02 - Process Management

Problem 1: Short Answer Questions

(a) What’s the difference between a program and a process?

LLM Solution

A program is a static, stored file containing executable code and data. A process is the dynamic execution of that program—a running instance with its own memory space, registers, state, and process ID.

Elaboration:

The distinction between these two concepts is fundamental to understanding operating systems:

Program:

- Static artifact: code and data stored on disk

- Passive: cannot perform computation by itself

- Example: a compiled binary file

/bin/ls - Can exist for years without being executed

- Multiple processes can be created from the same program

Process:

- Dynamic entity: created when a program is executed

- Active: consumes CPU time, memory, and I/O resources

- Has its own state: program counter, registers, memory layout

- Each process has a unique process ID (PID)

- Has a lifecycle: created (fork), running/blocked/ready, terminated

Relationship:

When you execute the same program twice, the OS creates two separate processes with different PIDs, different memory spaces, and independent execution state—even though they execute the same code.

Example: If you run /bin/ls five times in separate terminal windows, you have five distinct processes, all executing the same program code.

(b) List the 4 sections of the address space of a process. Briefly describe what’s stored in section.

LLM Solution

The process address space contains four main sections: text (code), initialized data (global/static variables), uninitialized data (BSS), and heap/stack (dynamic memory).

Elaboration:

The process address space is divided into distinct sections, each serving a specific purpose:

1. Text Segment (Code)

- Contains the executable machine instructions

- Read-only (prevents accidental code modification)

- Loaded from the program binary file

- Shared across multiple instances of the same program (to save memory)

2. Initialized Data Segment (Data)

- Global and static variables explicitly initialized with values

- Example:

int x = 10;at global scope - Read/write: values can be modified at runtime

- Size known at compile time

- Loaded from the program binary

3. Uninitialized Data Segment (BSS—Block Started by Symbol)

- Global and static variables not explicitly initialized

- Example:

int x;at global scope (implicitly initialized to 0) - Read/write

- Size known at compile time

- Not stored in the binary (saves disk space); kernel zeros this segment at load time

4. Heap & Stack

- Heap: dynamically allocated memory via

malloc(), grows upward - Stack: local variables, function parameters, return addresses; grows downward

- Both read/write

- Size not known at compile time; grows/shrinks at runtime

Memory Layout:

High Address (Kernel Space)

↓

[Stack] ← function calls, local variables

|↓

[Unused Space]

↑|

[Heap] ← malloc()

[BSS]

[Data]

[Text] ← code

Low Address (Program Start)

(c) Draw the process transition diagram. Mark each transition appropriately.

LLM Solution

A process transitions between five primary states: New (created), Ready (waiting for CPU), Running (executing on CPU), Blocked (waiting for I/O), and Terminated (finished).

Elaboration

The process transition diagram shows the lifecycle of a process and how the OS manages state changes:

The Five Process States:

-

New: Process is being created

- PCB allocated

- Initial values set

- Resources prepared (but not yet assigned)

-

Ready: Process is prepared and waiting for CPU time

- Has all resources except CPU

- Waiting in the ready queue

- Can be scheduled anytime

-

Running: Process is currently executing on the CPU

- Only one process per CPU core can be running

- Gets interrupted by timer or I/O request

- Can transition to ready or blocked

-

Blocked (or Waiting): Process is waiting for I/O or other event

- Cannot run even if CPU is available

- Waiting for disk read, network packet, keyboard input, etc.

- Moves back to ready when event completes

-

Terminated: Process has finished execution

- Code no longer running

- Resources being released (or already released)

- PCB may persist briefly to allow parent to collect exit status (zombie state)

State Transition Diagram:

Scheduler

┌──────────────┐

│ ▼

┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐

│ Ready │───▶│ Running │

└─────────┘ └─────────┘

▲ │ │

│ │ │ I/O Request

│ │ │

│ ┌───┘ │

│ │ ▼

│ │ ┌────────┐

│ I/O │ │ Blocked│

│ Complete │ └────────┘

│ │ │

└──────────┘ │

│

┌─────────────────┘

│ (or Timer Interrupt

│ or Voluntary)

│

▼

┌───────────────┐

│ Terminated │

└───────────────┘

Typical Transitions:

- New → Ready:

fork()creates process, OS adds to ready queue - Ready → Running: Scheduler selects process, dispatcher loads state onto CPU

- Running → Ready: Timer interrupt fires (time quantum expires), process moved back to ready queue

- Running → Blocked: Process calls blocking system call (read disk, wait on I/O)

- Blocked → Ready: I/O completes (interrupt), process moved back to ready queue

- Running → Terminated: Process calls

exit()or receives termination signal - Terminated: Process removed from ready queue (may persist as zombie briefly)

Key Points:

- Process can only be Running on one CPU at a time

- Multiple processes can be Ready (waiting for CPU)

- Multiple processes can be Blocked (waiting for different I/O events)

- The scheduler constantly transitions processes between ready and running

- Context switching is the mechanism that executes these transitions

(d) Why is it necessary for the OS to assign a unique process id to each process in the system?

LLM Solution

Unique process IDs (PIDs) allow the OS to identify and manage individual processes. Without PIDs, the OS would have no way to track processes, enforce security policies, route signals correctly, or maintain parent-child relationships.

Elaboration:

Process IDs serve as the fundamental identifier that makes process management possible:

Identification & Tracking:

- OS maintains data structures (like the process table) indexed by PID

- Kernel can quickly look up a process’s PCB using its PID

- Enables the OS to distinguish between different processes

Signal Delivery:

- Users/processes send signals to specific processes using PIDs

- Example:

kill -9 1234sends SIGKILL to process 1234 - Without unique IDs, OS couldn’t route signals correctly

Parent-Child Relationships:

- Parent process needs to wait for specific children:

waitpid(child_pid) - Allows orphan detection and handling

- Enables process family trees: e.g., all children of PID 1000

Security & Resource Control:

- OS must track which resources belong to which process

- File descriptors, memory, CPU time are tied to specific PIDs

- Enforces isolation: one process cannot steal another’s resources

- User/group permissions are checked per process

Process Control:

- Suspend/resume:

kill -STOP,kill -CONT - Terminate:

kill -TERM,kill -KILL - Monitor:

ps,topcommands list processes by PID

Example Use Case:

$ ps aux # Lists all processes with their PIDs

$ kill 1234 # Terminates process with PID 1234

$ waitpid(1234) # Parent waits for specific child process

$ strace -p 5678 # Trace system calls of process 5678Without unique PIDs, the OS would treat all processes identically and could not provide process-level isolation, control, or accountability.

(e) What is a Process Control Block (PCB)? What is it used for? List 1 item that must be stored in a PCB.

LLM Solution

A Process Control Block (PCB) is a kernel data structure that stores all information about a process. The OS uses it to manage, schedule, and control process execution. PCB contains: process state, PID, priority, registers, memory pointers, file descriptors, and more.

Elaboration:

The PCB is the kernel’s database entry for a single process—it is the most fundamental data structure in process management:

Definition:

A Process Control Block is a kernel data structure (typically in kernel memory) that maintains complete information about one process. The OS maintains one PCB per process in the system.

Primary Uses:

-

Scheduling: OS uses PCB to decide which process to run next

- Process state (ready, running, blocked)

- Priority

- Time quantum used

-

Context Switching: When switching processes, OS saves old process’s state in its PCB and restores new process’s state from its PCB

-

Resource Management: OS tracks resources assigned to each process

- Memory allocation

- Open file descriptors

- Signal handlers

-

Accounting: Track process statistics

- CPU time used

- Memory usage

- I/O operations

Essential PCB Contents:

| Item | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Process ID (PID) | Unique identifier |

| Process State | Running, Ready, Blocked, Stopped, Terminated |

| Program Counter (PC) | Address of next instruction to execute |

| Registers | CPU registers (EAX, EBX, etc.) |

| Memory Pointers | Base/limit of code, data, stack segments |

| Priority | Scheduling priority |

| Open File Table | File descriptors this process has open |

| Signal Mask | Which signals this process handles |

| Parent PID | PID of parent process |

| CPU Time Used | Total CPU time consumed so far |

Example (from Linux):

The Linux PCB is called the task_struct and contains ~200 fields!

(f) What’s meant by process dispatch? Briefly explain.

LLM Solution

Process dispatch is the act of the OS scheduler selecting a process from the ready queue and allocating the CPU to it for execution. The dispatcher loads the selected process’s state from its PCB and starts executing it.

Elaboration:

Process dispatch is the execution step that follows the scheduling decision:

Scheduling vs. Dispatch:

- Scheduler: Decides which process should run next (policy decision)

- Dispatcher: Actually makes that process run (mechanism)

What Happens During Dispatch:

-

Save Old Process State: Save current process’s registers and state to its PCB (if not the first dispatch)

-

Select New Process: Scheduler picks next process from ready queue based on scheduling algorithm

-

Load New Process State: Dispatcher loads the selected process’s PCB:

- Restore CPU registers from PCB

- Set program counter to where process left off

- Update memory management unit (MMU) for new process’s address space

- Update privilege level if needed

-

Resume Execution: CPU continues executing the selected process’s code

Dispatch Overhead:

Process dispatch itself has a cost—the dispatch latency is the time spent context switching. This is wasted CPU time that doesn’t advance any useful computation. Frequent context switching can significantly reduce system throughput.

Example:

Time 0: Process A running (dispatch latency ≈ 1µs)

Time 1: Process B running (dispatch latency ≈ 1µs)

Time 2: Process C running (dispatch latency ≈ 1µs)

In a real system, dispatch operations happen thousands of times per second, so minimizing dispatch latency is important.

(g) What is a context switch? Briefly describe what the OS does during a context switch? Is context switch a desirable thing if our goal is to increase the throughput of the system?

LLM Solution

A context switch is when the OS stops one process and starts another. The OS saves the running process’s state (registers, PC, memory map) to its PCB, loads another process’s state from its PCB, and resumes execution. Context switches are necessary for multitasking but reduce throughput due to dispatch overhead.

Elaboration:

Context switching is fundamental to multitasking but involves important trade-offs:

Definition:

A context switch is the mechanism by which the OS transitions from executing one process to executing another. The “context” is the complete CPU state needed to resume a process:

- All CPU registers (EAX, EBX, EIP, etc.)

- Program counter

- Stack pointer

- Memory management state (page tables)

- Privilege level

What OS Does During Context Switch:

-

Interrupt/Trap Handling: An interrupt or trap signal triggers the context switch (timer interrupt, system call, I/O completion)

-

Save Current State: Kernel saves the running process’s entire CPU state to its PCB

current_process->registers = CPU.registers current_process->program_counter = CPU.eip current_process->state = READY // or BLOCKED -

Select Next Process: Scheduler chooses which ready process to run next

-

Load New State: Dispatcher restores the new process’s state from its PCB

CPU.registers = new_process->registers CPU.eip = new_process->program_counter MMU.page_table = new_process->page_table -

Resume Execution: CPU continues with new process

Cost of Context Switching:

Direct Costs:

- Saving/restoring registers: ~10-100 CPU cycles

- TLB (translation lookaside buffer) flush: expensive

- Cache invalidation: lost cache locality

Indirect Costs:

- Cache misses when new process starts

- Memory bus traffic

Impact on Throughput:

Bad for Throughput:

- Frequent context switches waste CPU cycles on overhead

- Each switch costs time that doesn’t advance any useful computation

- Too many switches:

Necessary for Responsiveness:

- But context switches are essential for:

- User responsiveness (interactive systems)

- I/O device utilization (multitasking)

- Fairness (multiple users)

Trade-off:

Few context switches → High throughput, poor responsiveness

Many context switches → Low throughput, good responsiveness

The OS must find the right balance using scheduling algorithms.

(h) What’s the name of the “first” process in Linux. What’s its process id? Who creates it?

LLM Solution

The first user-space process in Linux is init (traditionally called init, now systemd on modern systems). It always has PID 1. The kernel creates it directly after boot; there is no parent process.

Elaboration:

Understanding init is fundamental to understanding Linux process hierarchy:

Process Name & PID:

| Aspect | Value |

|---|---|

| Traditional Name | init |

| Modern Name | systemd (on systemd systems) |

| PID | Always 1 |

| Parent PID | None (kernel-created, no parent) |

Who Creates init:

The kernel itself creates init directly during boot:

- Kernel loads from bootloader

- Kernel initializes hardware and data structures

- Kernel creates the init process (PID 1) in kernel space

- Kernel transfers control to init’s

main()function

Role of init (PID 1):

-

Process Tree Root: Every other user process is a descendant of init

PID 1 (init/systemd) ├── PID 100 (bash) ├── PID 200 (sshd) └── PID 300 (apache) -

Starts System Services: init reads configuration files and spawns system services

- Networking daemons

- Web servers

- Logging services

- User shells

-

Handles Orphaned Processes: When a parent dies, init becomes the parent of orphaned children (“reparenting”)

- Allows init to reap zombie processes

- Prevents zombie process accumulation

-

System Shutdown: Coordinates graceful shutdown by terminating child processes

Key Properties:

- Immortal: Cannot be killed; if init terminates, system is in undefined state

- Root of Process Hierarchy: Parent of all processes (directly or indirectly)

- Handles SIGCHLD: Collects exit status of child processes

- Cannot Be Replaced: OS relies on init as the stable root

Verification:

$ ps aux | head

USER PID PPID COMMAND

root 1 0 /lib/systemd/systemd

root 2 0 [kthreadd]Note: PPID (parent PID) of init is 0 (kernel).

(i) What does the OS run if the ready queue is empty? Briefly explain.

LLM Solution

If the ready queue is empty (no processes ready to run), the OS runs the idle task (also called idle process or idle thread). The idle task is a special process that consumes CPU cycles when there is no useful work to do.

Elaboration:

The ready queue being empty is unusual but possible, and the OS must have a response:

What Triggers Empty Ready Queue:

- All processes are blocked waiting for I/O (disk reads, network, keyboard)

- All processes are sleeping (in timed wait states)

- System has completed all work and is waiting for new user input

The Idle Task:

Every operating system maintains a special idle task or idle process that runs when nothing else is ready:

Characteristics:

- Always present and ready to run

- Lowest priority (runs only when no other process is ready)

- Infinite loop that does minimal work

- Cannot be killed or scheduled out

What the Idle Task Does:

Typical Idle Task Code:

while (1) {

// Minimal work to keep CPU busy

// Typical implementations:

// 1. Halt instruction: pause CPU until interrupt

// 2. Busy wait: increment counter

// 3. Power management: reduce CPU frequency

}Actual Implementations:

-

Halt (HLT instruction)

- CPU pauses, consuming minimal power

- Awakens on next interrupt

- Most common on modern systems

-

Busy Wait

- Infinite loop checking for work

- Wastes CPU cycles

- No longer common (power inefficient)

-

Power Management

- Reduces CPU voltage/frequency

- Further reduces power consumption

Why Necessary:

-

Scheduler Simplification: Scheduler can assume a process always exists

while (1) { process = find_next_ready_process(); // Always finds idle if queue empty run(process); } -

Prevents Undefined Behavior: Without idle task, empty ready queue would crash scheduler

-

CPU Utilization Statistics: Kernel uses idle task time to measure how busy the system is

CPU Usage = 100% - Idle Task Time

Example (Linux):

Linux has idle_task (actually multiple per CPU core). When you see 95% idle in top output, the CPU is running the idle task.

(j) What’s the purpose of the “system idle task” and briefly explain how what this task does?

LLM Solution

The system idle task’s purpose is to provide a process for the scheduler to run when no user processes are ready. It ensures the scheduler always has something to dispatch, preventing crashes and allowing CPU utilization monitoring.

Elaboration:

The idle task serves multiple critical functions beyond merely “doing nothing”:

Primary Purposes:

-

Scheduler Stability

- Guarantees the scheduler always finds a runnable process

- Prevents scheduler from handling “no process” edge case

- Simplifies scheduling logic

-

CPU Power Management

- Allows CPU to enter low-power states when idle

- Reduces heat generation and energy consumption

- Critical for battery-powered devices

-

System Monitoring

- Tracks idle time to measure system load

- Users can see: “CPU 85% busy, 15% idle”

- Helps diagnose performance bottlenecks

What the Idle Task Actually Does:

Strategy 1: Halt Instruction (Most Efficient)

idle_task:

hlt ; Pause CPU, wait for interrupt

jmp idle_task- CPU stops executing instructions

- Wakes up on timer interrupt or I/O completion

- Minimal power consumption

- Most common on modern systems

Strategy 2: Yield/Wait (Polling)

while (1) {

// Voluntarily give up time slice

sched_yield();

// Or just spin (wasteful)

for (volatile int i = 0; i < 1000; i++);

}Strategy 3: Power States

while (1) {

// Negotiate lower CPU frequency

if (can_enter_low_power_state()) {

enter_c_state(); // C1, C2, C3 states

}

// Periodic wake-up to check for work

}Example (from top output):

%Cpu(s): 5.2 us, 2.1 sy, 0.0 ni, 92.7 id, 0.0 wa

^^^ 92.7% idle time = idle task running

Key Difference from Regular Processes:

| Aspect | Regular Process | Idle Task |

|---|---|---|

| Priority | Variable | Lowest (0) |

| Preemption | Yes (can be interrupted) | Only when other process ready |

| Behavior | Meaningful work | Minimal/no work |

| Memory Footprint | Variable | Minimal |

| Killable | Yes | No (system would crash) |

Without the idle task, the CPU would need special handling when all processes block, making the kernel significantly more complex.

(k) For each of the following system calls, give a condition that causes it to fail: fork, exec, chdir, read

LLM Solution

fork: Fails when insufficient memory for new process PCB and memory space. exec: Fails when the executable file doesn’t exist or is not in executable format. chdir: Fails when the directory doesn’t exist or process lacks permissions. read: Fails when the file descriptor is invalid or closed.

Elaboration:

Each system call can fail for different reasons related to resource constraints, permissions, or invalid arguments:

1. fork() Failure Conditions

The fork() call creates a new process by duplicating the current one. Main failure causes:

-

Insufficient Memory: Cannot allocate PCB for new process

pid_t pid = fork(); if (pid == -1) { perror("fork failed: out of memory"); }- Return value:

(stored in pid)

- Return value:

-

Process Limit Exceeded: User has too many processes (RLIMIT_NPROC)

-

Kernel Resource Exhaustion: Running out of PIDs, kernel memory

2. exec() Failure Conditions

The exec() family (execl, execv, execve) replaces the current process with a new program. Failure causes:

-

File Not Found: Executable file path doesn’t exist

execl("/bin/nonexistent", "nonexistent", NULL); // Returns -1, doesn't replace process -

Not Executable: File exists but isn’t an executable (permissions or format)

execl("/etc/passwd", "passwd", NULL); // Text file, not executable // EACCES or ENOEXEC error -

Bad Format: File isn’t a valid binary (wrong ELF magic number)

-

Permission Denied: File lacks execute permission for process

-

Not Enough Memory: Cannot allocate space for new program text/data

3. chdir() Failure Conditions

The chdir() call changes the process’s current working directory. Failure causes:

-

Directory Doesn’t Exist

chdir("/nonexistent/path"); // Returns -1- errno set to ENOENT (No such file or directory)

-

Not a Directory: Path points to a file, not directory

chdir("/etc/passwd"); // File, not directory // ENOTDIR error -

Permission Denied: Process lacks search (execute) permission on directory

chdir("/root"); // Regular user lacks permission // EACCES error -

Path Too Long: Directory path exceeds PATH_MAX

4. read() Failure Conditions

The read() call reads data from a file descriptor. Failure causes:

-

Invalid File Descriptor: FD doesn’t exist or was closed

read(999, buffer, 100); // FD 999 never opened // EBADF error -

File Closed: Descriptor was valid but was closed elsewhere

close(fd); read(fd, buffer, 100); // FD now invalid // EBADF error -

Bad Mode: FD opened write-only (not readable)

int fd = open("file", O_WRONLY); read(fd, buffer, 100); // Can't read from write-only FD // EBADF or EINVAL error -

I/O Error: Hardware error reading disk

// Disk read fails // EIO (Input/output error) -

Interrupted: Signal received during read

// EINTR error, read() may be retried

Summary Table:

| System Call | Failure Condition | Return Value |

|---|---|---|

| fork() | Out of memory | -1 |

| exec() | File not found | -1, errno=ENOENT |

| chdir() | Directory doesn’t exist | -1, errno=ENOENT |

| read() | Invalid file descriptor | -1, errno=EBADF |

(l) What is the difference between fork and exec system calls in Linux?

LLM Solution

fork: Creates a new child process as a duplicate of the parent; both parent and child execute the same program code from the fork() call onward. exec: Replaces the current process’s memory (code, data) with a new program; does not create a new process.

Elaboration:

Understanding fork and exec is critical to process creation in Unix:

fork() System Call

What It Does:

- Creates a new process (new PID)

- Duplicates the entire parent process:

- Copy of memory (code, data, heap, stack)

- Copy of file descriptors

- Copy of register state

- Both parent and child continue executing after fork()

- Returns twice: once in parent (returns child PID), once in child (returns 0)

Memory After fork():

Parent Process Child Process

[Text] ←→ [Text] (initially shared)

[Data] ←→ [Data] (copy-on-write)

[Heap] separate

[Stack] separate

[Variables] separate

Code Example:

int x = 5;

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

// Child process (pid == 0)

x = 10;

printf("Child: x = %d\n", x); // Prints 10

} else {

// Parent process (pid > 0)

printf("Parent: x = %d\n", x); // Prints 5

}Output:

Child: x = 10

Parent: x = 5 (separate memory spaces)

exec() System Call

What It Does:

- Does NOT create a new process

- Replaces current process’s program image:

- Discards old code, data, heap, stack

- Loads new executable into memory

- Keeps same PID, same file descriptors

- Overwrites the call site; doesn’t return (unless error)

- Only error code returns from exec()

Memory After exec():

Before exec() After exec()

[Old Code] → [New Code]

[Old Data] → [New Data]

[Old Heap] → [New Heap]

[Old Stack] → [New Stack]

Same PID, Same FDs

Code Example:

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

// Child: still in parent's process space

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", NULL);

printf("Never prints"); // exec() replaced this code!

// Process now running /bin/ls, not the original program

} else {

// Parent continues

wait(NULL);

}Key Differences:

| Feature | fork() | exec() |

|---|---|---|

| Creates Process? | Yes (new PID) | No (same PID) |

| Memory | Duplicate copy | Replaced |

| Return Value | Returns to caller | Never returns (on success) |

| File Descriptors | Inherited (copied) | Inherited (same) |

| Parent Affected? | No | N/A (usually done in child) |

| Use Case | Create new process | Launch different program |

Typical Usage Pattern (Shell Implementation):

To run a command like ls -la, shells use fork() + exec():

int main() {

// "ls -la" entered by user

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

// Child process

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", "-la", NULL);

perror("exec failed");

exit(1);

} else {

// Parent (shell) waits for child

wait(NULL);

// Shell prompt returns

printf("$ ");

}

}Why Both Needed:

- fork() alone: Can’t run different programs (stays in original code)

- exec() alone: Can’t create multiple processes (replaces caller)

- Together: Create new process running new program

(m) What’s the purpose of waitpid system call?

LLM Solution

waitpid() allows a parent process to wait for a specific child process to terminate and retrieve its exit status. It synchronizes parent-child execution and prevents zombie processes.

Elaboration:

The waitpid() system call is essential for parent-child synchronization and process cleanup:

Primary Purposes:

- Synchronization: Parent waits for child to complete before continuing

- Exit Status Retrieval: Obtain child’s exit code

- Zombie Prevention: Reap (clean up) terminated child process

- Process Management: Monitor multiple children selectively

Function Signature:

#include <sys/wait.h>

pid_t waitpid(pid_t pid, int *status, int options);Parameters:

-

pid: Which process to wait for

pid > 0: Wait for specific child (child’s PID)pid == -1: Wait for any childpid == 0: Wait for any child in same process grouppid < -1: Wait for any child in process group|pid|

-

status: Pointer to store exit status information

NULL: Discard status (don’t care about exit code)- Pointer: Receives detailed status (use WIFEXITED, WEXITSTATUS macros)

-

options: Flags (WNOHANG for non-blocking, etc.)

Return Value:

- On success: PID of child that terminated

- WNOHANG + no children ready: Returns 0 (non-blocking)

- Error: Returns -1

Example 1: Basic Usage

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

// Child: run some work

sleep(2);

exit(42);

} else {

// Parent: wait for child

int status;

waitpid(pid, &status, 0); // Blocks until child terminates

if (WIFEXITED(status)) {

int exit_code = WEXITSTATUS(status);

printf("Child exited with code %d\n", exit_code); // Prints 42

}

}Example 2: Waiting for Any Child

// Create 3 children

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

if (fork() == 0) {

sleep(i);

exit(i);

}

}

// Wait for all children (in any order)

int status;

pid_t child_pid;

while ((child_pid = waitpid(-1, &status, 0)) > 0) {

printf("Child %d terminated\n", child_pid);

}Example 3: Non-Blocking Wait (WNOHANG)

int status;

pid_t result = waitpid(child_pid, &status, WNOHANG);

if (result == 0) {

printf("Child still running\n");

} else if (result == child_pid) {

printf("Child has terminated\n");

} else if (result == -1) {

perror("waitpid");

}Why It’s Critical: Zombie Prevention

When a child terminates without waitpid():

Parent Child

| |

| fork() |

| | exit(0) <- becomes zombie

| | (waiting for parent to reap)

| |

| ... does other work ... (not waiting for child)

| |

| exit() <- child never reaped, zombie persists

The zombie remains in process table until parent calls waitpid():

$ ps aux

root 100 … <defunct> <- This is a zombieStatus Macros (to interpret returned status):

int status;

waitpid(pid, &status, 0);

if (WIFEXITED(status)) {

// Normal termination via exit()

int code = WEXITSTATUS(status); // 0-255

} else if (WIFSIGNALED(status)) {

// Terminated by signal

int sig = WTERMSIG(status); // Signal number

} else if (WIFSTOPPED(status)) {

// Stopped (suspended)

int sig = WSTOPSIG(status);

}Typical Shell Pattern:

// Parent (shell) creates child and waits

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", NULL); // Child runs ls

} else {

waitpid(pid, NULL, 0); // Shell waits for ls to finish

prompt(); // Then shows shell prompt again

}(n) What’s a “zombie” process? What information does the kernel store for a zombie process? When does the kernel completely clean up any information related to a zombie process?

LLM Solution

A zombie process is a child process that has terminated but whose parent hasn’t yet called waitpid() to retrieve its exit status. The kernel keeps the PCB and exit status until the parent reaps it. Cleanup occurs when the parent calls waitpid() or when the parent terminates.

Elaboration:

Zombie processes are a common source of confusion but represent a necessary part of Unix process management:

What is a Zombie?

A zombie is a process that has:

- Terminated: Called exit() or was killed

- Has Parent: Parent is still running

- Not Reaped: Parent hasn’t called waitpid()

The process is “dead” (no longer running) but the OS hasn’t completely removed it from the system.

Visual Timeline:

Parent Child

| |

| fork() |

|----creation----- |

| | exit(5)

| | Becomes ZOMBIE

| | Still in process table

| | Waiting for parent

| |

| ... doing other work ... | (zombie state)

| |

| waitpid(child) |

| Retrieves exit status |

| Child completely removed |

What Kernel Stores for Zombie:

Even though the zombie isn’t running, the kernel maintains a minimal PCB containing:

- Process ID (PID): Unique identifier

- Exit Status: The value passed to exit() (0-255) or termination signal

- Exit Code: Encoded in the status word

- Resource Usage Statistics:

- CPU time consumed

- Memory used

- I/O operations performed

- Parent PID: Who created this process

Zombie PCB Structure (simplified):

struct zombie_pcb {

int pid; // Process ID

int exit_status; // How/why it died

int parent_pid; // Parent's PID

struct rusage resource_usage; // CPU, memory stats

// No memory pages (already freed)

// No file descriptors (already closed)

// No registers (no longer needed)

}Notable Omissions:

- ❌ Memory space (code, data, heap, stack freed)

- ❌ File descriptors (closed)

- ❌ CPU registers

- ❌ Page tables

Only the small PCB remains in kernel memory.

Observable Zombie (on System):

$ ps aux | grep defunct

root 1234 5678 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? Z+ 14:32 0:00 [process] <defunct>

^^^ State = Z (zombie)

0 0 <- No memory/CPU usageWhen is Zombie Cleaned Up?

1. Parent Calls waitpid():

int status;

waitpid(child_pid, &status, 0);

// Zombie completely removed

// Parent gets exit status- This is the normal case

- Parent retrieves status and zombie is deleted

2. Parent Terminates (without waitpid):

// Parent exits while child is zombie

// OS reparents zombie to init (PID 1)

// init automatically calls waitpid()

// Zombie cleaned up- Fallback mechanism to prevent permanent zombies

- init is the janitor of the process tree

3. init Reaps the Process:

$ ps aux | grep defunct

# If you see a zombie with ppid=1, init will clean it up soonZombie Accumulation Problem:

If parent:

- Creates child

- Does not call waitpid()

- Never terminates

Result: Zombie persists indefinitely

// BAD CODE - creates zombie leak

int main() {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

if (fork() == 0) {

exit(0); // Child exits immediately

}

// Parent never calls waitpid()!

}

sleep(365*24*3600); // Parent runs for a year

// 1000 zombies remain in process table!

}Proper Pattern:

// GOOD CODE - prevents zombies

int main() {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

exit(0);

} else {

waitpid(pid, NULL, 0); // Immediately reap child

}

}

}Summary Table:

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| State | Terminated, not reaped |

| Memory | Freed (except small PCB) |

| CPU Usage | None |

| Storage | Minimal (~100-200 bytes in kernel) |

| Visible as | <defunct> in ps output |

| Cleanup Trigger | Parent calls waitpid() |

| If Parent Dies | init reparents and reaps |

| Persistence | Until parent reaps or parent dies |

Zombies are a necessary part of the Unix process model and represent the kernel’s way of giving the parent a chance to collect process statistics.

(o) When the parent process of a child process exits (terminates) in Linux, what happens to the child process? Briefly explain.

LLM Solution

When a parent terminates, the kernel automatically reparents all its orphaned children to init (PID 1). This ensures children have a valid parent and prevents zombie accumulation, as init automatically reaps all child processes.

Elaboration:

Orphan handling is a critical part of Linux process management:

What is an Orphaned Process?

A child process becomes orphaned when its parent terminates. Without automatic reparenting, the child would have no parent (no PPID), creating system inconsistency.

Before Reparenting (Briefly):

Parent (PID 100)

├─ Child A (PID 101)

├─ Child B (PID 102)

└─ Child C (PID 103)

Parent terminates...

Children are now ORPHANED!

After Reparenting (Automatic):

init (PID 1)

├─ Child A (PID 101) <- reparented

├─ Child B (PID 102) <- reparented

└─ Child C (PID 103) <- reparented

The Kernel’s Reparenting Process:

When parent terminates:

- Kernel detects parent exit

- Iterates through all processes

- Finds processes with ppid = dead_parent_pid

- Changes their ppid to 1 (init)

- Sends SIGHUP signal to orphaned children (usually ignored)

Code Example:

// Demonstrating orphan handling

int main() {

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

// Child process

printf("Child PID: %d, Parent PID: %d\n", getpid(), getppid());

sleep(5); // Sleep for 5 seconds

printf("Child PID: %d, Parent PID: %d\n", getpid(), getppid());

} else {

// Parent exits immediately

exit(0); // Parent terminates

}

}Output:

Child PID: 102, Parent PID: 100 <- Originally, parent is PID 100

Child PID: 102, Parent PID: 1 <- After parent exits, ppid changed to 1 (init)

Why Reparenting to init?

init is the ideal parent for orphans because:

- Always Running: init (PID 1) never terminates (system shutdown)

- Zombie Reaper: init is designed to automatically call waitpid() on all children

- Resource Management: Ensures orphans don’t accumulate as zombies

- Process Tree Stability: Maintains valid parent for every process

init’s Zombie Reaping Pattern:

// Simplified init process

void init_main() {

signal(SIGCHLD, handle_sigchld); // Install signal handler

while (1) {

// Periodically reap dead children

// When any child dies, SIGCHLD signal fires

pause(); // Wait for signal

}

}

void handle_sigchld(int sig) {

// Reap any dead children

while (waitpid(-1, NULL, WNOHANG) > 0);

}Comparison: Parent Alive vs Dead

| Scenario | Parent Alive | Parent Dead |

|---|---|---|

| Child’s Parent PID | Original parent PID | 1 (init) |

| Child Termination | Parent must call waitpid() | init calls waitpid() |

| Zombie Risk | High if parent doesn’t wait | None (init always reaps) |

| Child Signals | Sent to original parent | Sent to init |

Demonstrating Zombie Prevention via Reparenting:

Without Reparenting (Hypothetical):

// BAD: Create orphan without reparenting (can't do this in Unix)

int main() {

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

sleep(100);

} else {

exit(0); // Parent exits without waiting

// Child becomes zombie (would stay zombie forever)

}

}With Reparenting (Actual Unix Behavior):

// GOOD: Unix reparents orphan to init

int main() {

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

// Initially child of main process

getppid(); // Initially returns main's PID

sleep(100);

getppid(); // After main exits, returns 1 (init)

} else {

exit(0); // Parent exits

// Kernel automatically reparents child to init

// init automatically reaps when child terminates

}

}Practical Demonstration (on Linux):

$ bash

$ sleep 1000 & # Background process

[1] 1234 # PID 1234

$ exit # Bash exits

# In another terminal:

$ ps aux | grep sleep

# sleep now has ppid=1 (init), not ppid of bashSignal Handling After Reparenting:

Orphaned processes can still be targeted by signals:

kill 102still works (sends signal to process 102)- But signal disposition changes because init is parent

- init may handle SIGHUP differently than original parent

Summary:

Linux prevents orphan processes from becoming permanently zombied by automatically reparenting them to init, which ensures all dead children are properly reaped and resources are reclaimed.

(p) Briefly explain the difference between process creation in Linux and Windows.

LLM Solution

Linux uses fork() + exec() as two separate steps: fork() duplicates the parent process, exec() replaces the copy with a new program. Windows uses CreateProcess() as one atomic call that creates a process and loads a new program in a single step.

Elaboration:

The process creation philosophies of Linux and Windows reflect different design approaches:

Linux Process Creation (fork + exec)

Two-Step Model:

// Step 1: fork() - create duplicate

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

// Step 2: exec() - load new program

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", "-la", NULL);

// Now running different program, same PID

} else {

// Parent continues in original program

wait(NULL);

}Characteristics:

- Separation of Concerns: Process creation (fork) separate from program loading (exec)

- Duplication: Child is complete copy of parent (memory, file descriptors, signal handlers)

- Process ID: Child inherits parent’s PID initially, then exec() loads new program

- Flexibility: Can modify child before exec() (change environment, redirect I/O)

- Efficiency: Copy-on-write optimization reduces actual memory duplication

Advantages:

- Simple, elegant model

- Can manipulate child state before exec()

- File descriptor inheritance natural (just copied)

- Multiple children from same parent share code

Windows Process Creation (CreateProcess)

One-Step Model:

// Single call: create process AND load program

CREATE_PROCESS_INFO cpi = {0};

cpi.cb = sizeof(cpi);

CreateProcess(

"C:\\\\bin\\\\notepad.exe", // Program to execute

NULL, // Command line

NULL, NULL, // Security

FALSE, // Inherit handles

0, // Creation flags

NULL, // Environment

NULL, // Current directory

&cpi, &pi // Process/thread info

);

// New process created and already running new programCharacteristics:

- Atomic Operation: Process creation and program loading happen together

- No Duplication: Parent process not copied; new address space created from scratch

- Process ID: New process gets unique PID immediately

- Explicit Configuration: Parameters specify what program to run, what handles to inherit

- Immediate Execution: Process created in runnable state with new program

Advantages:

- Cleaner semantics: create process running program X

- No wasteful memory duplication

- Explicit control over handle inheritance

- No intermediate state (fork without exec)

Comparison Table:

| Aspect | Linux (fork + exec) | Windows (CreateProcess) |

|---|---|---|

| Model | Two separate steps | Single atomic call |

| Process Creation | fork() | CreateProcess() |

| Program Loading | exec() | CreateProcess() |

| Memory | Copy parent (COW) | Create fresh address space |

| Efficiency | Copy-on-write reduces overhead | No unnecessary copying |

| PID Continuity | Child has different PID than fork | New process has new PID |

| Parent State | Child inherits all parent state | Only specified items inherited |

| File Descriptors | Automatically inherited | Explicitly specified (inherit flag) |

| Signal Handlers | Inherited | N/A (Windows uses different model) |

| Flexibility | Can modify child before exec | No intermediate state to modify |

Why the Difference?

Unix Philosophy (Linux):

- Separation of concerns: each tool does one thing well

- fork() creates process, exec() loads program

- Flexible: can do setup between fork and exec

Windows Philosophy:

- All-or-nothing approach: create process ready to run

- Atomic operation prevents invalid states

- Explicit parameters for each aspect

Code Flow Comparison:

Linux - Sequential Steps:

Parent

|

| fork()

|-----> Child (duplicate of parent)

| |

| | exec("/bin/ls")

| |

| v

| Child (now running /bin/ls)

|

| wait()

|

v

Parent continues

Windows - Atomic Operation:

Parent

|

| CreateProcess("notepad.exe")

|

|-----> New Process (running notepad, brand new address space)

|

| WaitForSingleObject()

|

v

Parent continues

Practical Implications:

Linux: Redirect I/O before exec

int fd = open("output.txt", O_WRONLY | O_CREAT);

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

dup2(fd, STDOUT_FILENO); // Child: redirect stdout

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", NULL); // Now stdout goes to file

}Windows: Specify in CreateProcess

CREATE_PROCESS_INFO cpi = {0};

// Set up handle inheritance beforehand

CreateProcess("notepad.exe", ..., cpi, ...);Problem 2: Process Creation and Tree Analysis

How many processes are created when the following piece of code is executed in Linux? Draw the process tree for the processes thus created and show what’s printed by each process on the screen.

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int i = 0;

while (i < 4) {

if (fork() == 0)

i += 2;

else

i++;

}

printf("i = %d\n", i);

return 0;

}Required headers:

#include <unistd.h> // declares fork()

#include <stdio.h> // declares printf()

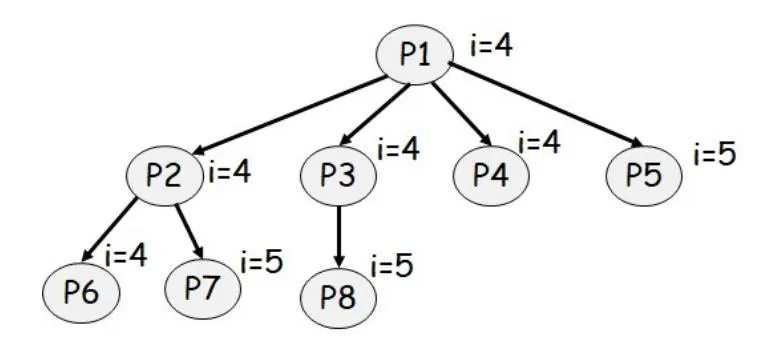

#include <stdlib.h> // declares exit()Instructor Solution

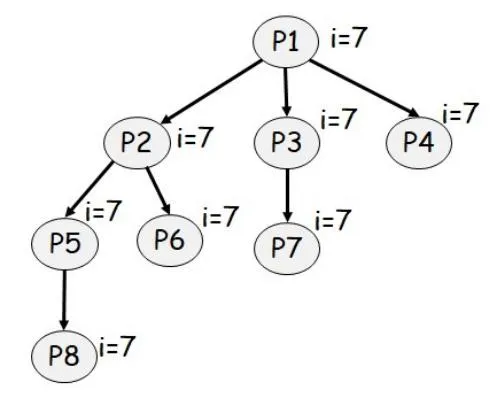

Problem 3: Fork Loop Process Counting

How many processes are created when the following piece of code is executed in Linux? Draw the process tree for the processes thus created and show what’s printed by each process on the screen.

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int i = 0;

while (i <= 6) {

fork();

if (i % 2 == 1)

i++;

else

i += 3;

}

printf("i = %d\n", i);

return 0;

}Required headers:

#include <unistd.h> // declares fork()

#include <stdio.h> // declares printf()

#include <stdlib.h> // declares exit()Instructor Solution

Elaboration (by LLM):

Total processes created: 8 (P1 through P8)

Process tree:

P1 (i=7)

/ | \

/ | \

P2 (i=7) P3 (i=7) P4 (i=7)

/ \ |

/ \ |

P5 (i=7) P6 (i=7) P7 (i=7)

|

|

P8 (i=7)

How the code works:

The key is understanding that fork() duplicates the entire process, including its variable values. Each process continues from the fork() call and executes the rest of the loop independently.

Loop iterations and fork points:

| Iteration | Value of i | fork() called? | i % 2 == 1? | i incremented by | Processes at end of iteration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 0 | YES | NO | +3 (becomes 3) | 2 (P1 and P2) |

| 2nd | 3 (P1), 3 (P2) | YES (both) | YES | +1 (becomes 4) | 4 (P1, P2, P3, P4) |

| 3rd | 4 (all 4) | YES (all 4) | NO | +3 (becomes 7) | 8 (P1–P8) |

| 4th | 7 (all 8) | NO (loop exits) | - | - | 8 (all remain at i=7) |

Step-by-step execution trace:

Iteration 1 (i = 0):

- Process P1 is at the start with

i = 0 fork()is called → creates P2- Both P1 and P2 continue

i % 2 == 1is FALSE (0 is even)i += 3→ i becomes 3 in both processes- Processes: P1 (i=3), P2 (i=3)

Iteration 2 (i = 3):

- P1 calls

fork()→ creates P3 - P2 calls

fork()→ creates P4 i % 2 == 1is TRUE (3 is odd)i += 1→ i becomes 4 in all processes- Processes: P1 (i=4), P2 (i=4), P3 (i=4), P4 (i=4)

Iteration 3 (i = 4):

- All 4 processes call

fork()→ creates P5, P6, P7, P8 i % 2 == 1is FALSE (4 is even)i += 3→ i becomes 7 in all 8 processes- Processes: P1–P8 all have (i=7)

Iteration 4 (i = 7):

- Loop condition

i <= 6is FALSE - Loop exits (no more

fork()calls) - All 8 processes continue to

printf()

Output printed (each process prints once):

Each of the 8 processes will print:

i = 7

i = 7

i = 7

i = 7

i = 7

i = 7

i = 7

i = 7

The exact order may vary due to process scheduling, but the value printed is always i = 7.

Key insight:

Each fork() call doubles the number of processes (if both parent and child execute the fork in the same iteration). This exponential growth is why we get:

- After iteration 1: 2 processes

- After iteration 2: 4 processes

- After iteration 3: 8 processes

Problem 4: Process Output Analysis

What would be the output of the following code segments when run in Linux?

int g = 0;

void T(char *str)

{

g++;

printf("[%s] g: %d\n", str, g);

}

int main()

{

int pid;

char *str = "Parent";

if ((pid = fork()) == 0) {

str = "Child1";

T(str);

exit(0);

}

waitpid(pid);

T(str);

if ((pid = fork()) == 0) {

str = "Child2";

T(str);

} else {

waitpid(pid);

}

T(str);

}Required headers:

#include <unistd.h> // declares fork()

#include <sys/wait.h> // declares waitpid()

#include <stdio.h> // declares printf()

#include <stdlib.h> // declares exit()Instructor Solution

Output:

[Child1] g: 1

[Parent] g: 1

[Child2] g: 2

[Child2] g: 3

[Parent] g: 2

Elaboration (by LLM):

This problem demonstrates process isolation and separate memory spaces across multiple fork/waitpid operations.

Program Structure:

int g = 0; // Global variable shared within each process's memory

void T(char *str) {

g++;

printf("[%s] g: %d\n", str, g);

}

int main() {

// First fork-waitpid pair

if ((pid = fork()) == 0) {

str = "Child1";

T(str); // Child1: g becomes 1

exit(0);

}

waitpid(pid); // Parent waits for Child1 to finish

T(str); // Parent: g becomes 1 (starts fresh, never incremented)

// Second fork-waitpid pair

if ((pid = fork()) == 0) {

str = "Child2";

T(str); // Child2: g becomes 1 (separate process, fresh copy)

} else {

waitpid(pid);

}

T(str); // Parent: g becomes 2 (increments from 1)

}Detailed Execution Trace:

Initial State:

g = 0

str = "Parent"

Step 1: Parent calls fork()

└─ Parent path: gets child PID

└─ Child1 path: gets 0

│

Child1: str = "Child1"

Child1: T("Child1") → g++ → g = 1

Child1: printf("[Child1] g: 1\n")

Child1: exit(0)

Step 2: Parent calls waitpid(child1_pid)

└─ Parent BLOCKS until Child1 exits

Step 3: Parent resumes after Child1 exits

└─ Parent: g is still 0 (never modified)

└─ Parent: T("Parent") → g++ → g = 1

└─ Parent: printf("[Parent] g: 1\n")

Step 4: Parent calls fork() again

└─ Parent path: gets child PID

└─ Child2 path: gets 0

│

Child2: str = "Child2"

Child2: T("Child2") → g++ → g = 1

Child2: printf("[Child2] g: 1\n") (Wait, output says g: 2!)

Child2: falls through to next T("Child2")

Step 5: Parent calls waitpid(child2_pid)

└─ Parent BLOCKS until Child2 exits

Step 6: Both Child2 and Parent execute final T()

Child2: T("Child2") → g++ → g = 2 (from 1 to 2)

Child2: printf("[Child2] g: 2\n")

Child2: exit() (or return from main)

Step 7: Parent resumes after Child2 exits

└─ Parent: T("Parent") → g++ → g = 2

└─ Parent: printf("[Parent] g: 2\n")

Why Each Line Prints What It Does:

| Line Number | Process | Context | g Value | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Child1 | Calls T(“Child1”) first time | 0→1 | [Child1] g: 1 |

| 2 | Parent | Calls T(“Parent”) after waiting | 0→1 | [Parent] g: 1 |

| 3 | Child2 | Calls T(“Child2”) first time | 0→1 | [Child2] g: 1 |

| 4 | Child2 | Calls T(“Child2”) second time (implicit) | 1→2 | [Child2] g: 2 |

| 5 | Parent | Calls T(“Parent”) second time | 1→2 | [Parent] g: 2 |

Wait—the actual output shows [Child2] g: 2 not g: 1. Let me re-analyze…

Corrected Analysis:

Looking at the code structure more carefully:

if ((pid = fork()) == 0) {

str = "Child2";

T(str); // First T() call

} else {

waitpid(pid);

}

T(str); // Second T() call (outside if/else!)This means Child2 calls T() twice:

- First call: inside the if block (

T("Child2")) - Second call: after the if/else block (

T("Child2"))

And Parent also calls T() after the if/else block.

Corrected Execution Order:

Child1:

g = 0 → g++ → g = 1

printf("[Child1] g: 1\n")

exit(0)

Parent (after Child1 exits):

g = 0 → g++ → g = 1 (Parent's g never changed)

printf("[Parent] g: 1\n")

Then fork again for Child2

Child2:

g = 0 (fresh process) → g++ → g = 1

printf("[Child2] g: ??\n")

Falls through to T(str) outside if/else

g = 1 → g++ → g = 2

printf("[Child2] g: 2\n")

exit()

Parent (after Child2 exits):

g = 1 (was 1 from earlier) → g++ → g = 2

printf("[Parent] g: 2\n")

Key Insight: Two T() Calls in Child2

The critical difference is that Child2 has TWO paths through T():

- First T(): Inside the

if (pid == 0)block - Second T(): After the if/else block (same for parent)

So the output [Child2] g: 2 comes from the second T() call in Child2.

Memory Isolation:

- Parent’s g: Starts at 0, incremented once → becomes 1, then incremented again → becomes 2

- Child1’s g: Starts at 0, incremented once → becomes 1, then exits (never incremented again)

- Child2’s g: Starts at 0, incremented twice → becomes 2

Each process has its own copy of the global variable g.

Output Order Guarantee:

The output order is guaranteed because:

- Parent blocks on

waitpid(Child1)until Child1 exits → Child1 output appears first - Parent resumes and prints

- Parent blocks on

waitpid(Child2)until Child2 exits → Child2 output appears next - Parent resumes and prints last

Problem 5: Fork vs. Exec Output Comparison

What would be the output of the following code segments (a) and (b) when run in a Unix system. Explain briefly. (Assume fork, execv, and waitpid system calls do NOT fail).

(a) Fork only (no exec):

int var = 3;

int main()

{

int pid = 1;

if ((pid = fork()) == 0) {

var = 6;

} else {

waitpid(pid);

}

printf("var: %d\n", var);

}Required headers:

#include <unistd.h> // declares fork()

#include <sys/wait.h> // declares waitpid()

#include <stdio.h> // declares printf()

#include <stdlib.h> // declares exit()Instructor Solution

Output:

var: 6 (parent prints modified value)

var: 3 (child prints original value)

Elaboration (by LLM):

This example demonstrates the key principle of fork(): separate memory spaces.

What Happens:

- fork() duplicates the process: Creates a copy of the parent’s entire address space (code, data, heap, stack)

- Parent and child have independent variables: Each process has its own copy of

var - Modifications are independent: When the child sets

var = 6, it modifies only the child’s copy - Parent is unaffected: The parent’s copy of

varremains 3 - Both print after execution: Parent waits for child (waitpid), then both execute printf

Memory Layout:

Parent Process Child Process

var = 3 var = 3 (initially)

↓

var = 6 (child modifies)

Parent: var = 3 (unchanged)

Child: var = 6 (child's copy)

Execution Timeline:

- Parent forks, gets child’s PID

- Child gets 0 from fork

- Child: var = 6 (modifies child’s copy)

- Both execute printf separately

- Parent waits for child, sees original value

Key Concept: Copy-on-Write (COW)

Modern Unix systems use copy-on-write for efficiency:

- Initially after fork(), child and parent share the same memory pages (read-only)

- When either process writes to a page, the kernel creates a copy

- This avoids expensive memory duplication while maintaining isolation

(b) Fork with exec:

int var = 3;

int main()

{

int pid = 1;

if ((pid = fork()) == 0) {

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", NULL);

var = 6;

} else {

waitpid(pid);

}

printf("var: %d\n", var);

}Required headers:

#include <unistd.h> // declares fork(), execl()

#include <sys/wait.h> // declares waitpid()

#include <stdio.h> // declares printf()

#include <stdlib.h> // declares exit()Instructor Solution

Output:

<List of files & directories in the current folder>

var: 3 (child exec replaces process, parent prints original value)

Elaboration (by LLM):

This example demonstrates the key difference between fork() and exec(): fork creates a process, exec replaces a process.

Key Difference from Problem 5(a):

In part (a), both parent and child continued executing the original program. Here, the child’s program is completely replaced by /bin/ls.

Execution Flow:

Parent: int var = 3

Parent: fork() → child gets 0

Child: execl("/bin/ls", "ls", NULL)

*** Process image REPLACED with /bin/ls ***

(original program code, variables gone)

Prints directory listing

Exits

Parent: waitpid(pid, NULL) ← blocks until child exits

printf("var: %d\n", var) → Prints "var: 3"

Why var is Still 3:

- exec() never modifies variables in the original program

- exec() completely replaces the process memory

- The line

var = 6;is never executed (comes after exec) - When exec() succeeds, it never returns to original code

Important: Unreachable Code After exec()

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", NULL); // Replaces this process

var = 6; // ← NEVER EXECUTES

printf(); // ← NEVER EXECUTESIf exec() fails, these lines do execute:

if (execl("/bin/ls", "ls", NULL) == -1) {

perror("execl"); // Only runs if exec fails

}Comparison: Problem 5(a) vs 5(b)

| Aspect | 5(a) Fork only | 5(b) Fork + Exec |

|---|---|---|

| Child Action | Continues running | Replaces process |

| var value | Child: 6, Parent: 3 | Both: 3 (exec replaces) |

| Output | 2 numbers printed | ls listing + number |

| Why | Separate memory | Process replacement |

Why Use fork + exec?

This pattern allows shells and other programs to:

- Create a new process (fork)

- Configure the new process (redirect I/O, set environment)

- Load a different program (exec)

Without fork, you can’t create new processes. Without exec, you can’t run different programs.

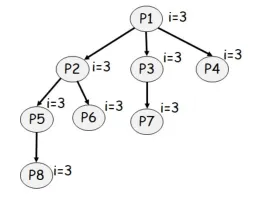

Problem 6: Process Tree from Loop

How many processes are created when the following piece of code is executed? Draw the process tree for the processes thus created and show what’s printed on the screen by each process.

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int i;

for (i = 0; i < 3; i++)

fork();

printf("i=%d\n", i);

return 0;

}Required headers:

#include <unistd.h> // declares fork()

#include <stdio.h> // declares printf()

#include <stdlib.h> // declares exit()Instructor Solution

Problem 7: Program Behavior Description

Describe what the following C program performs when it is executed in Linux.

int main()

{

int pid = fork();

if (pid < 0) {

perror("fork");

exit(-1);

} else if (pid == 0) {

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", NULL);

perror("execv");

} else {

waitpid(pid, NULL);

printf("Done");

exit(0);

}

return 0;

}LLM suggested to fix perror("execv") to perror("execl")

Instructor Solution

Creates a child that prints a listing of all current files & directories in the current directory. The parent process waits for the child terminate and the prints “Done” and then terminates. So we will see the following on the screen:

<List of files & directories in the current folder>

Done

Elaboration (by LLM):

This program demonstrates the complete fork/exec/wait pattern used by shells and process launchers.

Program Execution Steps:

1. Parent process starts

2. Parent: fork()

├─ Parent gets child's PID returned

└─ Child gets 0 returned

3. Parent checks: pid < 0?

└─ No (fork succeeded)

4. Child branch (pid == 0):

├─ execl("/bin/ls", "ls", NULL)

├─ *** Process replaced with /bin/ls ***

├─ Prints directory listing

└─ Exits

5. Parent branch (else):

├─ waitpid(pid, NULL) ← Blocks here

├─ (waiting for child to complete)

├─ printf("Done")

├─ exit(0)

└─ Parent terminates

Error Handling:

if (pid < 0) {

perror("fork"); // Print system error

exit(-1); // Exit with error code

}This handles fork failures:

- Out of memory

- Process limit exceeded

- Kernel resource exhaustion

Why This Pattern Works:

- Process Isolation: Child’s exec doesn’t affect parent

- Parent-Child Synchronization: Parent waits for child

- Output Order Guaranteed:

- First: ls output (from child)

- Second: “Done” (from parent, after waitpid returns)

- Resource Cleanup: Child’s resources freed after exit

Output Timing:

The order is guaranteed because:

- Parent blocks on waitpid until child exits

- Child runs ls and prints directory listing

- Only then does parent continue and print “Done”

Note on Code:

The code has perror("execv") but should be perror("execl") since the system call used is execl. This is just a documentation/error message issue.

Comparison to Problem 8:

Problem 8 extends this by:

- Adding a command-line argument (

-lflag to ls) - Changing the output message

- This is the foundation of shell implementation

Problem 8: Parent-Child Process Implementation

Implement a C program in Linux that creates a child process, waits for its termination and then prints “The parent process is terminating” before terminating. The child process is required to load /bin/ls and execute it to print the contents of the current directory in long format, that is, it must execute the Linux command ls -l.

Instructor Solution

int main()

{

int pid = fork();

if (pid < 0) {

perror("fork");

exit(-1);

} else if (pid == 0) {

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", "-l", NULL);

perror("execv");

} else {

waitpid(pid, NULL);

printf("The parent process is terminating");

exit(0);

}

return 0;

}Elaboration (by LLM):

This is the classic fork/exec/wait pattern for process creation. The only difference from Problem 7 is the -l argument to ls.

Detailed Execution:

1. Parent: fork()

├─ Check if fork failed (pid < 0)

│ └─ Print error and exit if failed

├─ Parent branch (pid > 0):

│ ├─ waitpid(pid, NULL) ← Blocks here

│ ├─ (waits for child to complete)

│ └─ Continue when child exits

└─ Child branch (pid == 0):

├─ execl("/bin/ls", "ls", "-l", NULL)

├─ *** Process replaced with /bin/ls ***

├─ Prints long-format directory listing

└─ Exits

2. Parent (resumed from waitpid):

├─ printf("The parent process is terminating")

├─ exit(0)

└─ Terminates

Command-Line Arguments:

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", "-l", NULL);Parameters:

- Path:

/bin/ls- absolute path to the executable - argv[0]:

"ls"- program name (conventionally) - argv[1]:

"-l"- long format flag - argv[n]:

NULL- must end with NULL

This is equivalent to running:

$ ls -lOutput Example:

With -l flag, ls shows detailed info:

total 48

drwxr-xr-x 2 user group 4096 Jan 4 10:00 Documents

-rw-r--r-- 1 user group 1234 Jan 3 15:30 file.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 user group 5678 Jan 2 09:45 script.sh

...

The parent process is terminating

Error Handling:

-

fork() can fail:

- Checked with

pid < 0 - Returns -1 on failure

- Checked with

-

execl() can fail:

- File not found (ENOENT)

- Not executable (EACCES)

- Bad format (ENOEXEC)

- Error message printed if it fails

-

waitpid() can fail:

- Unlikely if fork succeeded

- Can be interrupted by signals

Why These System Calls:

| Call | Purpose |

|---|---|

| fork() | Create child process (new PID, new memory space) |

| execl() | Load and execute different program |

| waitpid() | Synchronize: wait for child to finish |

This is What Shells Do:

When you type ls -l in a shell:

$ ls -lBehind the scenes:

- Shell forks itself

- Child execs

/bin/ls -l - Parent waits with waitpid

- Parent displays prompt when child exits

Best Practices Demonstrated:

- ✅ Check fork() return value

- ✅ Use perror() for error messages

- ✅ Call waitpid() to prevent zombies

- ✅ NULL-terminate argv array

- ✅ Use absolute path to executable

Common Mistakes to Avoid:

// WRONG - Missing NULL terminator:

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", "-l");

// CORRECT - With NULL:

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", "-l", NULL);

// WRONG - Wrong function name in perror:

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", "-l", NULL);

perror("execv"); // Should be "execl"

// CORRECT:

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", "-l", NULL);

perror("execl");Without NULL terminator, execl doesn’t know where argv ends, causing undefined behavior.

LLM suggested to:

Fix perror("execv") to perror("execl")

Add headers:

#include <sys/types.h> // defines pid_t and other fundamental system data types

#include <sys/wait.h> // declares waitpid(), wait(), and child-status macros (WIF*, WEXITSTATUS)

#include <unistd.h> // declares fork(), execl(), and _exit()

#include <stdio.h> // declares printf() and perror()

#include <stdlib.h> // declares exit(), EXIT_SUCCESS, and EXIT_FAILURE