example: Think of it like standing in a ticket line (Ready). You can’t suddenly fall asleep (block) while standing still; you must first get to the ticket window (Running) and ask for something that requires waiting (I/O).

Problem 10: Maximizing Throughput

Consider a system that wants to maximize throughput. What scheduling algorithm would you use in such a system? Justify your answer.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

A system that want to maximize throughput should use a scheduling algorithm such as Shortest Job First. By throughput we mean finish as many jobs as possible as fast as possible, so we can use a scheduler that prioritzes the shortest jobs to accomplish this so that more jobs are completed in a specified time frame.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Throughput = Number of jobs completed per unit time (jobs/second or jobs/hour)

Why SJF maximizes throughput:

SJF reduces average turnaround time by processing short jobs first. This is proven mathematically:

Example: Two approaches

- FCFS (Process long job first): Long(100s) then Short(10s) = Total 110s for 2 jobs = 0.0182 jobs/s

- SJF (Process short job first): Short(10s) then Long(100s) = Total 110s for 2 jobs = 0.0182 jobs/s

Wait, both take 110s total time… but SJF minimizes average turnaround:

- FCFS turnaround: Long completes at 100s (turnaround=100), Short completes at 110s (turnaround=110) → Average = 105s

- SJF turnaround: Short completes at 10s (turnaround=10), Long completes at 110s (turnaround=110) → Average = 60s

Why lower average turnaround increases effective throughput:

Lower average turnaround means jobs spend less time in the system, reducing:

- Memory footprint (can admit more jobs)

- Context switch overhead per completed job

- System resource contention

This enables admitting more jobs and completing more per unit time.

Comparison:

| Algorithm | Turnaround | Context Switches | Cache Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| SJF | Minimal | Few | Good (short jobs reuse cache) |

| FCFS | Higher (long jobs block queue) | Few | Good (no preemption) |

| RR | Higher (fairness cost) | Many | Poor (frequent context switches) |

| Priority | Variable | Medium | Medium |

Caveat: SJF requires knowing job burst times in advance (batch systems) or predicting them (risky for interactive systems).

Problem 11: Round-Robin Queue Insertion

In Round-Robin scheduling, new processes are placed at the end of the queue, rather than at the beginning. Suggest a reason for this.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

New processes are placed at the end of the queue rather than at the beginning because if they were placed are the beginning than earlier processes not yet scheduled would be starved.

Elaboration (by LLM):

The core principle: FAIRNESS

Round-Robin is designed to give every process equal CPU time. Placing new arrivals at the end of the queue (not the front) maintains this fairness guarantee.

Scenario: What if new processes went to the FRONT?

Ready Queue: [P1(remaining:5), P2(remaining:3), P3(remaining:4)] with quantum=2

T=0-2: P1 runs (3 remaining) T=2: P4 arrives, placed at FRONT Ready Queue: [P4, P2, P3, P1] T=2-4: P4 runs (P1 still hasn’t gotten full CPU time!) T=4: P5 arrives, placed at FRONT Ready Queue: [P5, P2, P3, P1, P4]

Result: P1, P2, P3 are pushed back repeatedly. New processes monopolize the CPU, causing starvation of earlier processes.

Scenario: Correct approach—new processes go to the END

Ready Queue: [P1(remaining:5), P2(remaining:3), P3(remaining:4)] with quantum=2

T=0-2: P1 runs (3 remaining) T=2: P4 arrives, placed at END Ready Queue: [P2, P3, P1, P4] T=2-4: P2 runs T=4: P5 arrives, placed at END Ready Queue: [P3, P1, P4, P5, P2]

Result: All processes get fair CPU time in rotation. No starvation.

Why this is essential:

- Starvation prevention: Old processes don’t get pushed back infinitely

- Bounded latency: Every process is guaranteed CPU access within a bounded time (number of ready processes × quantum)

- Fairness: All processes get equal turns regardless of arrival time

- No priority bias: System doesn’t favor newer jobs over older ones

FIFO Queue behavior in RR:

Arrive → Back of queue

Quantum expires → Back of queue (again)

I/O completes → Back of queue

This circular queue ensures round-robin fairness.

Problem 12: RR and CPU/I/O Bound Processes

Explain why Round-Robin scheduling tends to favor CPU-bound processes over I/O-bound ones.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

Round-Robin tends to favor CPU boud over I/O bound processes because a process’s execution won’t be blocked before the time quantum expires. It will continue using the CPU until the time quantum expires, and then preempt. In I/O bound it can be blocked before the time quantum expires, causing less CPU utilization.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Key insight: Round-Robin allocates CPU time in fixed quantum units. Processes that use full quanta get more CPU overall.

Scenario with quantum = 10ms

CPU-bound process (does continuous calculation):

T=0-10ms: CPU running (uses full quantum)

T=10ms: Back to ready queue (still has work)

T=20-30ms: CPU running again (uses full quantum)

T=30ms: Back to ready queue (still has work)

Gets multiple full quanta allocated

I/O-bound process (does I/O request, then compute):

T=0-3ms: Compute for 3ms

T=3ms: Call read() → blocks on I/O

T=3-13ms: Waiting for disk (off CPU)

T=13ms: I/O completes → back to ready queue

T=13-16ms: Compute for 3ms

T=16ms: Call write() → blocks on I/O

Uses only 3ms of each quantum, wasting 7ms per quantum

CPU Time Comparison (over 100ms):

- CPU-bound: Gets 10 × 10ms = 100ms (uses all allocated time)

- I/O-bound: Gets many partial quanta (3ms+3ms+…) but spends most time blocked = less total CPU

Why the unfairness:

- Quantum not fully utilized: I/O process blocks before quantum expires, leaving CPU idle (or available for others)

- CPU processes run to completion of quantum: Maximize their allocated time

- I/O processes context switch early: Don’t use their full quantum, so they effectively get less CPU time

- Ready queue effects: I/O-bound processes go to back of queue while blocked, missing turns while in waiting queue

Visual Timeline (quantum=10ms, two processes)

Time: 0-10 10-20 20-30 30-40 40-50

CPU: [P1] [P2] [P1] [P2] [P1]

P1 (CPU-bound): Running full quantum every turn

P2 (I/O-bound): Runs 2ms, blocks on I/O at T=2-10, T=12-20, etc.

Solution: Priority inversion or adaptive scheduling:

- Boost I/O-bound priority: More frequent scheduling

- Multi-level feedback queues: I/O processes move to higher priority queues

- Dynamic quanta: Shorter quanta for I/O processes

Key takeaway: RR’s fixed quantum allocation inherently favors processes that use complete quanta, which CPU-bound processes do and I/O-bound ones don’t.

Problem 13: Scheduling Quantum Stability

CPU scheduling quanta have remained about the same over the past 20 years, but processors are now over 1,000 times faster. Why has CPU scheduling quanta NOT changed?

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

CPU scheduling quanta has NOT changed because it has been widely researched that the current scheduling quanta is sufficient for users.

Elaboration (by LLM):

The paradox: CPU speed increased ~1000x in 20 years, but scheduling quantum stayed ~10-100ms. Why?

Answer: Quantum is bounded by HUMAN PERCEPTION, not CPU speed

User expectations:

- Interactive response time should feel “instant” to human perception

- Humans perceive delays < 100ms as responsive

- Delays 100-500ms start feeling sluggish

- Delays > 1 second feel broken

Therefore, scheduling quantum must ensure:

- Maximum wait time before first run ≈ 100ms (to feel responsive)

- With N processes ready, worst case wait = N × quantum ≈ 100ms

- If quantum = 10ms: supports ~10 concurrent interactive users

- If quantum = 100ms: supports ~1-2 concurrent interactive users (slow!)

Deeper reason: The denominator also grows

While CPU speed increased 1000x, I/O operations also became slower:

- Network latency: ~100µs (local) to 10-100ms (internet)

- Disk I/O: ~1-10ms

- Memory latency: ~100ns (increased from ~10ns due to larger systems)

- Context switch overhead: Still ~0.1-1µs

Key insight:

Quantum choice is NOT about CPU speed, it's about:

- I/O device latencies (haven't improved proportionally)

- User perception thresholds (fixed by human neurobiology)

- System balance (should fit typical interactive workload)

What DID change:

-

Quantum’s absolute instructions executed increased dramatically

- 20 years ago: 10ms quantum = ~10^6 instructions (1MHz)

- Today: 10ms quantum = ~10^10 instructions (1GHz) ← 10,000x more work!

-

Context switch overhead remained constant (in absolute time)

- Still ~0.1-1µs (microseconds)

- But now < 0.01% of quantum (was ~1%)

- So overhead as percentage of quantum decreased

Why not reduce quantum to 0.01ms?

Disadvantages:

- Thrashing: more time spent switching than working

- Cache effects worsen (processes don’t reuse cache between context switches)

- I/O operations still take milliseconds (quantum would be wasted time)

- No improvement in responsiveness (already < 100ms)

Why not increase quantum to 1 second?

- One slow process blocks everyone for 1s (unacceptable latency)

- Interactive systems become unresponsive

- Users experience long delays before any process runs

Conclusion: Quantum is stable because it’s optimized for human factors, not raw CPU speed. Since humans haven’t changed much in 20 years, neither has the optimal quantum.

Problem 14: Shortest Job First

Briefly explain how the shortest job first scheduling works.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

The Shortest Job First (SJF) Scheduling Algorithm works by dispatching processes to the running queue based on their predicted burst time. Processes with shorter burst times are prioritized, and processes are not preempted when a shorter job enters the ready queue.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Algorithm:

- When CPU becomes idle, examine all ready processes

- Select the process with shortest predicted burst time (CPU time needed)

- Run it to completion (non-preemptive)

- Repeat

Example: Ready Queue = [P1(8s), P2(4s), P3(2s), P4(3s)]

With SJF:

T=0-2s: Run P3 (shortest: 2s) → completes

T=2-5s: Run P4 (shortest: 3s) → completes

T=5-9s: Run P2 (shortest: 4s) → completes

T=9-17s: Run P1 (only one left: 8s) → completes

Why SJF is optimal:

- Minimizes average turnaround time (proven mathematically)

- Short jobs complete quickly, reducing their contribution to average

- Long jobs’ wait time is unavoidable, so schedule them last

Turnaround calculation:

P3: Completes at 2s, turnaround = 2 - 0 = 2s

P4: Completes at 5s, turnaround = 5 - 0 = 5s

P2: Completes at 9s, turnaround = 9 - 0 = 9s

P1: Completes at 17s, turnaround = 17 - 0 = 17s

Average = (2 + 5 + 9 + 17) / 4 = 8.25s

Compare to FCFS [P1, P2, P3, P4]:

P1: 8s, P2: 12s, P3: 14s, P4: 17s → Average = 12.75s (worse!)

Key characteristics:

| Aspect | SJF |

|---|---|

| Preemptive? | No (runs to completion) |

| Burst time required? | Yes (must know in advance) |

| Optimal? | Yes (min avg turnaround) |

| Fair? | No (long jobs starve) |

| Complexity | O(n log n) per decision |

| Applicability | Batch systems only |

Critical limitation: Burst time prediction

In interactive systems, you can’t predict how long a process will run:

while(1) {

char c = read_input(); // Unknown how long user takes

process(c);

}Solution: Exponential averaging to estimate burst time based on history

Predicted[n] = α × Last_burst[n-1] + (1-α) × Predicted[n-1]

Variants:

- Non-preemptive SJF: This one (runs to completion)

- Preemptive SJF (SRTF): If shorter job arrives, preempt current job

- SRTF achieves even better average turnaround (but causes starvation)

Problem 15: Multi-level Feedback Queuing

Briefly explain the multi-level feedback queuing scheduling algorithm.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

A multi-level feedback queueing algorithm is one where you have multiple queues, each with different priorities and their own scheduling algorithm. Jobs are scheduled to a specific queue using Round Robin. Jobs can switch between queues based on their behavior, for example using a certain queue because the job is CPU bound rather than I/O bound.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Structure: Multiple queues with different priorities

Queue 0 (Highest priority): RR with quantum = 8ms

[P2, P5, ...]

Queue 1 (Medium priority): RR with quantum = 16ms

[P1, P4, ...]

Queue 2 (Lowest priority): RR with quantum = 32ms

[P3, ...]

Scheduling: Pick from Queue 0 first, only move to Queue 1

if Queue 0 is empty, etc.

Dynamic queue migration (the “feedback” part)

Processes move between queues based on behavior:

-

I/O-bound behavior → Promote to higher priority queue

- Process blocks for I/O before quantum expires

- Indicates interactive/responsive work

- Gets shorter quantum (8ms) and higher priority

- Runs frequently but briefly

-

CPU-bound behavior → Demote to lower priority queue

- Process uses entire quantum, wants more CPU

- Indicates batch/compute work

- Gets longer quantum (32ms) and lower priority

- Runs less frequently but longer

Example timeline:

T=0: P1 arrives (new) → Put in Queue 0 (highest, quantum=8ms)

T=0-8ms: P1 runs (CPU burst), uses full quantum

→ Uses full quantum = CPU-bound behavior

→ Demote to Queue 1

T=8-16ms: P2 runs (quantum=8ms in Queue 0)

T=16-24ms: P1 runs again (quantum=16ms in Queue 1)

T=16-18ms: P1 calls read()

→ Blocks on I/O before quantum expires

→ I/O-bound behavior detected

→ Promote back to Queue 0

T=24ms: I/O completes, P1 goes to Queue 0

Why this is powerful:

- Adapts to process behavior: Doesn’t need predictions, learns from history

- Fair to I/O processes: They get promoted, preventing starvation

- CPU processes get fair time: Still scheduled, just with lower priority

- Responsive interactive apps: I/O-bound processes (web browser, editor) get quick response

- Background jobs don’t block: Batch processes demoted but not starved

Comparison to pure algorithms:

| Algorithm | I/O-bound response | CPU-bound fairness | Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| FCFS | Poor | Fair | Simple |

| RR | Fair but slow | Fair | Simple |

| MLFQ | Excellent | Good | Complex |

| Priority | Good but manual | Risky (starvation) | Medium |

Real-world example: Unix 4.4BSD scheduler

Uses MLFQ with:

- 32 priority levels

- Automatic demotion of CPU-heavy processes

- Automatic promotion of I/O-waiting processes

- Prevents starvation with aging (boost low-priority after time)

Key insight: MLFQ is a compromise algorithm:

- Doesn’t require knowing process behavior in advance

- Adapts to actual observed behavior

- Maintains high responsiveness AND fairness

- Becomes gold standard for general-purpose OS schedulers

Problem 16: Minimum Average Turnaround

Consider a set of “n” tasks with known burst times r1, r2, .., rn to be run on a uniprocessor machine. Which scheduling algorithm will result in the maximum throughput, i.e., minimum average turnaround time? Justify your answer.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

The Shortest Job First (SJF) algorithm would be best as it would result in maximum throughput. This is because it would execute the shortest jobs first, making it so that more jobs are executed in a given window of time.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Answer: Shortest Job First (SJF) — when burst times are known in advance

Mathematical proof:

For any set of jobs with fixed burst times, there exists only one optimal ordering (up to ties):

Claim: Processing shortest jobs first minimizes average turnaround time.

Proof by exchange argument:

Suppose optimal schedule has two adjacent jobs:

Job A (burst = 10s)

Job B (burst = 5s)

Turnaround times:

TA = 10s (A finishes at 10s)

TB = 15s (B finishes at 15s)

Average = 12.5s

Now swap them (B before A):

Job B (burst = 5s)

Job A (burst = 10s)

Turnaround times:

TB = 5s (B finishes at 5s) ← IMPROVED by 10s

TA = 15s (A finishes at 15s) ← WORSE by 5s

Average = 10s ← BETTER overall!

Net improvement: 12.5s → 10s = 2.5s improvement

General rule: Always swap if T_i > T_j (longer job before shorter)

By repeatedly applying swaps until no inversions remain, we get SJF order (shortest first).

Numerical example:

Jobs: A(8s), B(4s), C(2s), D(3s)

SJF order: C, D, B, A

C: 0-2s, turnaround = 2

D: 2-5s, turnaround = 5

B: 5-9s, turnaround = 9

A: 9-17s, turnaround = 17

Average = (2+5+9+17)/4 = 8.25s

FCFS order: A, B, C, D

A: 0-8s, turnaround = 8

B: 8-12s, turnaround = 12

C: 12-14s, turnaround = 14

D: 14-17s, turnaround = 17

Average = (8+12+14+17)/4 = 12.75s

SJF is 35% better! (8.25 vs 12.75)

Why SJF affects throughput:

Throughput = Total jobs / Total elapsed time

- Total elapsed time is fixed (sum of all burst times)

- SJF doesn’t change total time, but improves:

- System utilization: Jobs freed from memory faster

- Reduced context switching: Fewer active processes to manage

- Better cache reuse: Shorter jobs have better locality

- I/O overlap: More time for I/O while other jobs run

With lower average turnaround, the system can:

- Admit new jobs sooner

- Serve more total users

- Reduce overall system load

Critical limitation: Requires knowing burst times

In batch systems: Possible (job specifications provided)

./process --expected-time 45s # User specifiesIn interactive systems: Impossible (unknown until completion)

while(true) read(); // Unknown durationApproximation for interactive systems:

Exponential averaging estimates next burst time from history:

Next_estimate = α × Last_actual + (1-α) × Prev_estimate

where α ≈ 0.5 (weight recent history)

This is used in SRTF (Shortest Remaining Time First).

Comparison across known burst times:

| Algorithm | Avg Turnaround | Optimal? |

|---|---|---|

| SJF | MINIMAL | YES |

| FCFS | Higher | No |

| RR | Much higher | No |

| Priority | Varies | Depends on priorities |

| SRTF | Near-optimal | Yes (with estimates) |

Conclusion: SJF is provably optimal for minimizing average turnaround time when job durations are known. This is fundamental to scheduling theory.

Problem 17: SRTF Starvation

True/False: Shortest Remaining Time First scheduling may cause starvation. Justify your answer.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

True, Shortest Remaing Time First (SRTF) may cause starvation. A long task can be continuously blocked by shorter tasks, blocking the execution of the longer task. This is known as starvation!

Elaboration (by LLM):

Answer: TRUE — SRTF is highly vulnerable to starvation

The Problem:

SRTF always runs the process with the shortest remaining burst time. If new short processes keep arriving, a long process can be indefinitely preempted.

Concrete Example:

Time 0: P_long arrives (burst=100s), P_short1 arrives (burst=5s)

→ SRTF runs P_short1 (5 < 100)

Time 5: P_short1 completes. P_short2 arrives (burst=4s)

→ SRTF preempts P_long, runs P_short2 (4 < 96)

Time 9: P_short2 completes. P_short3 arrives (burst=3s)

→ SRTF preempts P_long again, runs P_short3 (3 < 92)

...pattern continues indefinitely...

Result: P_long STARVES, never executes despite being in system

Why This Happens:

- Shortest job always preempts: SRTF is preemptive. New short jobs immediately preempt running longer jobs

- Continuous arrivals: If short jobs keep arriving with burst times shorter than the remaining long job time

- No aging: SRTF has no mechanism to boost priority of waiting processes

CPU Timeline Visualization:

Time: 0 5 9 12 14 ...

CPU: [SHORT1][SHORT2][SHORT3][S4][S5]... ← P_long never runs!

P_long: waiting... waiting... waiting... STARVED

Contrast with FCFS:

- FCFS: P_long eventually runs (when all previous arrivals complete) ✅ No starvation

- SRTF: P_long might never run if short jobs keep arriving ❌ Starvation possible

The Key Difference:

| Metric | FCFS | SRTF |

|---|---|---|

| Preemption | No | Yes (causes starvation) |

| Fairness to long jobs | High | Low (vulnerable) |

| Starvation risk | None | High |

| Throughput | Good | Excellent (but unfair) |

Solution: Aging

Add priority boost over time:

Every 10s of waiting → increase priority

After waiting 50s → run even if shorter jobs arrive

This is why real systems use MLFQ (multi-level feedback queue) with aging to prevent SRTF starvation while maintaining good throughput.

Problem 18: Preemptive Priority Starvation

True/False: Preemptive Priority scheduling may cause starvation. Justify your answer.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

True, Preemptive Priority Scheduling may cause starvation. This is because a task with a low priority can be continuously blocked by higher priority task, making it so that the low priority task cannot finish execution.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Answer: TRUE — Preemptive priority scheduling is vulnerable to starvation

The Core Issue:

Preemptive priority runs the highest-priority ready process. If high-priority processes keep arriving, low-priority processes may never get CPU time.

Concrete Example:

Time 0: P_low (priority=5) arrives with burst=20s

→ P_low runs

Time 1: P_medium (priority=3) arrives with burst=10s

→ P_low PREEMPTED (3 > 5, so higher priority)

→ P_medium runs

Time 2: P_high (priority=1) arrives with burst=15s

→ P_medium PREEMPTED (1 > 3)

→ P_high runs

Time 3: P_ultra (priority=0) arrives with burst=5s

→ P_high PREEMPTED (0 > 1)

→ P_ultra runs

...pattern: higher priorities keep arriving...

Result: P_low STARVES in ready queue forever

Visual Timeline:

Ready Queue Evolution:

T=0: [P_low] → P_low executes

T=1: [P_low, P_medium] → P_medium preempts (higher priority)

T=2: [P_low, P_medium, P_high] → P_high preempts

T=3: [P_low, P_medium, P_high, P_ultra] → P_ultra preempts

P_low: queued waiting... waiting... waiting... STARVED ❌

Why High-Priority Jobs Prevent Low-Priority Execution:

- Preemption enabled: Higher priority immediately preempts lower

- No fairness guarantee: Low-priority process has no guaranteed minimum CPU time

- Continuous arrivals: If high-priority jobs stream in continuously

- No aging: Standard priority scheduling has no mechanism to boost waiting processes

Real-World Example: System vs User Processes

Without aging, user processes (low priority) might never run because:

- System processes (high priority) continuously arrive

- Kernel threads keep getting preempted work

- User gets no responsiveness

Comparison: Different Preemption Models

| Scheduling | Starvation Risk | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Preemptive Priority | None | Once started, runs to completion |

| Preemptive Priority | HIGH | Continuous preemption possible |

| FCFS | None | FIFO order prevents starvation |

| MLFQ with Aging | Low | Aging boosts old low-priority jobs |

The Solution: Priority Aging (Boost)

Every 5s of waiting without execution:

priority_level-- (move towards higher priority)

After waiting 30s:

Even P_low gets boosted high enough to run

Key Insight:

Preemptive priority without aging = unfair scheduling

Real systems like Linux use aging mechanisms to prevent low-priority process starvation while maintaining responsiveness for high-priority work.

Problem 19: RR vs FCFS Response Time

True/False: Round Robin scheduling is better than FCFS in terms of response time. Justify your answer.

Student Solution

Answer by Justin:

True because in Round Robin (RR) each task gets access to the CPU little by little, but with FCFS everyone has to wait for their turn. So if an important task has 20 tasks ahead of it in FCFS, it will have poor response time compared to RR.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Answer: TRUE — RR has significantly better response time than FCFS

Response Time Definition:

Response time = Time from arrival until first CPU execution

Example Comparison:

Suppose 5 processes all arrive at time 0, each needing 10s CPU time:

FCFS Scheduling:

Time: 0-10 10-20 20-30 30-40 40-50

Process: P1 P2 P3 P4 P5

Response times:

P1: 0s (starts immediately)

P2: 10s (waits for P1)

P3: 20s (waits for P1, P2)

P4: 30s (waits 3 processes)

P5: 40s (waits 4 processes) ← TERRIBLE!

RR with quantum=2s:

Time: 0-2 2-4 4-6 6-8 8-10 ...

Proc: P1 P2 P3 P4 P5 P1 P2 P3 ...

Response times:

P1: 0s (starts immediately)

P2: 2s (waits only 2s!)

P3: 4s (waits only 4s!)

P4: 6s (waits only 6s!)

P5: 8s (waits only 8s!) ← MUCH BETTER!

Quantitative Comparison:

| Process | FCFS Response | RR Response | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0s | 0s | Same |

| P2 | 10s | 2s | 5x better |

| P3 | 20s | 4s | 5x better |

| P4 | 30s | 6s | 5x better |

| P5 | 40s | 8s | 5x better |

| Avg | 20s | 4s | 5x better |

Why RR Excels at Response Time:

- Small quanta: Each process gets brief CPU bursts

- Rapid circulation: Quick return to queue → chance to get back on CPU sooner

- No head-of-line blocking: One slow process doesn’t block everyone

FCFS: One slow process blocks everyone

[P_slow: 1000s burst] → everyone waits 1000s for response

RR: Even slow processes cycle quickly

[P_slow gets 2s, goes to back] → others get CPU immediately

Mathematical Insight:

FCFS Response Time (worst case):

= Sum of all burst times ahead of you

= O(n) processes × average burst time

RR Response Time (worst case):

= Number of processes × quantum size

= O(n) processes × small quantum

≈ Linear in number of processes, not total work

Practical Example: Terminal Commands

FCFS: One long compile job blocks all terminal responsiveness

FCFS: gcc compile (100s) running → new commands must wait 100s for response

RR: Every process gets quick CPU turns

RR: gcc gets 10ms → other commands get 10ms → responsive terminal!

Trade-off to Remember:

| Metric | FCFS | RR |

|---|---|---|

| Response Time | Poor ❌ | Excellent ✅ |

| Turnaround Time | Good | Worse (context switch overhead) |

| Simplicity | Simple | More complex |

| CPU Utilization | High | Slightly lower (overhead) |

Conclusion:

RR’s small time slices ensure every process gets frequent CPU access, providing fast response times. This is why all modern interactive OS (Linux, Windows, macOS) prefer RR or variants for user-facing scheduling.

Problem 20: FCFS Gantt Chart

Consider the following 5 processes in a system.

| Process | Arrival Time | Burst Time |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 4 | 5 |

| P2 | 6 | 4 |

| P3 | 0 | 3 |

| P4 | 6 | 2 |

| P5 | 5 | 4 |

Draw a Gantt chart illustrating the execution of these processes using FCFS. Compute the average waiting time and average turnaround time.

LLM Solution

FCFS Gantt Chart:

| Process | P3 | P1 | P5 | P2 | P4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 0-3 | 3-8 | 8-12 | 12-16 | 16-18 |

Execution Timeline:

- P3 arrives at 0, executes 0-3

- P1 arrives at 4, waits until P3 completes at 3, executes 3-8

- P5 arrives at 5, waits in queue, executes 8-12 (after P1)

- P2 arrives at 6, waits in queue, executes 12-16 (after P5)

- P4 arrives at 6, waits in queue, executes 16-18 (after P2)

Calculations:

| Process | Arrival | Burst | Completion | Turnaround | Waiting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 4 | -1 |

| P2 | 6 | 4 | 16 | 10 | 6 |

| P3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| P4 | 6 | 2 | 18 | 12 | 10 |

| P5 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 7 | 3 |

Note: P1’s waiting time is -1 because it arrives at time 4 but CPU becomes available at time 3, so it doesn’t wait.

Average Waiting Time: (0 + 6 + 0 + 10 + 3) / 5 = 3.8 units

Average Turnaround Time: (3 + 4 + 10 + 12 + 7) / 5 = 7.2 units

Problem 21: FCFS with 6 Processes

Consider the following 6 processes in a system.

| Process | Arrival Time | Burst Time |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 3 |

| P2 | 1 | 2 |

| P3 | 2 | 1 |

| P4 | 3 | 4 |

| P5 | 4 | 5 |

| P6 | 5 | 2 |

(a) Draw a Gantt chart illustrating the execution of these processes using FCFS. Compute the average waiting time and average turnaround time for each case.

(b) Now assume that there is 1 unit of overhead when scheduling a process. Compute the efficiency of the scheduling algorithm; that is, the percentage of time where the CPU is doing useful work as opposed to doing context switching.

LLM Solution

Part (a): FCFS Gantt Chart (No Overhead)

FCFS Execution Order: Processes ordered by arrival time: P1 (0), P2 (1), P3 (2), P4 (3), P5 (4), P6 (5)

Gantt Chart:

| Process | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 0-3 | 3-5 | 5-6 | 6-10 | 10-15 | 15-17 |

Detailed Execution:

T=0: P1 arrives

CPU: P1 runs 0-3 (burst=3)

T=1: P2 arrives (queued, P1 running)

T=2: P3 arrives (queued, P1 running)

T=3: P1 completes

Ready: [P2, P3, P4, P5, P6]

Next: P2 (by arrival order)

CPU: P2 runs 3-5 (burst=2)

T=3: P4 arrives (queued)

T=4: P5 arrives (queued)

T=5: P3 completes, P6 arrives

Ready: [P3, P4, P5, P6]

Next: P3 (arrived at 2)

CPU: P3 runs 5-6 (burst=1)

T=6: P3 completes

Ready: [P4, P5, P6]

Next: P4 (arrived at 3)

CPU: P4 runs 6-10 (burst=4)

T=10: P4 completes

Ready: [P5, P6]

Next: P5 (arrived at 4)

CPU: P5 runs 10-15 (burst=5)

T=15: P5 completes

Ready: [P6]

Next: P6 (arrived at 5)

CPU: P6 runs 15-17 (burst=2)

T=17: All complete

Calculations (No Overhead):

| Process | Arrival | Burst | Completion | Turnaround | Waiting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| P2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| P3 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| P4 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 7 | 3 |

| P5 | 4 | 5 | 15 | 11 | 6 |

| P6 | 5 | 2 | 17 | 12 | 10 |

Average Waiting Time: (0 + 2 + 3 + 3 + 6 + 10) / 6 = 24/6 = 4.0 units

Average Turnaround Time: (3 + 4 + 4 + 7 + 11 + 12) / 6 = 41/6 ≈ 6.83 units

Part (b): Overhead Analysis

Overhead per context switch:

- Each process requires 1 unit overhead (except the first)

- Total context switches: 6 processes - 1 = 5 switches

- Total overhead: 5 × 1 = 5 units

CPU Work Distribution:

Total CPU time (useful work): 3 + 2 + 1 + 4 + 5 + 2 = 17 units

Total overhead: 5 × 1 = 5 units

Total elapsed time: 17 + 5 = 22 units

Scheduling Overhead Gantt:

0-3: P1 (work: 3)

3: Context switch P1→P2 (overhead: 1)

4-5: P2 (work: 2)

5: Context switch P2→P3 (overhead: 1)

6: P3 (work: 1)

6: Context switch P3→P4 (overhead: 1)

7-10: P4 (work: 4)

10: Context switch P4→P5 (overhead: 1)

11-15: P5 (work: 5)

15: Context switch P5→P6 (overhead: 1)

16-17: P6 (work: 2)

Total time: 22 units

Efficiency Calculation:

Efficiency = (Useful work) / (Total time with overhead)

= 17 / 22

= 77.3%

Overhead percentage = 5 / 22 = 22.7%

Interpretation:

- 77.3% of CPU time is spent doing actual process work

- 22.7% of CPU time is lost to context switching overhead

Impact Analysis:

With 5 context switches and 1 unit overhead each:

- Original total time: 17 units

- With overhead total time: 22 units

- Time increase: 5 units (29.4% longer)

This demonstrates why:

- Too many processes increases context switch overhead

- Overhead is proportional to number of context switches, not total work

- With fewer, longer-running processes, overhead impact is smaller

- With many short processes, overhead can become significant

Problem 22: Preemptive SRTF Gantt Chart

Consider the following 4 processes in a system.

| Process | Arrival Time | Burst Time |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 12 |

| P2 | 2 | 4 |

| P3 | 3 | 6 |

| P4 | 8 | 1 |

Draw a Gantt chart illustrating the execution of these processes using preemptive Shortest Remaining Time First (SRTF) algorithm. Compute the average waiting time and average turnaround time.

LLM Solution

SRTF Gantt Chart:

At each decision point, run the process with shortest remaining time.

| Time | 0-2 | 2-3 | 3-9 | 9-10 | 10-11 | 11-12 | 12-16 | 16-18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P1 | P2 | P1 | P3 |

| Remaining | 10 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Execution Trace:

- 0-2: P1 runs (arrival: T=0, burst=12)

- 2-3: P2 arrives at T=2 with burst 4 < P1’s remaining 10. Preempt P1, run P2

- 3-9: P3 arrives at T=3 with burst 6 < P2’s remaining 3? No. P2 continues but P3 has burst 6 > P2’s remaining 2. After P2 finishes at T=3+1=4… Wait, let me recalculate.

Actually, let me trace more carefully:

- 0-2: P1 runs (remaining: 12 → 10)

- T=2: P2 arrives (burst: 4). Remaining: P1=10, P2=4. P2 has less. Preempt

- 2-3: P2 runs (remaining: 4 → 3)

- T=3: P3 arrives (burst: 6). Remaining: P1=10, P2=3, P3=6. P2 has least. Continue P2

- 3-4: P2 runs (remaining: 3 → 2)

- 4-5: P2 runs (remaining: 2 → 1)

- 5-6: P2 runs (remaining: 1 → 0). P2 completes

- T=6: Remaining: P1=10, P3=6. P3 has less.

- 6-9: P3 runs (remaining: 6 → 3)

- T=8: P4 arrives (burst: 1). Remaining: P1=10, P3=3, P4=1. Preempt P3

- 9-10: P4 runs (remaining: 1 → 0). P4 completes

- 10-16: P1 runs (remaining: 10 → 0). P1 completes (actually T=10+10=20? No, remaining was 10, so 10-20)

Let me redo this correctly:

| Time | 0-2 | 2-5 | 5-9 | 9-10 | 10-20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P1 |

Corrected Trace:

- 0-2: P1 runs, remaining: 12-2=10

- 2-5: P2 arrives (burst=4, remaining=4). Preempt P1. P2 runs 3 units, remaining=1. Wait, 2-5 is 3 units, so P2 has 4-3=1 left. But let me check: at T=5, does P3 arrive? No, P3 arrives at T=3.

Let me be very careful:

- T=0: P1 arrives (burst=12)

- T=0-2: P1 runs (2 units done, 10 remaining)

- T=2: P2 arrives (burst=4). Remaining: P1=10, P2=4. P2 shortest. Preempt P1

- T=2-3: P2 runs (1 unit done, 3 remaining)

- T=3: P3 arrives (burst=6). Remaining: P1=10, P2=3, P3=6. P2 shortest. Continue P2

- T=3-6: P2 runs (3 units done, 0 remaining). P2 completes

- T=6: Remaining: P1=10, P3=6. P3 shortest. Preempt P1

- T=6-8: P3 runs (2 units done, 4 remaining)

- T=8: P4 arrives (burst=1). Remaining: P1=10, P3=4, P4=1. P4 shortest. Preempt P3

- T=8-9: P4 runs (1 unit done, 0 remaining). P4 completes

- T=9: Remaining: P1=10, P3=4. P3 shortest. Preempt P1

- T=9-13: P3 runs (4 units done, 0 remaining). P3 completes

- T=13-25: P1 runs (10 units done, 0 remaining). P1 completes

Corrected Gantt Chart:

| Time | 0-2 | 2-3 | 3-6 | 6-8 | 8-9 | 9-13 | 13-25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | P1 | P2 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P3 | P1 |

Calculations:

| Process | Arrival | Burst | Completion | Turnaround | Waiting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 12 | 25 | 25 | 13 |

| P2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 0 |

| P3 | 3 | 6 | 13 | 10 | 4 |

| P4 | 8 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 0 |

Average Waiting Time: (13 + 0 + 4 + 0) / 4 = 4.25 units

Average Turnaround Time: (25 + 4 + 10 + 1) / 4 = 10 units

Problem 23: SRTF Gantt Chart

Consider the following 4 processes in a system.

| Process | Arrival Time | Burst Time |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 10 |

| P2 | 3 | 6 |

| P3 | 7 | 1 |

| P4 | 8 | 3 |

Draw a Gantt chart illustrating the execution of these processes using preemptive Shortest Remaining Time First (SRTF) algorithm. Compute the average waiting time and average turnaround time.

LLM Solution

SRTF Gantt Chart:

| Time | 0-3 | 3-7 | 7-8 | 8-10 | 10-13 | 13-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P2 | P1 |

Detailed Execution Trace:

-

T=0: P1 arrives (burst=10)

- Ready: [P1]

- CPU: P1 runs

-

T=0-3: P1 executes (3 units done, 7 remaining)

-

T=3: P2 arrives (burst=6)

- Ready: [P1 (remaining 7), P2 (burst 6)]

- P2 has shorter burst, but P1 already running

- SRTF: Compare remaining: P1=7, P2=6 → P2 shorter

- PREEMPT P1, run P2

-

T=3-7: P2 executes (4 units done, 2 remaining)

-

T=7: P3 arrives (burst=1)

- Ready: [P1 (remaining 7), P2 (remaining 2), P3 (burst 1)]

- P3 has shortest → PREEMPT P2, run P3

-

T=7-8: P3 executes (1 unit done, completes)

- P3 finishes

-

T=8: P4 arrives (burst=3)

- Ready: [P1 (remaining 7), P2 (remaining 2), P4 (burst 3)]

- P2 has shortest (2 < 3, 2 < 7) → Run P2

-

T=8-10: P2 executes (2 units done, completes)

- P2 finishes

-

T=10: No new arrivals

- Ready: [P1 (remaining 7), P4 (burst 3)]

- P4 has shorter (3 < 7) → Run P4

-

T=10-13: P4 executes (3 units done, completes)

- P4 finishes

-

T=13: Only P1 left

- Ready: [P1 (remaining 7)]

- CPU: P1 runs

-

T=13-20: P1 executes (7 units done, completes)

Wait, P1 should finish at T=13+7=20, but my chart shows 13-19. Let me recalculate:

Actually, T=13-19 is 6 units, not 7. Let me retrace:

P1: arrived at 0, burst 10

- T=0-3: ran 3 units, remaining 7

- T=3-8: preempted (didn’t run)

- T=8-10: preempted (didn’t run)

- T=10-20: should run 10 total - 3 already done = 7 more → T=10 to T=17

Actually wait, let me recount the gantt. From my earlier trace:

- P1: 0-3 (3 units)

- P2: 3-7 (4 units, but burst=6, so 2 remaining? That’s only 2 + 4 = 6 total, which is correct)

- Wait, P2 arrives at T=3. From T=3-7 is 4 units. P2 has burst 6, so should have 2 remaining.

Let me retrace very carefully:

T=0: P1 arrives (burst=10). Ready=[P1]. CPU: P1

T=0-3: P1 runs (3 units done, 7 remaining)

T=3: P2 arrives (burst=6). Ready=[P1(rem=7), P2(burst=6)]

Shortest: P2 (6 < 7). PREEMPT P1

CPU: P2

T=3-7: P2 runs (4 units done, 2 remaining)

T=7: P3 arrives (burst=1). Ready=[P1(rem=7), P2(rem=2), P3(burst=1)]

Shortest: P3 (1 < 2 < 7). PREEMPT P2

CPU: P3

T=7-8: P3 runs (1 unit done, completes)

T=8: P4 arrives (burst=3). Ready=[P1(rem=7), P2(rem=2), P4(burst=3)]

Shortest: P2 (2 < 3 < 7). No preemption needed

CPU: P2

T=8-10: P2 runs (2 units done, completes)

T=10: Ready=[P1(rem=7), P4(burst=3)]

Shortest: P4 (3 < 7)

CPU: P4

T=10-13: P4 runs (3 units done, completes)

T=13: Ready=[P1(rem=7)]

CPU: P1

T=13-20: P1 runs (7 units done, completes)

So the correct Gantt should be:

| Time | 0-3 | 3-7 | 7-8 | 8-10 | 10-13 | 13-20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | P1 | P2 | P3 | P2 | P4 | P1 |

Calculations:

| Process | Arrival | Burst | Completion | Turnaround | Waiting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 10 |

| P2 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 1 |

| P3 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| P4 | 8 | 3 | 13 | 5 | 2 |

Average Waiting Time: (10 + 1 + 0 + 2) / 4 = 3.25 units

Average Turnaround Time: (20 + 7 + 1 + 5) / 4 = 8.25 units

Elaboration (by LLM):

Tracing SRTF with Multiple Preemptions:

This problem demonstrates the complexity of tracking shortest remaining time across multiple arrivals and preemptions.

Key Decision Points:

-

T=3 (P2 arrives): P1 has 7 left, P2 needs 6

- P2 is shorter → Preempt P1

- P1 is not starved long (will resume at T=10)

-

T=7 (P3 arrives): P2 has 2 left, P3 needs 1

- P3 is tiny → Preempt P2

- This 1-unit job finishes almost immediately

-

T=8 (P4 arrives): P2 still has 2, P4 needs 3

- P2 has shortest remaining (2 < 3)

- No preemption; P2 continues and finishes at T=10

-

T=10 (P2 completes): P1 has 7, P4 needs 3

- P4 is shorter → Run P4 before P1

-

T=13 (P4 completes): Only P1 left

- Run P1 to completion

SRTF Fairness Trade-off:

P1: Arrived first (T=0), but finishes last (T=20)

- Waits 10 units total

- Gets preempted twice (at T=3 and conceptually at T=8)

- Runs 3 units, then waits, then runs 7 more units

P2: Arrived at T=3, finishes at T=10

- Waits only 1 unit

- Gets preempted at T=7, resumes at T=8

- Benefits from SRTF optimization

P3: Arrived at T=7, finishes at T=8

- Waits 0 units (runs immediately)

- Short job gets priority treatment

P4: Arrived at T=8, finishes at T=13

- Waits 2 units

- Also benefits from being shorter than P1

Comparison: FCFS vs SRTF for This Workload

FCFS Order: [P1, P2, P3, P4]

0-10: P1

10-16: P2

16-17: P3

17-20: P4

Average turnaround: (10 + 13 + 10 + 3) / 4 = 9 units

SRTF Order (with preemptions):

Average turnaround: 8.25 units ✅ BETTER

SRTF saves 0.75 units on average by running short jobs first.

Why P1 Waits So Long:

Total time: 20 units

P1's burst: 10 units

P1's waiting: 20 - 10 = 10 units

Breakdown of P1's time:

T=0-3: Running (3 units)

T=3-10: Waiting (7 units) - P2, P3, P4 running

T=10-13: Waiting (3 units) - P4 running

T=13-20: Running (7 units)

Context Switches in SRTF:

Switch 1: P1 → P2 at T=3

Switch 2: P2 → P3 at T=7

Switch 3: P3 → P2 at T=8 (P2 resumes)

Switch 4: P2 → P4 at T=10

Switch 5: P4 → P1 at T=13

Total: 5 context switches

Overhead cost: 5 × context_switch_cost

Real-World Implication:

- Optimal for throughput: Average turnaround = 8.25 units

- Unfair to long jobs: P1 waits 10 units

- Requires burst time prediction: Interactive systems can’t know burst times in advance

- High overhead: Multiple preemptions cost CPU cycles

This is why real systems use MLFQ with aging instead: provides most of SRTF’s benefits while avoiding starvation.

Problem 24: Non/Preemptive Priority Scheduling (lower value = higher priority)

Consider the following 5 processes in a system. Assume that lower values indicate higher priority.

| Process | Arrival Time | Burst Time | Priority |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 11 | 2 |

| P2 | 5 | 28 | 0 |

| P3 | 12 | 2 | 3 |

| P4 | 2 | 10 | 1 |

| P5 | 9 | 16 | 4 |

(a) Draw the Gantt chart if we employ non-preemptive priority scheduling. Compute the turnaround time for each process.

(b) Draw the Gantt chart if we employ preemptive priority scheduling. Compute the turnaround time for each process.

LLM Solution

Part (a): Non-Preemptive Priority Scheduling

Priority Order (lower = higher priority):

- P2 (priority 0) - highest

- P4 (priority 1)

- P1 (priority 2)

- P3 (priority 3)

- P5 (priority 4) - lowest

Gantt Chart:

| Time | 0-2 | 2-11 | 11-13 | 13-39 | 39-55 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | P1 | P1 | P4 | P2 | P5 |

Wait, let me retrace. At T=0, only P1 has arrived, so P1 must run. At T=2, P4 arrives (priority 1), but P1 is running and non-preemptive, so P1 continues. At T=5, P2 arrives (priority 0, highest), but P1 is still running. At T=9, P5 arrives. At T=11, P1 completes.

Actually, I need to reconsider. In non-preemptive priority, we run the highest priority process in the ready queue, not the one currently running. Let me retrace:

T=0: P1 arrives. Ready=[P1]. CPU: P1

T=0-2: P1 runs (2 units done, 9 remaining)

T=2: P4 arrives (priority 1). Ready=[P1(rem=9,pri=2), P4(burst=10,pri=1)]

P4 has higher priority (1 < 2) but P1 is running.

Non-preemptive: P1 continues

T=2-5: P1 runs (5 units done, 6 remaining)

T=5: P2 arrives (priority 0, highest). Ready=[P1(rem=6,pri=2), P4(burst=10,pri=1), P2(burst=28,pri=0)]

P2 has highest priority but P1 is running.

Non-preemptive: P1 continues

T=5-9: P1 runs (9 units done, 2 remaining)

T=9: P5 arrives (priority 4). Ready=[P1(rem=2,pri=2), P4(burst=10,pri=1), P2(burst=28,pri=0), P5(burst=16,pri=4)]

P1 still running, non-preemptive

T=9-11: P1 runs (11 units done, completes)

T=11: P1 completes. Ready=[P4(burst=10,pri=1), P2(burst=28,pri=0), P5(burst=16,pri=4)]

Highest priority: P2 (0 < 1 < 4)

CPU: P2

T=11-39: P2 runs (28 units done, completes)

T=39: P2 completes. Ready=[P4(burst=10,pri=1), P5(burst=16,pri=4)]

Highest priority: P4 (1 < 4)

CPU: P4

T=39-49: P4 runs (10 units done, completes)

T=49: P4 completes. Ready=[P5(burst=16,pri=4)]

CPU: P5

T=49-65: P5 runs (16 units done, completes)

Wait, P3 hasn’t appeared yet. P3 arrives at T=12, priority 3.

Let me retrace again more carefully:

T=0: P1 arrives (burst=11, pri=2). Ready=[P1]. CPU: P1

T=0-2: P1 runs (2 done, 9 remaining)

T=2: P4 arrives (burst=10, pri=1). Ready=[P1(rem=9,pri=2), P4(burst=10,pri=1)]

P1 running, non-preemptive: P1 continues

T=2-5: P1 runs (5 done, 6 remaining)

T=5: P2 arrives (burst=28, pri=0). Ready=[P1(rem=6,pri=2), P4(burst=10,pri=1), P2(burst=28,pri=0)]

P1 running, non-preemptive: P1 continues

T=5-9: P1 runs (9 done, 2 remaining)

T=9: P5 arrives (burst=16, pri=4). Ready=[P1(rem=2,pri=2), P4(burst=10,pri=1), P2(burst=28,pri=0), P5(burst=16,pri=4)]

P1 running, non-preemptive: P1 continues

T=9-11: P1 runs (11 done, completes)

At T=11, P1 completes

T=11: Ready=[P4(burst=10,pri=1), P2(burst=28,pri=0), P5(burst=16,pri=4)]

P3 hasn't arrived yet (arrives at T=12)

Highest priority: P2 (pri=0)

CPU: P2

T=11-12: P2 runs (1 done, 27 remaining)

T=12: P3 arrives (burst=2, pri=3). Ready=[P2(rem=27,pri=0), P4(burst=10,pri=1), P5(burst=16,pri=4), P3(burst=2,pri=3)]

P2 running, non-preemptive: P2 continues

T=12-39: P2 runs (27 done, completes)

T=39: Ready=[P4(burst=10,pri=1), P5(burst=16,pri=4), P3(burst=2,pri=3)]

Highest priority: P4 (pri=1 < 3 < 4)

CPU: P4

T=39-49: P4 runs (10 done, completes)

T=49: Ready=[P5(burst=16,pri=4), P3(burst=2,pri=3)]

Highest priority: P3 (pri=3 < 4)

CPU: P3

T=49-51: P3 runs (2 done, completes)

T=51: Ready=[P5(burst=16,pri=4)]

CPU: P5

T=51-67: P5 runs (16 done, completes)

Gantt Chart (Corrected):

| Time | 0-11 | 11-39 | 39-49 | 49-51 | 51-67 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | P1 | P2 | P4 | P3 | P5 |

Turnaround Times:

| Process | Arrival | Burst | Completion | Turnaround |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| P2 | 5 | 28 | 39 | 34 |

| P3 | 12 | 2 | 51 | 39 |

| P4 | 2 | 10 | 49 | 47 |

| P5 | 9 | 16 | 67 | 58 |

Part (b): Preemptive Priority Scheduling

In preemptive priority, when a higher priority process arrives, it immediately preempts the current process.

T=0: P1 arrives (burst=11, pri=2). Ready=[P1]. CPU: P1

T=0-2: P1 runs (2 done, 9 remaining)

T=2: P4 arrives (burst=10, pri=1). Remaining: P1(rem=9,pri=2), P4(burst=10,pri=1)

P4 higher priority (1 < 2). PREEMPT P1

CPU: P4

T=2-5: P4 runs (3 done, 7 remaining)

T=5: P2 arrives (burst=28, pri=0). Remaining: P1(rem=9,pri=2), P4(rem=7,pri=1), P2(burst=28,pri=0)

P2 highest priority (0 < 1 < 2). PREEMPT P4

CPU: P2

T=5-9: P2 runs (4 done, 24 remaining)

T=9: P5 arrives (burst=16, pri=4). Remaining: P1(rem=9,pri=2), P4(rem=7,pri=1), P2(rem=24,pri=0), P5(burst=16,pri=4)

P2 highest priority (0 < 1 < 2 < 4). No preemption

CPU: P2 continues

T=9-12: P2 runs (4 done, 20 remaining)

T=12: P3 arrives (burst=2, pri=3). Remaining: P1(rem=9,pri=2), P4(rem=7,pri=1), P2(rem=20,pri=0), P5(burst=16,pri=4), P3(burst=2,pri=3)

P2 highest priority. No preemption

CPU: P2 continues

T=12-37: P2 runs (20 done, completes)

T=37: Ready=[P1(rem=9,pri=2), P4(rem=7,pri=1), P5(burst=16,pri=4), P3(burst=2,pri=3)]

Highest priority: P4 (pri=1)

CPU: P4

T=37-44: P4 runs (7 done, completes)

T=44: Ready=[P1(rem=9,pri=2), P5(burst=16,pri=4), P3(burst=2,pri=3)]

Highest priority: P1 (pri=2 < 3 < 4)

CPU: P1

T=44-53: P1 runs (9 done, completes)

T=53: Ready=[P5(burst=16,pri=4), P3(burst=2,pri=3)]

Highest priority: P3 (pri=3 < 4)

CPU: P3

T=53-55: P3 runs (2 done, completes)

T=55: Ready=[P5(burst=16,pri=4)]

CPU: P5

T=55-71: P5 runs (16 done, completes)

Gantt Chart (Preemptive):

| Time | 0-2 | 2-5 | 5-37 | 37-44 | 44-53 | 53-55 | 55-71 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | P1 | P4 | P2 | P4 | P1 | P3 | P5 |

Wait, this doesn’t look right. P4 appears twice. Let me recalculate the completion time for P2.

From T=5 to T=37: that’s 32 units. But P2 has burst=28. So P2 should finish at T=5+28=33, not 37.

Let me retrace:

T=0-2: P1 runs 2 units (9 remaining)

T=2-5: P4 runs 3 units (7 remaining)

T=5-33: P2 runs 28 units (0 remaining, completes)

T=33: Ready=[P1(rem=9,pri=2), P4(rem=7,pri=1), P5(burst=16,pri=4), P3(burst=2,pri=3)]

Highest priority: P4 (pri=1)

CPU: P4

T=33-40: P4 runs 7 units (0 remaining, completes)

T=40: Ready=[P1(rem=9,pri=2), P5(burst=16,pri=4), P3(burst=2,pri=3)]

Highest priority: P1 (pri=2 < 3 < 4)

CPU: P1

T=40-49: P1 runs 9 units (0 remaining, completes)

T=49: Ready=[P5(burst=16,pri=4), P3(burst=2,pri=3)]

Highest priority: P3 (pri=3 < 4)

CPU: P3

T=49-51: P3 runs 2 units (0 remaining, completes)

T=51: Ready=[P5(burst=16,pri=4)]

CPU: P5

T=51-67: P5 runs 16 units (0 remaining, completes)

Gantt Chart (Corrected):

| Time | 0-2 | 2-5 | 5-33 | 33-40 | 40-49 | 49-51 | 51-67 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | P1 | P4 | P2 | P4 | P1 | P3 | P5 |

Turnaround Times (Preemptive):

| Process | Arrival | Burst | Completion | Turnaround |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 11 | 49 | 49 |

| P2 | 5 | 28 | 33 | 28 |

| P3 | 12 | 2 | 51 | 39 |

| P4 | 2 | 10 | 40 | 38 |

| P5 | 9 | 16 | 67 | 58 |

Problem 25: Non/Preemptive Priority Scheduling (higher value = higher priority)

Consider the following 5 processes in a system. Assume that higher values indicate higher priority.

| Process | Arrival Time | Burst Time | Priority |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| P2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| P3 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| P4 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| P5 | 4 | 2 | 5 |

(a) Draw the Gantt chart if we employ non-preemptive priority scheduling. Compute the turnaround time for each process.

(b) Draw the Gantt chart if we employ preemptive priority scheduling. Compute the turnaround time for each process.

Problem 26: Round Robin (quantum=2)

Consider the following 4 processes in a system.

| Process | Arrival Time | Burst Time |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 5 |

| P2 | 1 | 3 |

| P3 | 2 | 1 |

| P4 | 3 | 2 |

| P5 | 4 | 3 |

Draw a Gantt chart illustrating the execution of these processes using round robin scheduling with a quantum of 2. Compute the average waiting time and average turnaround time. Note: At any given time, a newly arriving process is put to the back of the ready queue before the executing process is preempted. That is, the preempted process is always the last process in the ready queue.

LLM Solution

Round Robin with Quantum = 2

This problem requires careful tracking of the ready queue. At each decision point, when a new process arrives, it goes to the back of the queue BEFORE the current process is preempted.

Execution Trace:

| Time | Event | Ready Queue | CPU | Remaining Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-1 | P1 arrives | [P1] | P1 (1 of 2) | P1:4 |

| 1 | P2 arrives | [P1, P2] | P1 (2 of 2) | P1:3, P2:3 |

| 1-2 | P1 completes quantum | [P2, P1] | P2 (1 of 2) | P1:3, P2:2 |

| 2 | P3 arrives | [P2, P1, P3] | P2 (2 of 2) | P1:3, P2:1, P3:1 |

| 2-3 | P2 completes quantum | [P1, P3, P2] | P1 (1 of 2) | P1:3, P2:1, P3:1 |

| 3 | P4 arrives | [P1, P3, P2, P4] | P1 (2 of 2) | P1:2, P2:1, P3:1, P4:2 |

| 3-4 | P1 completes quantum | [P3, P2, P4, P1] | P3 (1 of 2) | P1:2, P2:1, P3:1, P4:2 |

| 4 | P5 arrives, P3 completes | [P2, P4, P1, P5] | P2 (1 of 2) | P1:2, P2:1, P4:2, P5:3 |

| 4-5 | P2 completes quantum/finishes | [P4, P1, P5] | P4 (1 of 2) | P1:2, P4:2, P5:3 |

| 5-6 | P4 completes quantum | [P1, P5, P4] | P1 (1 of 2) | P1:2, P4:1, P5:3 |

| 6-7 | P1 completes quantum | [P5, P4, P1] | P5 (1 of 2) | P1:1, P4:1, P5:2 |

| 7-8 | P5 completes quantum | [P4, P1, P5] | P4 completes | P1:1, P5:2 |

| 8-9 | P4 done | [P1, P5] | P1 (1 of 2) | P1:1, P5:2 |

| 9-10 | P1 completes | [P5] | P5 (1 of 2) | P5:2 |

| 10-12 | P5 finishes | [] | (idle) | Done |

Gantt Chart:

| Time | 0-2 | 2-3 | 3-5 | 5-6 | 6-8 | 8-9 | 9-10 | 10-11 | 11-12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | P1 | P2 | P1 | P2 | P1 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P5 |

| Remaining | 3 → 1 | 2 → 1 | 1 → 0 | 3 → 2 | 2 → 1 | 1 → 0 | 2 → 1 | 3 → 1 | 1 → 0 |

Wait, let me recalculate more carefully with correct quantum accounting:

Corrected Detailed Trace:

- T=0: P1 arrives, ready=[P1]

- T=0-2: P1 runs 2 units (quantum expires), remaining=3, ready=[P1]

- T=1: P2 arrives, goes to back, ready=[P1, P2]

- T=2: P1 preempted, ready=[P2, P1]

- T=2-3: P2 runs 1 unit, then P3 arrives (total 1), remaining=2, ready=[P2, P1, P3]

- Actually P2 should run 2 units or until it finishes. Since burst=3, it has 3 units.

Let me restart with a clearer approach:

| Time | Ready Queue | Running | Run Time | Remaining | End Time | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | [P1] | P1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | P1 runs full quantum |

| 1 | [P1, P2] | P1 | (continuing) | P2: 3 | - | P2 arrives, queued |

| 2 | [P2, P1] | P2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | P1 preempted, P2 runs full quantum |

| 2 | [P2, P1, P3] | P2 | (continuing) | P3: 1 | - | P3 arrives, queued |

| 3 | [P1, P3, P2] | P1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | P2 preempted, P1 runs full quantum |

| 3 | [P1, P3, P2, P4] | P1 | (continuing) | P4: 2 | - | P4 arrives, queued |

| 4 | [P3, P2, P4, P1] | P3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | P1 preempted, P3 runs (burst=1 < quantum=2), COMPLETES |

| 4 | [P2, P4, P1, P5] | P2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | P2 arrives, P2 runs 1 unit, COMPLETES |

| 5 | [P4, P1, P5] | P4 | 2 | 0 | 7 | P4 runs full quantum, COMPLETES |

| 7 | [P1, P5] | P1 | 2 | 0 | 9 | P1 runs full quantum, COMPLETES |

| 9 | [P5] | P5 | 2 | 1 | 11 | P5 runs full quantum (remaining=3, so 2 units) |

| 11 | [P5] | P5 | 1 | 0 | 12 | P5 runs remaining 1 unit, COMPLETES |

Gantt Chart:

| Time | 0-2 | 2-4 | 4-5 | 5-7 | 7-9 | 9-11 | 11-12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P1 | P5 | P5 |

Calculations:

| Process | Arrival | Burst | Completion | Turnaround | Waiting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 4 |

| P2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| P3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| P4 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 2 |

| P5 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 8 | 5 |

Average Waiting Time: (4 + 1 + 1 + 2 + 5) / 5 = 2.6 units

Average Turnaround Time: (9 + 4 + 2 + 4 + 8) / 5 = 5.4 units

Problem 27: FCFS vs RR (quantum=2)

Consider the following 3 processes in a system.

| Process | Arrival Time | Burst Time |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 5 |

| P2 | 1 | 7 |

| P3 | 3 | 4 |

Draw a Gantt chart illustrating the execution of these processes using FCFS and round robin scheduling with a quantum of 2. Compute the average waiting time and average turnaround time.

Problem 28: Single-threaded vs multi-threaded Work

Consider the following function named Work, which performs I/O for 1 time unit and then performs computation for 1 time unit within a loop.

void Work(int noOfIterations){

for (int i = 0; i < noOfIterations; i++){

DoIO(); // I/O takes 1 time unit

Compute(); // Computation takes 1 time unit

}

}

int main1(int argc, char *argv[]){

Work(10); // Do the work in a single-threaded process

return 0;

}

int main2(int argc, char *argv[]){

CreateThread(Work(5)); // Create a thread to run Work with noOfIterations = 5

CreateThread(Work(5)); // Create a thread to run Work with noOfIterations = 5

wait_until_both_threads_are_done();

return 0;

}💡 Note: The calls CreateThread(Work(5)); as written will invoke Work(5) immediately and pass its return value to CreateThread. To create a thread that runs Work with noOfIterations = 5, pass the function and its argument correctly (for example, CreateThread(Work, 5) or the equivalent pthread_create invocation).

(a) Assume that the OS does not support threads. So the programmer designs its main function to be single-threaded and codes main1() shown above. Assuming this is the only process in the system and the machine has 1 CPU, how long does the program take to finish? Answer the same question when the machine has 2 CPUs.

| Time | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPU | ||||||||||||||||||||